On 17th August, 1940, six brave men from the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal team sadly lost their lives trying to defuse a bomb in the fields around Nantwich in Cheshire, and this is their story………

Thanks to the work and knowledge of local historian, Andrew Lamberton, I was made aware of the story of the six bomb disposal men that were killed in the early stages of WW2, close to the town of Nantwich. Working closely with Andrew and with the help of photographs taken at the time, we have been able to piece together what happened on that fateful day in August 1940.

Initially it was thought that the bomb that killed the men was one of five German bombs that were dropped on the same night, in the area around Nantwich, from what was believed to be one single German Bomber, most likely a Heinkel He III, returning from a bombing raid in Liverpool, although so far, we have been unable to verify this.

(Heinkel He III)

There is also supporting evidence that the bombs could equally have fallen from separate raids over several nights, again this is something that we have so far been unable to prove conclusively. From oral testimony at the time and further investigations, we know that the five bombs that fell in the Nantwich area were located at the following sites; one fell in a field at Mile House Farm, in Worleston; another landed at Windy Arbour in Nantwich; one bomb was located at Brook Farm, Alvaston; a fourth landed behind 8, Birchin Lane in Nantwich; and a fifth bomb fell behind Dairy House Farm, Colleys Lane, Willaston.

To give some background context to the War situation at the time that these bombs fell in and around Nantwich, we have to remember that this would have been at the height of ‘The Battle of Britain’, which took place over the skies of Britain during June-September 1940. The Luftwaffe air power consisted of a total of 2,669 aircraft of which, 1,015 were bombers. Up against this, our own RAF had 704 single-engined fighters, Spitfires and Hurricanes, alongside 440 bombers. By early August 1940, German raids had become focused on British airfields and aircraft industry. On 1 August the Germans issued ‘First Directive 17’ “for the conduct of air and sea warfare against England” (Great Britain). Of course, by this time, the skies around Southern Britain were already accustomed to aerial battles. On 13 August the German Luftwaffe launched an attack on Britain of approximately 1500 aircraft and this was swiftly followed on 15 August by an even larger attack of 1,270 fighters and 520 bombers, which was directed towards British air bases and their support infrastructure including air defence targets, aircraft factories, repair depots and anti-aircraft sites, all of which would have included many targets in Cheshire, most notably the Rolls Royce factory in Crewe.

(Known German Luftwaffe Flight Paths)

The bombs that fell in and around Nantwich were thought to be a German SC250 (250kg) type bomb, which Germany used throughout the war and one that they previously used in the Spanish civil war. The German Luftwaffe used two types of bombs, the SC like the ones that we believe fell around Nantwich and a SD type. The SD used a thicker metal for fragmentation, these were used against soft targets, where shrapnel was more important than blast, so against people on a battle field or vehicles. The SC were a thin-walled bomb designed for use against hard targets where a ‘blast effect’ would be more useful, for example, houses, buildings etc.

(Types of German Bombs used during WW2)

Between July and December 1940 the Luftwaffe dropped over 27,000 tons of bombs on British cities, killing over 23,000 British civilians and injuring a further 39,000 people, which is shown in the tables below.

It’s difficult to ascertain with complete certainty what the original bomb targets were, but looking at the trajectory line of the bombs that fell, it does add weight to the fact that the bombs that were dropped were possibly from planes on their way back from a raid on Liverpool. If you plot all the bomb locations on a map, which has been drawn by my friend Andrew Lamberton, it shows a clear line and what would be a natural flight path for a plane returning from Liverpool to Germany. See the OS maps below.

(OS Map Showing the Five Bomb Sites and the Map below showing the possible trajectory line)

However, there always has to be a balance of evidence when you cannot prove something with absolutely certainty. At the time, it’s also worth noting that there were gun emplacements in the fields behind Dairy House Farm on Colleys Lane and of course the Rolls Royce factory was just down the road at Crewe, which was where the Merlin Engines were manufactured. The Merlin Engines were essential to the defence of the UK and were most closely associated with the Spitfire and Hurricane, although the majority of the production run was for the four-engine Avro Lancaster Bomber. To add further context, Crewe was at the time was and still is today, a central hub in the Railway Network for the whole of the UK and many troops, munitions and other equipment associated with the war effort, would have been transported around the UK at the time, making Crewe a very realistic target for the enemy. As some of the bombs that fell in and around the Nantwich area had failed to detonate, members of The Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal Squad were called in to defuse them. In this particular case, all were attached to the 10th Battalion Kings Regiment (Liverpool).

Royal Engineer Bomb Disposal began in September 1939, when it was decided by the War Office that the Royal Engineers (RE) would provide temporary bomb disposal teams until the Home Office could recruit and train special ARP teams to do so. At the time that the men died, it was still the early stages of the war and harsh lessons were being learnt by the bomb disposal teams on a daily basis. The first teams consisted of an NCO and two sappers, and they were required to dig down to the bombs and blow them in situ. The first bombs to be dropped on the UK were in the Orkneys in October 1939, while the first unexploded bombs fell on the Shetlands in November 1939. The Formation Order of May 1940 formally handed responsibility for Bomb disposal to the Royal Engineers and created 25 bomb disposal sections, soon increased to 134. Despite almost non-existent equipment and little training, the sections learnt fast. In June 1940, just 20 unexploded bombs were dealt with. This rose to 100 in July, 300 in August and over 3000 in September. By this point, the Bomb Disposal section had increased in number and been organised into 25 Bomb Disposal Companies. Between September 1940 and July 1941, over 24,000 bombs were made safe and removed.

On arrival at a bomb site, the bomb disposal teams would work on bombs that were categorised due to their importance, see the list below;

A UXB affecting something vital to the war effort would need to be dealt with first. Bombs were therefore divided into categories: –

A1 – Immediate disposal essential. Detonation of the bomb in situ cannot be accepted on any terms. (Meaning men could not wait until a possible delayed action bomb had gone off – They would have to recover it no matter the risks.)

A2 – Immediate disposal essential. Bomb may, if the situation demands, be detonated in situ.

B – Rapid disposal urgent, but less urgent than A.

C – Not necessarily calling for immediate action.

D – May be dealt with as convenient. (For example, UXBs in open countryside.)

However, depending on how busy the unit was, Category D bombs might be dealt with straight away, though would probably be left a couple of days as a precaution in case they were delayed action bombs, which could go off up to 96 hours after being dropped.

At the time the men would have had only the most basic training and used the simplest of tools such as a screwdriver, pliers and a stethoscope. On arrival on site, a bomb disposal section would dig down to the bomb, using whatever materials were available, often timber and doors from bomb damaged houses, corrugated iron, in fact anything they could lay their hands on. Timber was in short supply at the start of the war due to many of the supply ships being torpedoed by the enemy. The fact that these bombs landed on farmland would have meant that there would have been some materials available to the men to use. When they got down to the fuse, the officer would more often than not have to use a hammer and cold chisel to loosen the locking ring, and withdraw the fuse by hand, many officers would tie a piece of string round the fuse boss enabling him to pull out the fuse from relative safety. The bomb was then usually rolled over and then loaded onto a lorry for disposal. It should be noted that in the early days a ‘lorry’ would not have been an army issue, but a requisitioned vehicle, in this instance most likely a farm vehicle. The terrain would have also have been wet and they would have made use of local fire brigade pumps to ensure the pits remained dry. At the time the local Fire Brigades and Bomb Disposal teams worked closely together during the war effort.

It was whilst attempting to defuse one of these unexploded bombs that tragedy struck. On Saturday 17 August 1940, a team of Royal Engineer’s from the Bomb Disposal Section, attached to the 10th Battalion Kings Regiment (Liverpool), were attempting to defuse an unexploded bomb (UXB) at Brook Farm in Alvaston when it exploded prematurely, killing four members of the squad outright and seriously wounding two others. The four men that were tragically killed were Sappers Albert Fearon, Michael Lambert, George Lucas and Harold Thompson. The injured men were taken immediately to the local Nantwich Cottage Hospital and the following day, 18th August 1940, Sapper John Perrins succumbed to his injuries and one day later, Sergeant Edward Greengrass also died, on 19th August 1940. It’s now also thought that as well as the six men that died, a further seven men from the Bomb Disposal team were injured after the bomb exploded. The postcard below shows how the Hospital would have looked at the time and the picture below shows that hardly much has changed over the passage of time.

Sergeant Edward Greengrass was buried at Wandsworth Cemetery in London, Sapper Albert Fearon was buried at Byker and Heaton Cemetery in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Sapper Michael Lambert at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green in London, Sapper George Lucas was buried in Philips Park Cemetery, Greater Manchester, Sapper John Perrins was buried in All Saints Churchyard Stand, Whitfield, Bury and Sapper Harold Thompson was buried in Hornchurch Cemetery in Hornchurch Essex.

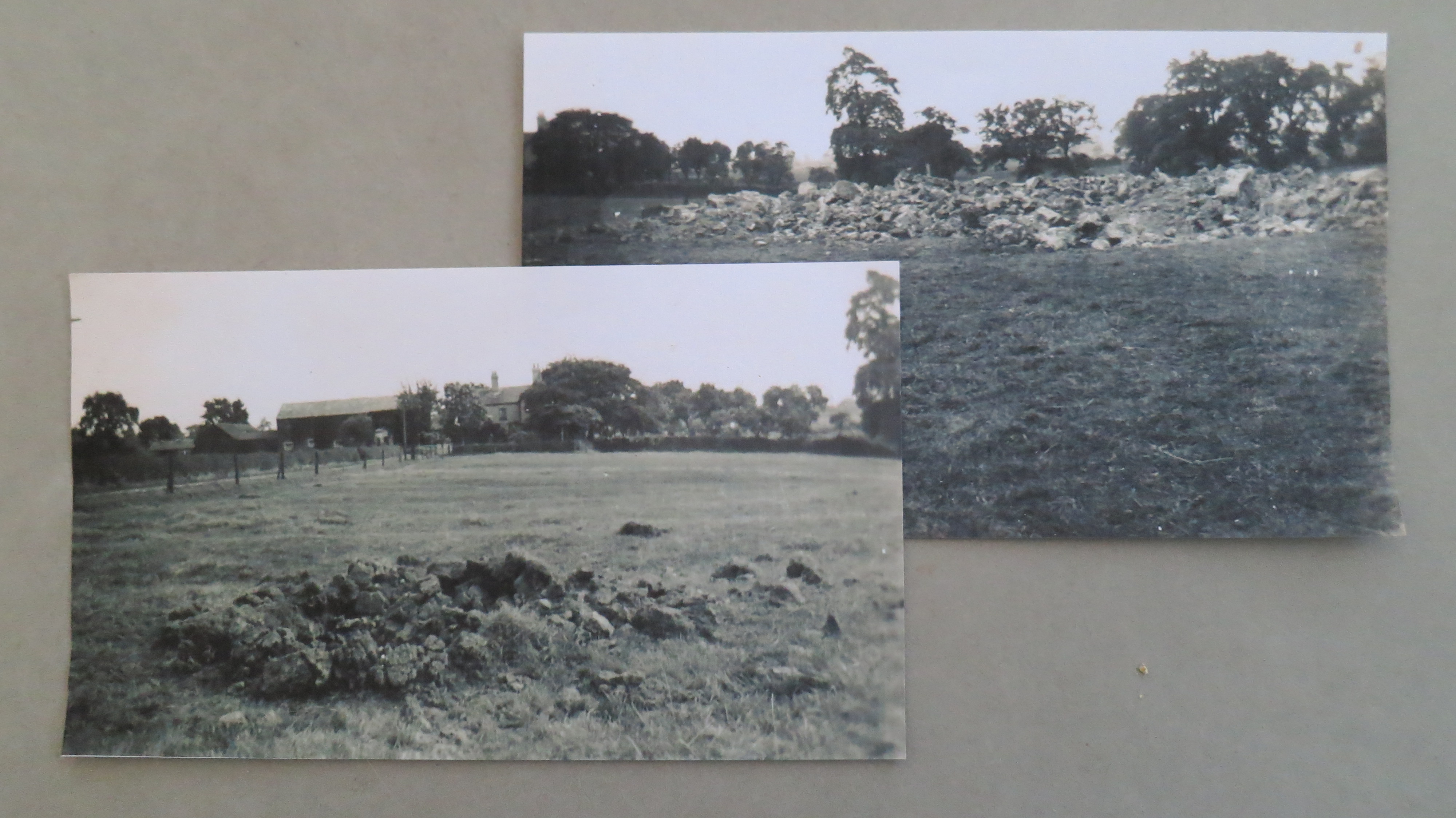

With the aid of photographs that were taken at the time and numerous site visits, from our extensive research, we now believe that we have been able to identify the site of the bomb that tragically killed the six men. The picture below shows the initial impact crater from the bomb that landed at Brook Farm, the farm itself can clearly be seen in the background.

(Brook Farm)

Whether this was a delayed timer device or whether it was during the excavation phase of the recovery, is uncertain, but the bomb exploded with devastating effect, killing the six men from the bomb disposal unit. The crater from the bomb after it prematurely exploded can be seen below.

By overlaying the two pictures above, we can see from the tree lines and the lay of the land, the original site and crater and the aftermath after the bomb exploded.

Below is a picture taken in 2024 of the same property and we have tried to replicate these positions in the pictures below, to try to identify as best we can, the exact spot where these brave men lost their lives.

(Brook Farm April 2024)

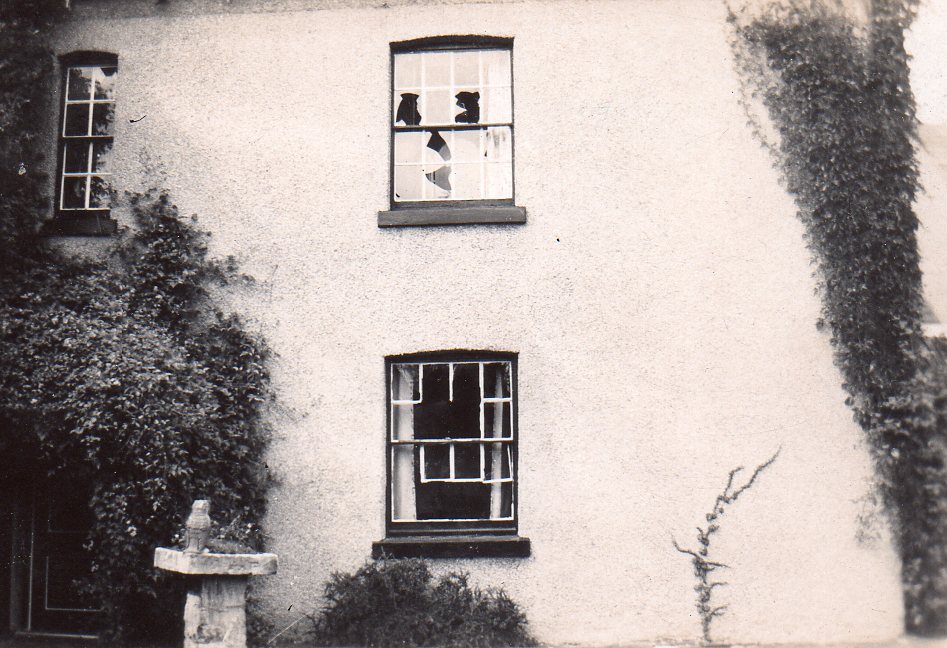

The extensive damage caused by the bomb that exploded prematurely at Brook Farm can be clearly seen in the pictures taken at the time. In the first picture we can clearly see the damage caused to the front of the house and in the second picture we can see how the blast wave ripped through the house, taking further windows out on the other side of the house.

(Brook Farm August 1940)

The extensive damage on two sides of Brook Farm is also a clear indication that the bomb exploded unexpectedly. In situations like this, being within close proximity of a property, if there was any risk of an explosion, residents would be told to open all the windows to try and avoid the pressure wave taking out the glass, which has clearly happened here. The pictures below, again taken recently by me, show that little has changed at Brook Farm in the intervening years. I have tried to replicate the original pictures in the pictures that I have taken.

(Brook Farm April 2024)

Although there is no supporting evidence so far, to suggest that all these bombs fell on the same night, the other areas that were bombed around Nantwich were also investigated and researched.

The bomb that fell at Dairy House Farm was successfully defused by the bomb disposal team and is marked as number 5 on the OS map above and it was here that the image below was taken of the bomb disposal team after the successful defusing of the bomb. Initially I thought that the six men who sadly died were part of this group of men. However extensive research into the lives of the six men that died have revealed photographs which clearly shows that they were not part of the team in this photograph.

(The Bomb Disposal Team at Dairy House Farm Auguste 1940)

Again, myself and Andrew carried out extensive research into the fields behind where Dairy House Farm would have been and we were also assisted by another local resident, Roger Birchall who had initially identified what was thought to be the bomb crater site. Roger is the son of George Edward Birchall, who owned Dairy House Farm in Colleys Lane, from 1908-1955.

(Roger Birchall and Andrew Lamberton at Dairy House Farm April 2024 – The crater site clearly visible in the background)

(Dairy Farm Crater Site April 2024)

There is however one anomaly that doesn’t quite ‘fit’ with our original theory and flight path, and that is the bomb discovered and successfully defused, behind 8, Birchin Lane in Nantwich, which is shown as position 4 in the map above. The site of Birchin Lane does not quite fit the trajectory line of the other bombs. The picture below shows a gentleman named Sam Barlow who was a member of the Home Guard at the time and lived at 8, Birchin Lane, proudly standing with one foot on the bomb, he is certainly a braver man than me! The second picture shows A.R.P Head Warden, William Day also pictured here behind the house in Birchin Lane, bravely standing next to the defused bomb.

(Home Guard Member Sam Barlow pictured here in Birchin Lane, Nantwich)

(A.R.P Head Warden, William Day)

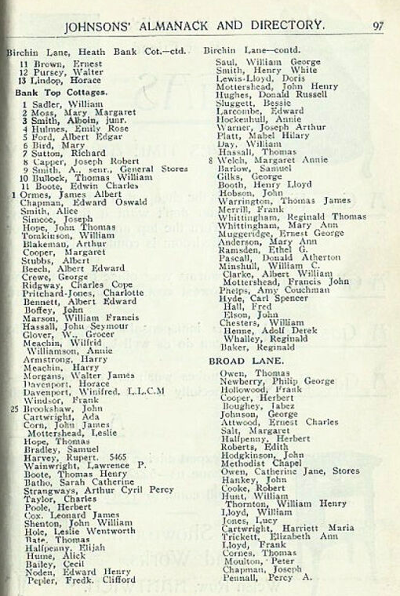

A copy of the 1939 Johnsons Almanack shows clearly that Sam Barlow and William Day were clearly neighbours at the time in Birchin Lane in Nantwich and would most certainly have known each other.

(1939 Johnsons Almanack)

A site visit into the fields behind 8, Birchin Lane revealed the most likely area that this bomb was discovered, you can see the field taken from both the house side and also looking back towards the houses. Although I can’t pinpoint the exact spot, I can safely say that the bomb was recovered from this field.

(The Field behind 8, Birchin Lane taken from both perspectives in April 2024)

Sam Barlow’s son, John recounted the following story about his father’s exploits during the war

“This is a picture of my father, Sam Barlow, standing beside a bomb which had been recovered from the middle of a field behind our house in Birchin Lane, Nantwich, Cheshire. Luckily for all of us it hadn’t exploded. Below the area in Cheshire where we lived was running sand and because of this the bomb disposal team took about six weeks to recover the bomb. I can’t remember the exact date but it must have been fairly early on in the war when I was four or five. German bombers had been targeting Liverpool and Crewe, which was just about four miles away. I clearly remember the Air Raid Warden cautiously climbing the air raid shelter steps and looking towards the field. We were in our neighbour’s shelter along with others from nearby houses. He decided that we would have to leave our houses immediately, so we set off to stay with my mother’s sister who lived in Willaston just a couple of miles away. My father was in such a hurry that he had to ask permission to go back into the house to collect his false teeth!

On another occasion I clearly remember a German bomber flying over our house towards Crewe. It was a Sunday afternoon and obviously broad daylight. The pilot turned slightly north and then we saw a puff of smoke over the Rolls Royce factory away in the distance. He had dropped a bomb on it, but as far as I can remember no serious damage was done to the manufacturing part of the factory. One night, a German plane was heard. It was flying low over the main road that runs from Nantwich to Crewe. We heard later that when the plane reached Wistaston the pilot started to machine gun the ground below.

At other times during the war we had evacuated children staying with us. One, a girl, came from Liverpool, and another, a boy called Norman, came from Wallasey. He didn’t like Nantwich. He said that all the planes flying over reminded him of home. He didn’t feel safe.

My father wasn’t fit for war duties so he joined the Home Guard. The stories we heard easily matched the escapades of the men in the TV series “Dad’s Army”. They got lost on training exercises; my father nearly shot the colonel and the story of the rapid descent down the stairs in the Old Town Hall in Nantwich by one of my father’s colleagues after a bomb had dropped and exploded a couple of miles away was hilarious. He reached the ground and was flat on his face alongside my father before the blast blew out the window of the Maypole shop nearby.“

Unfortunately, no photographs exist at the site of the first two bomb sites, at Mile House Farm, in Worleston and Windy Arbour in Nantwich. Although we know the areas, we are therefore unable to say with any kind of certainty where these two bombs landed.

The story lay dormant for many years after the war until the local branch of the Royal Engineers at Crewe decided that it was time to mark the occasion with a permanent memorial. Appeals were made in the press to try to trace the families of the six men who were killed, but only one family member was traced at the time.

Alvaston Hall provided the location for the memorial, as it was the nearest suitable site to the field where the explosion occurred. On Sunday, October 7, 2012, an unveiling and dedication ceremony of the memorial took place at Alvaston Hall in front of military personnel, friends and families. One of those present was the nephew of one of the six men killed. The Mayor of Cheshire East, Councillor George M. Walton, welcomed those present and later unveiled the memorial stone. The memorial stone was dedicated by the Mayor’s Chaplain, the Rev Canon Michael Walters in a short service and The Last Post and Reveille were sounded by a bugler from the Co-operative Band.

With special thanks to my good friend Andrew Lamberton for all his help and in particular his local knowledge, without which, I would have struggled to tell this story.

Thanks also to author Chris Ransted for his help with understanding the role played by the bomb disposal teams during WW2 and his book ‘Bomb Disposal in WWII (National Archives)’ proved to be an invaluable resource, see the link below.

Bomb Disposal in WWII (National Archives)

Bringing the story up to date to the present time, I decided that it would be a fitting tribute to trace and tell the stories of all six of these brave men who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country and I will be writing and remembering all of the six men in a series of forthcoming blogs.

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2024 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

Thanks, Paul, for another excellent article. Your dedication to perform correct research is evident here. The crew’s members were all brave men and I’m amazed at how much they accomplished with such scant training and tools. Also loved the Dad’s Army references – that is one fabulous show!

Question – how did you approach the current farm owners to take photos? Did you know them prior to starting research or was it an interesting conversation starting with, “Hello, you don’t know me but I’d like to …” 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Lynne for your kind words. With regards approaching current farm and land owners it was just a question of politely knocking and a case of “did you know……” In two of the locations they did have some prior knowledge which made the conversation that much easier and they were very keen to hear the story once I explained what happened

LikeLike

That’s great to hear you had a cooperative set of interviewees! I envy you – so much history in your country and many stories yet to be unearthed. Keep up the good work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lynne, in fact some of the photos that I took which never made the final version were taken from one of the residents upstairs bedroom windows 😁

LikeLike

A fascinating story passed to me by my daughter. I was born at Brook Farm in 1949 and lived there until 1973. My brother, Patrick, was born there in 1942 and lived there until he retired from farming. I was told about the bomb and the deaths. The story I got was that the bomber had been attacking Crewe Works as the farm was in direct line with them. There was, and may still be, shrapnel imbedded in the wall of the house after the bomb went off. On the initial photo of the crater you can see a window in the side of the house between the trees. The shrapnel was mainly just to left of that window. As well as the broken windows some of the plaster from the ceilings in the downstairs rooms was also brought down. You could see the repairs, not very well done, all the time I lived there. The photos that you have of the damage, I still have as well – somewhere!

My father was in the Home Guard as a lot of farmers were during the war so may have known the two gentlemen from Birchin Lane.

I now live in Kendal and have not been back to Brook Farm for many years but still have a great interest in the place and a love of the area.

Peter Grange

15.06.24

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing with me your memories of your time at Brook Farm and it’s amazing that my story has somehow managed to find you and bring back all these memories! I believe that you might know Andrew Lamberton? It was Andrew that first told me about the bombing and he mentioned your name on numerous occasions whilst I was visiting the farm and researching the story. I’m not sure if you went to school with Andrew? I believe he knew your family quite well at the time. Now that you have mentioned the shrapnel imbedded in the wall means that I will have to go and visit the farm again and have a close look to see if I can spot any damage. Thank you again for reaching out and sharing with me your memeories

LikeLike

I am not sure I know or at least remember Andrew Lamberton. My memory for names is not as good as it was! The house used to be pebble dashed but the recent photos look like it has been rendered in which case the shrapnel might have gone.

If you do go back please let me know if you have any success.

LikeLike

Yes of course, if I manage to find something I will be sure to take some pictures and let you know. Thanks again so much for sharing with me all this new information best wishes Paul

LikeLike