Another iconic picture and another innocent life captured forever behind a lens, but who was the poor little girl whose life was perpetually framed in this picture and what was her story?

The little girl in the picture was Adelaide Springett and she was captured in this beautiful photograph by Horace Warner who captioned the photograph “Adelaide Springett In All Her Best Clothes” and she was to become, what I can only describe as the ‘cover girl’ to highlight the plight of the poor during Victorian Britain.

(Adelaide Springett 1901)

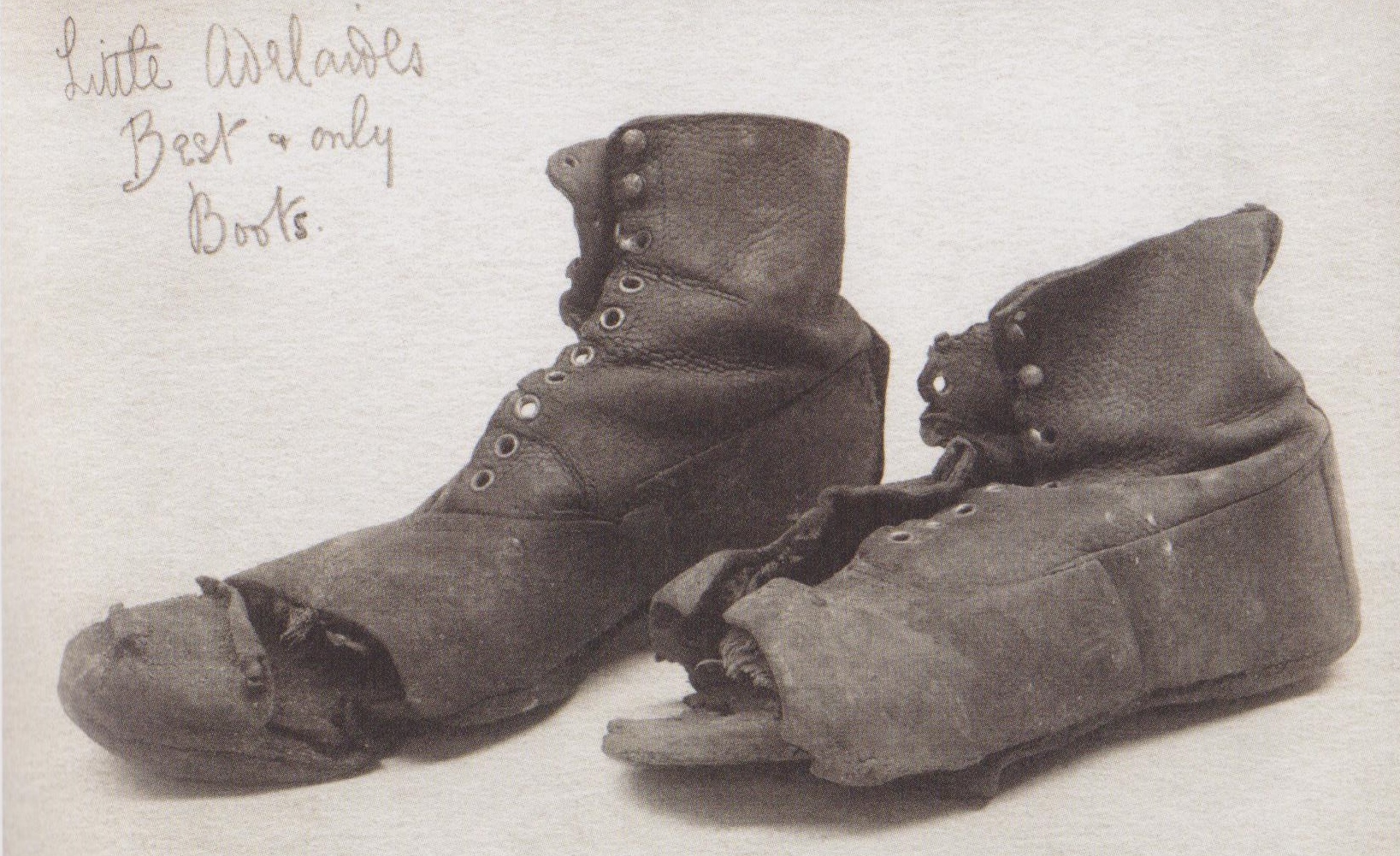

When the photograph was taken, so the story goes, poor Adelaide was so ashamed of her boots that she took them off for the photo. The photographer who took the picture in 1901, Horace Warner’s daughter Ruth, recalled her father’s picture captioned “Little Adelaide’s best and only boots”, upon the living room wall during her childhood, alongside portraits some of the other Nippers, which served as a reminder of those less fortunate than she and her sister Gwen.

(Adelaide’s Boots)

The Gentleman who captured the picture of Adelaide was a man named Horace Warner, who was a Sunday School Teacher at the Bedford Institute Quaker Mission in East London. Horace took a series of photographs of the children to highlight the poverty-stricken conditions of the poor children in East London at the time. To help raise funds for these children, Horace wrote short stories, to accompany the photographs and these stories were published by the Bedford Institute in the form of fund-raising leaflets in 1912. Assuming the fictional alter-ego of the fairy ‘Silverwing’ the story he paints was the grim reality of life for those families and goes some way to show why the life expectancy of their children was so short. A life that was to reflect the life of poor Adelaide Springett.

The night was getting late and silverwing must be back before dawn, but he flew along the road and alighted at the Spitalfields Market. All was still within, but outside in the gutter were a few cases of rotten oranges, and around those were gathered several children with their arms plunged elbow deep in the rotting fruit, feeling for an orange here and there that might be less rotten than the bulk within those cases. Other children were hunting amidst the market garbage for anything that might be of use at home. Nigh by, another squalid street was guarded top and bottom by the public houses, and a passage way leading into it was likewise guarded by another, so that no-one could enter into the street without passing one, and halfway down the same stood another, with its temptation of warmth and light. A little court entrance, bearing no name over it, tempted silver wing to go still further, so up the alley-way he went. This too, had its one gas lamp, beneath which a number of big boys were gambling round an inverted barrel, losing and gaining their hard-earned pence. Still another staircase in the corner of the court tempted the fairy to go. The stairs were dark and irregular and seemed to twist and turn until the first little landing was reached. A child was leaving a darkened room and silverwing slipped in. Within sat a lad of ten nursing a baby until his mother had returned with the father from hawking toys in the gutter to help pay the night’s rent and there were also two smaller brothers on the mattress behind the door. The grate lacked any fire, and the light again only from that of the chance gleam from the court gas lamp.

The story clearly describes Dorset Street and Millers Court. His photographs have appeared in many newspaper publications over the years and in 2014 Spitalfields Life Books, published Horace Warner’s ‘Spitalfields Nippers’, which contained a collection of his portraits of Victorian Children. You can read more about Horace Warner here. The copyright to the picture of Adelaide and her boots remains with ‘Spitalfields Life’ who have kindly allowed me to use these pictures to help tell Adelaide’s story.

But who was this little 8 year-old-girl captured so innocently in this iconic image and what was her story?

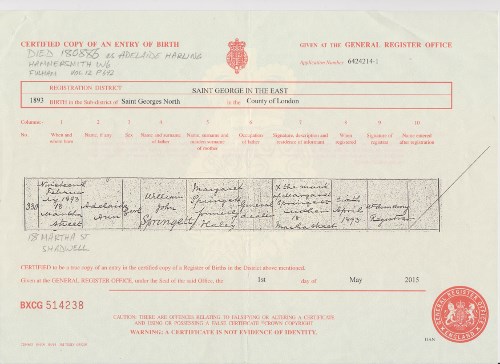

Adelaide Ann Springett was born on 19 February 1893 in the parish of St George-in-the-East, Wapping. Named after her Auntie Adelaide Springett, she was born into a family that was already fighting to survive, but little did she know what darkness and struggles lay ahead for her and her family. Her father was William John Springett, born in Marylebone in 1852 and her mother was Margaret Haley, born in St Lukes, Old Street in 1860. Adelaide’s mother Margaret was a second-generation immigrant from Ireland, her father, Patrick Haley was a general dealer who had come over as part of the migration of Irish people escaping the famine and poverty of Ireland in the pursuit of work. Around this time, the East End of London and Spitalfields in particular was a melting pot, full of a multitude of nationalities all trying to survive. It’s estimated that by 1900, over 90% of the population of Stepney were immigrants or second-generation immigrants.

(Birth Certificate for Adelaide Springett)

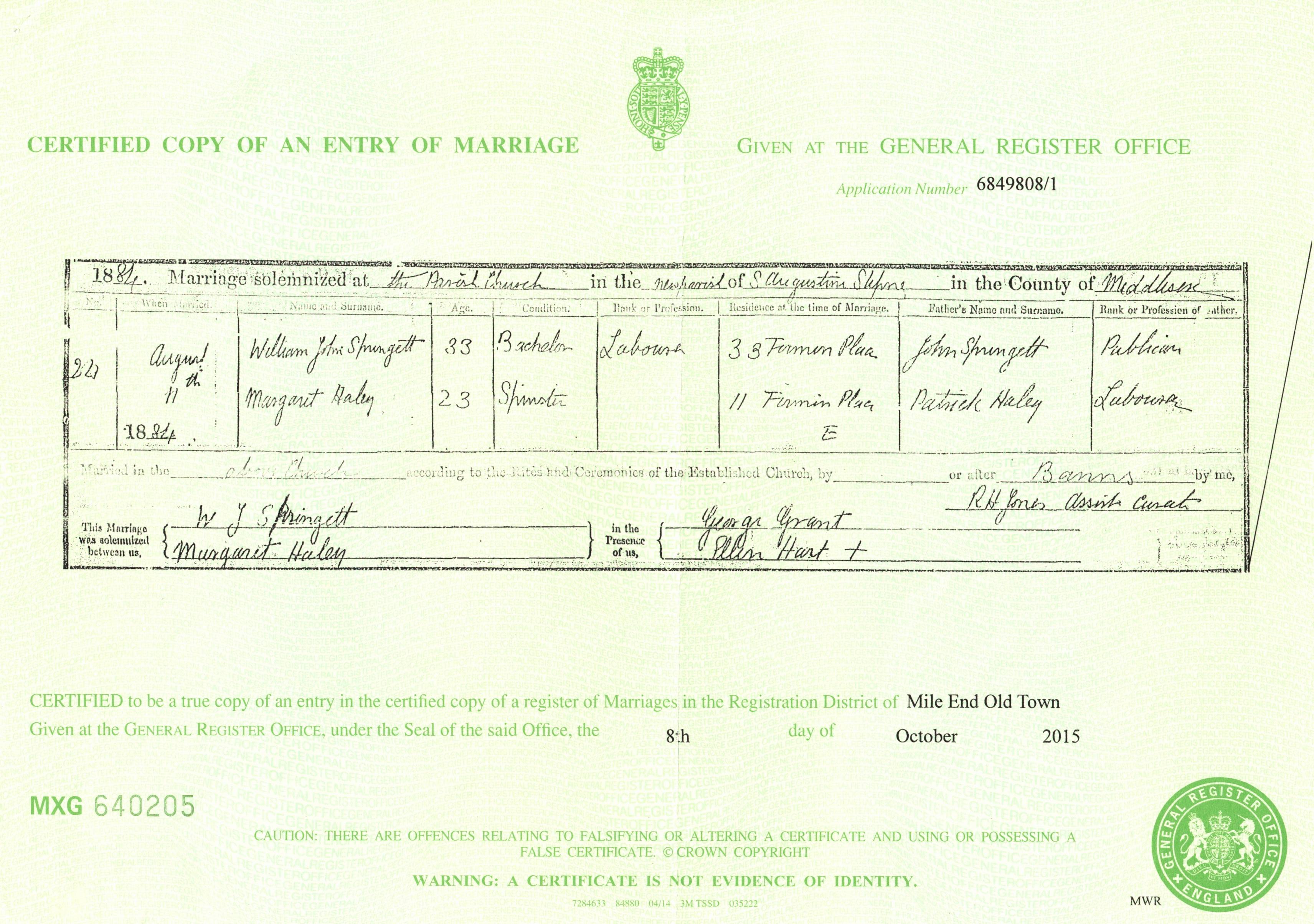

At the time of her birth Adelaide and her parents were living at 18, Martha Street in Shadwell, London and her father was recorded as a ‘general labourer’. Adelaide’s parents were married on 11 August 1884 at Saint Augustine Church, Stepney, Tower Hamlets in London. Saint Augustine’s stood in a poor district between Commercial Road and Whitechapel Road. At the time of Adelaide’s parent’s marriage, her father, William John Springett was aged 33 and living at 33, Firmin Place and her mother, Margaret Haley, aged 23, was living at 11, Firmin Place. William’s father, John Springett, was recorded as a publican and Margaret’s father, Patrick Haley, was a labourer.

(Marriage Certificate for William John Springett and Margaret Haley)

Both her parents were costermongers, although William was recorded as a labourer when he first married his wife. Costermongers or Hawkers, typically served anybody who would buy their wares, usually from a hand cart, that would have been wheeled through the narrow streets of East London. It would have been an extremely tough life, trying to scratch a living, fighting with others just to earn enough money to feed themselves each day and after that, the next thought would be where would they find a roof over their heads for the night. The Costermongers trade was not only fruit and veg, out of season trade could be toys or anything else which they could turn into a little profit. They were basically street sellers and towards the end of a days trading, the wholesalers of Spitalfield’s market would be looking to get rid of their leftover stock by selling it off cheaply to the costermongers, who in turn would hawk it round the streets and make a little profit. That was how they survived.

(A Typical Costermonger’s barrow)

(Spitalfields Market Circa 1900)

It’s here that we start to see the ‘real story’ of Adelaide’s plight unfold. Adelaide’s parents, William John Springett and Margaret Haley had a total of five children, four girls including Adelaide and one boy. However, before Adelaide was born, the young couple had tragically lost three of their children, all within just one month of each other, which might have been the catalyst that sparked the awful circumstances that were too unfold. Something that we will never be able to answer with any certainty.

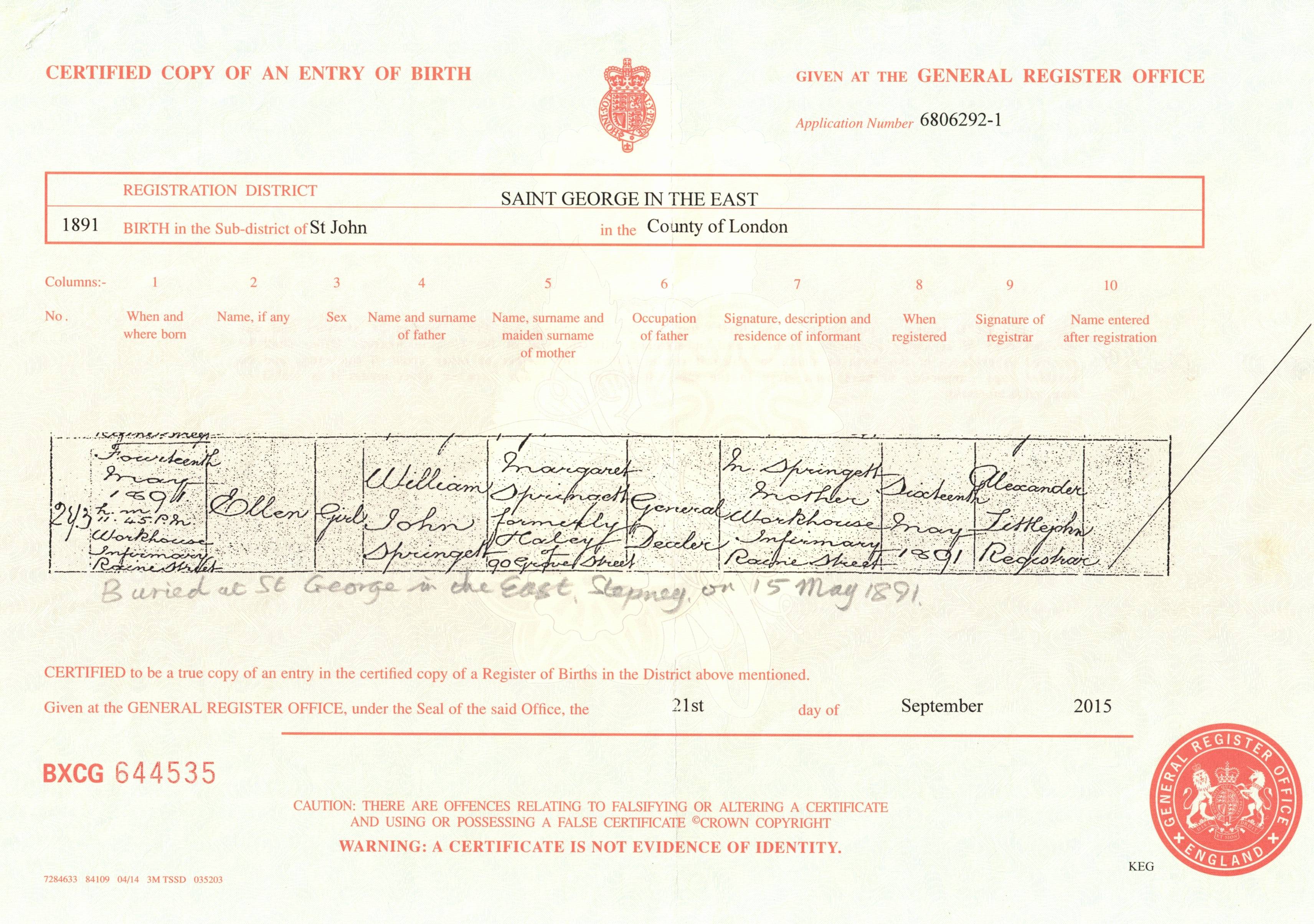

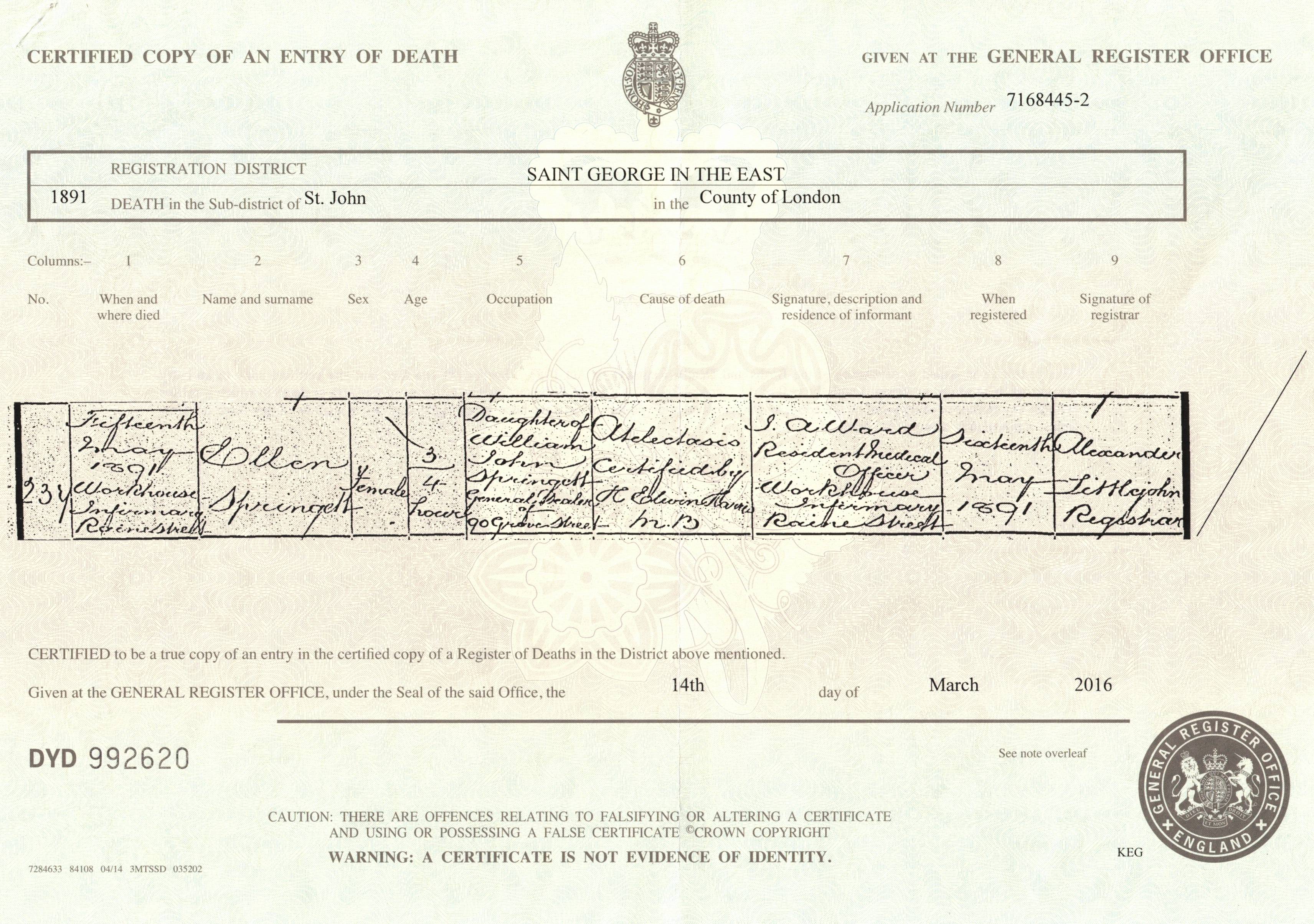

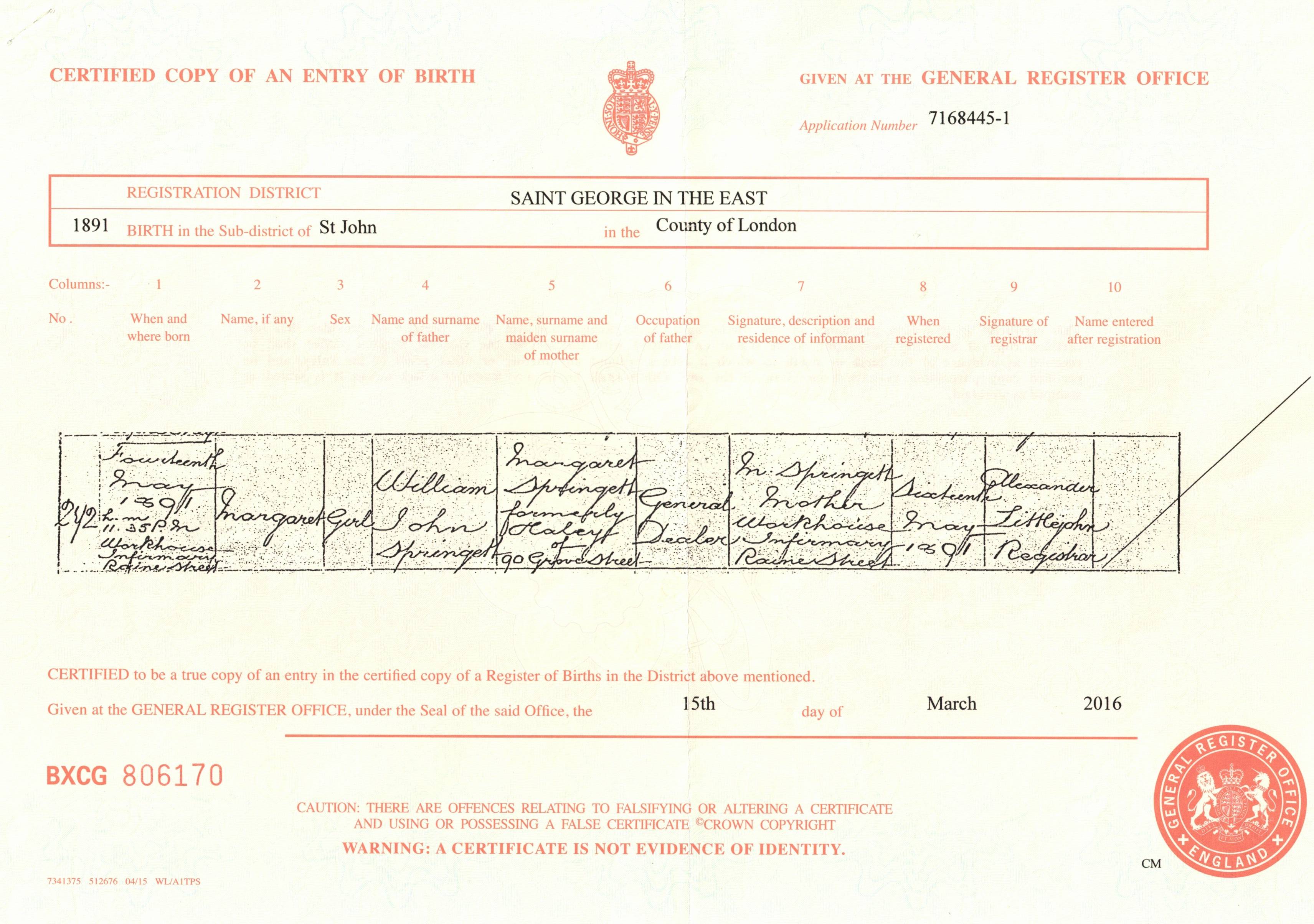

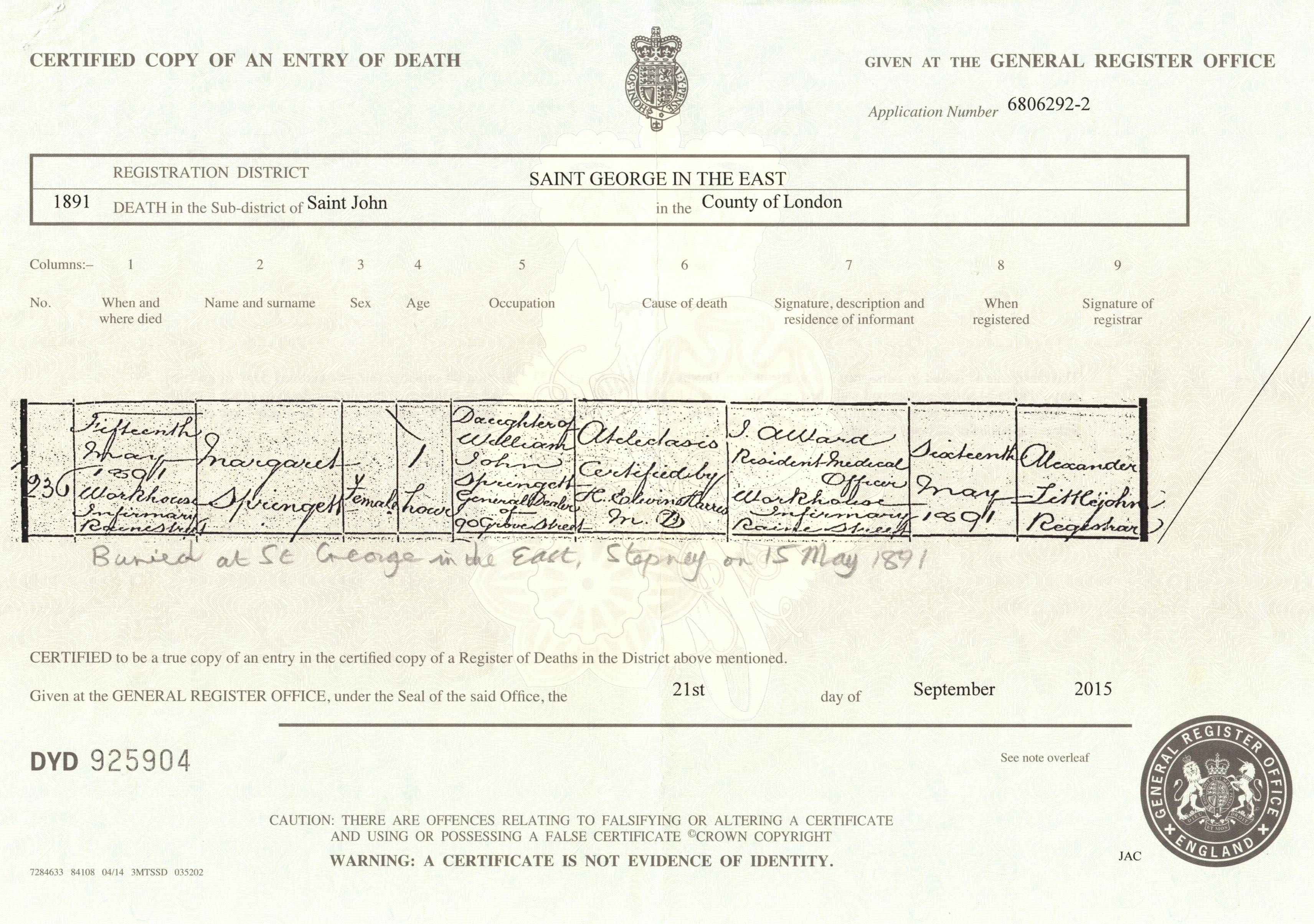

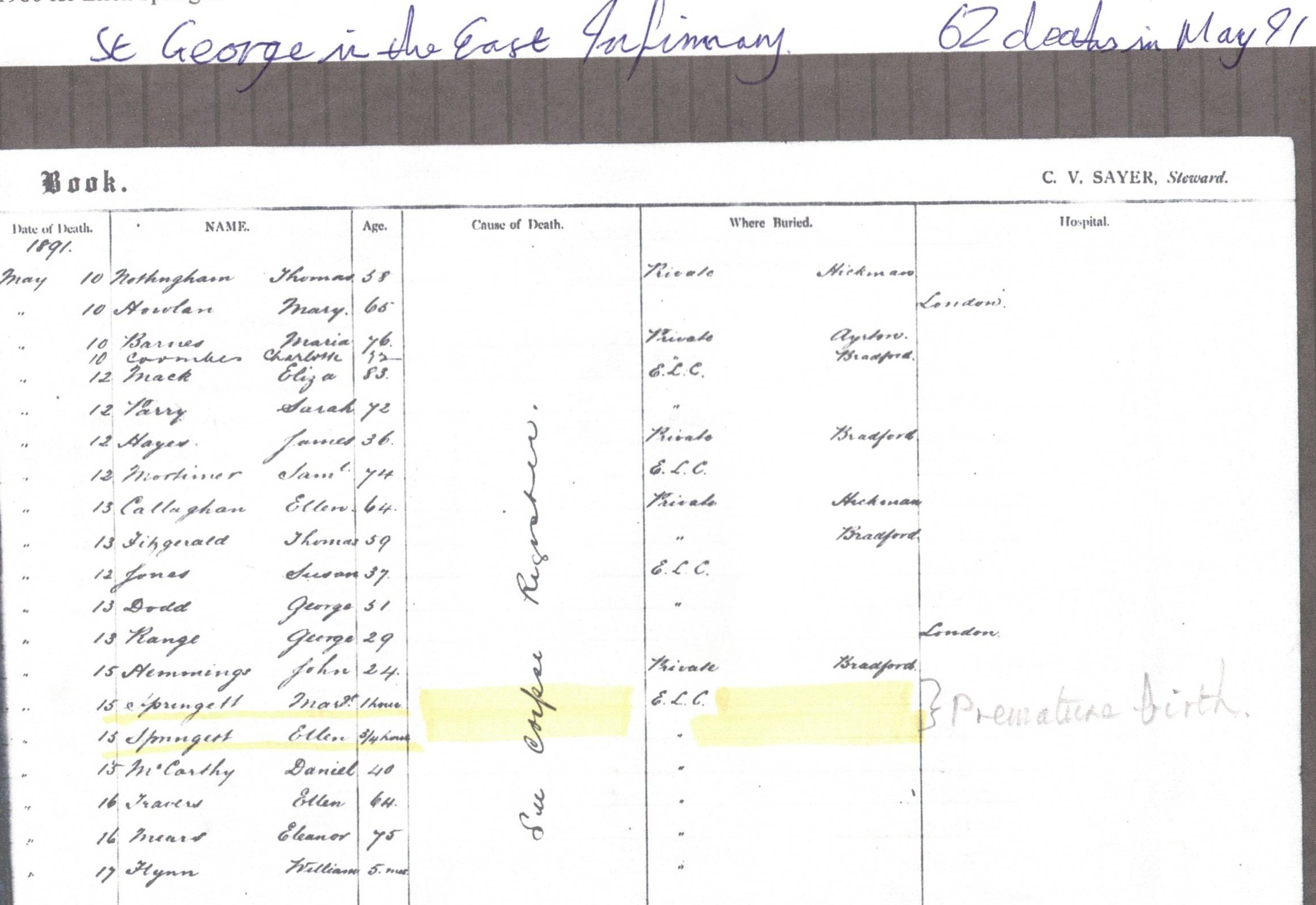

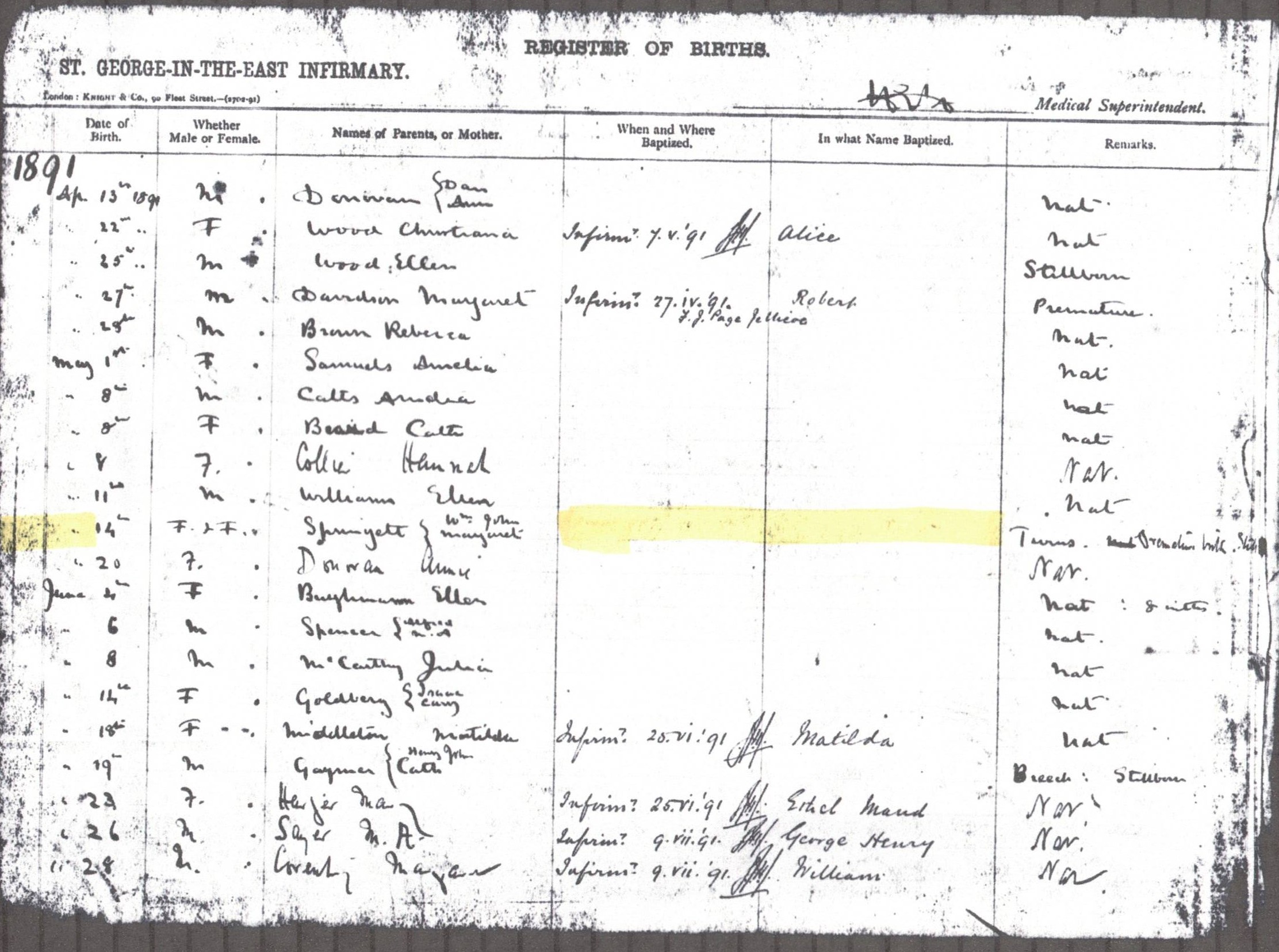

Adelaide’s twin sisters Ellen and Margaret were born prematurely on 15 May 1891, in Raines Street, Workhouse Infirmary, Wapping and they both died, within an hour of their birth, from Atelectasis. Atelectasis was a problem associated with the lungs and was most likely caused by their premature birth and the lungs not being formed fully. Ellen sadly died 45 minutes after she was born and her twin sister Margaret only survived for one hour.

(Birth Certificate for Ellen Springett)

(Death Certificate for Ellen Springett)

(Birth Certificate for Margaret Springett)

(Death Certificate Margaret Springett)

(Infirmary Records for Ellen and Margaret Springett)

(Infirmary Records for Ellen and Margaret Springett)

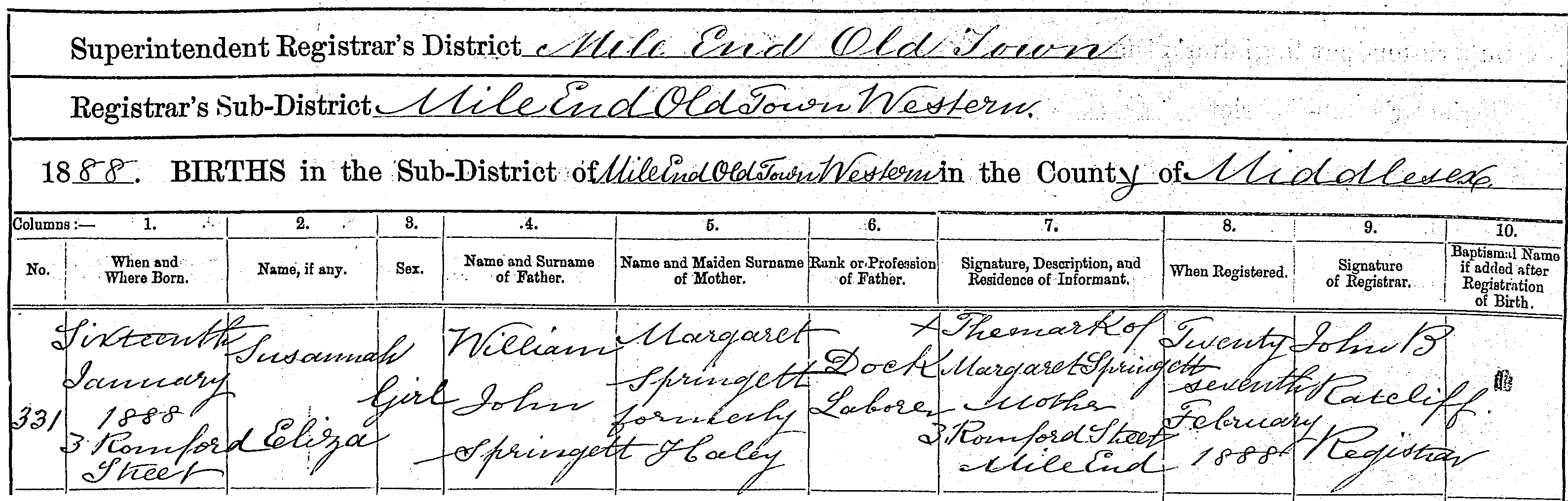

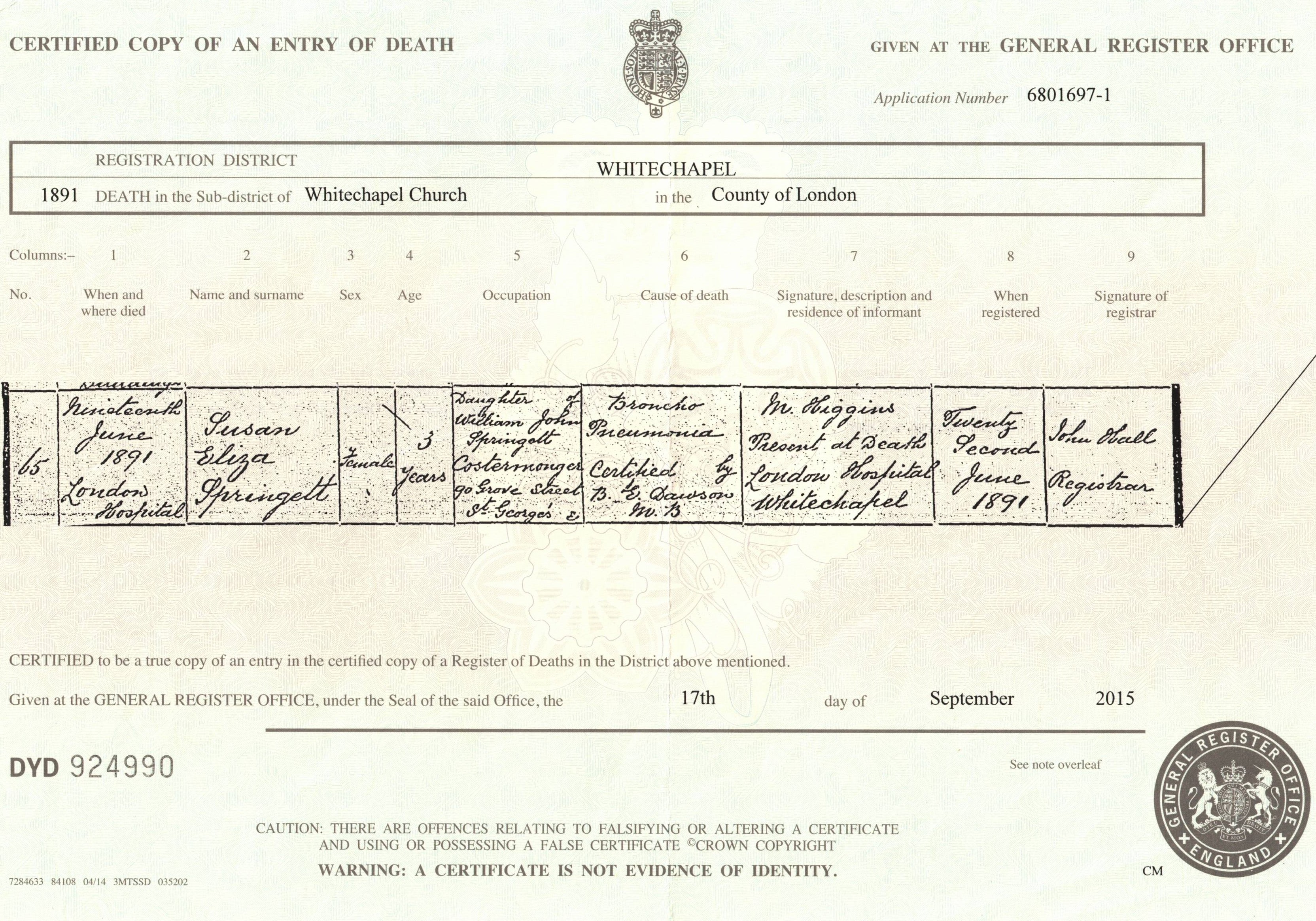

Less than one month later, Adelaide’s other sister, Susannah Eliza died on 19 Jun 1891, aged only 3, in the London Hospital, Whitechapel of Bronchial Pneumonia. Susannah Eliza was born on 16 January 1888, just three years before.

(Susannah Eliza Springett Birth Record)

(Death Certificate for Susan Eliza Springett)

Life expectancy for the poor was extremely low, if you then place these poor people in the most deprived and harshest of living conditions, then life expectancy fell even further. In 1890 in London the average life expectancy at birth was 44 compared to the national average of 46, but behind these figures lay another story. A person in the West End of London had almost twice the life expectancy of those living in the East End. At the time the average age of death in the West End was 55 and in the East End it was just 30. Childhood mortality rates were even more shocking. In the West End, 18% of children died before the age of 5, in the East End 55% of children died before the age of 5. The facts are startling enough, but behind every one of these facts is a child, a face, a person and a family that suffered immeasurable loss, just like Adelaide’s family. Adelaide’s poor mother had lost three children in the space of just four weeks. How you recover from such awful circumstances like this I don’t know. It almost feels like ‘death’ had become a part of every day life.

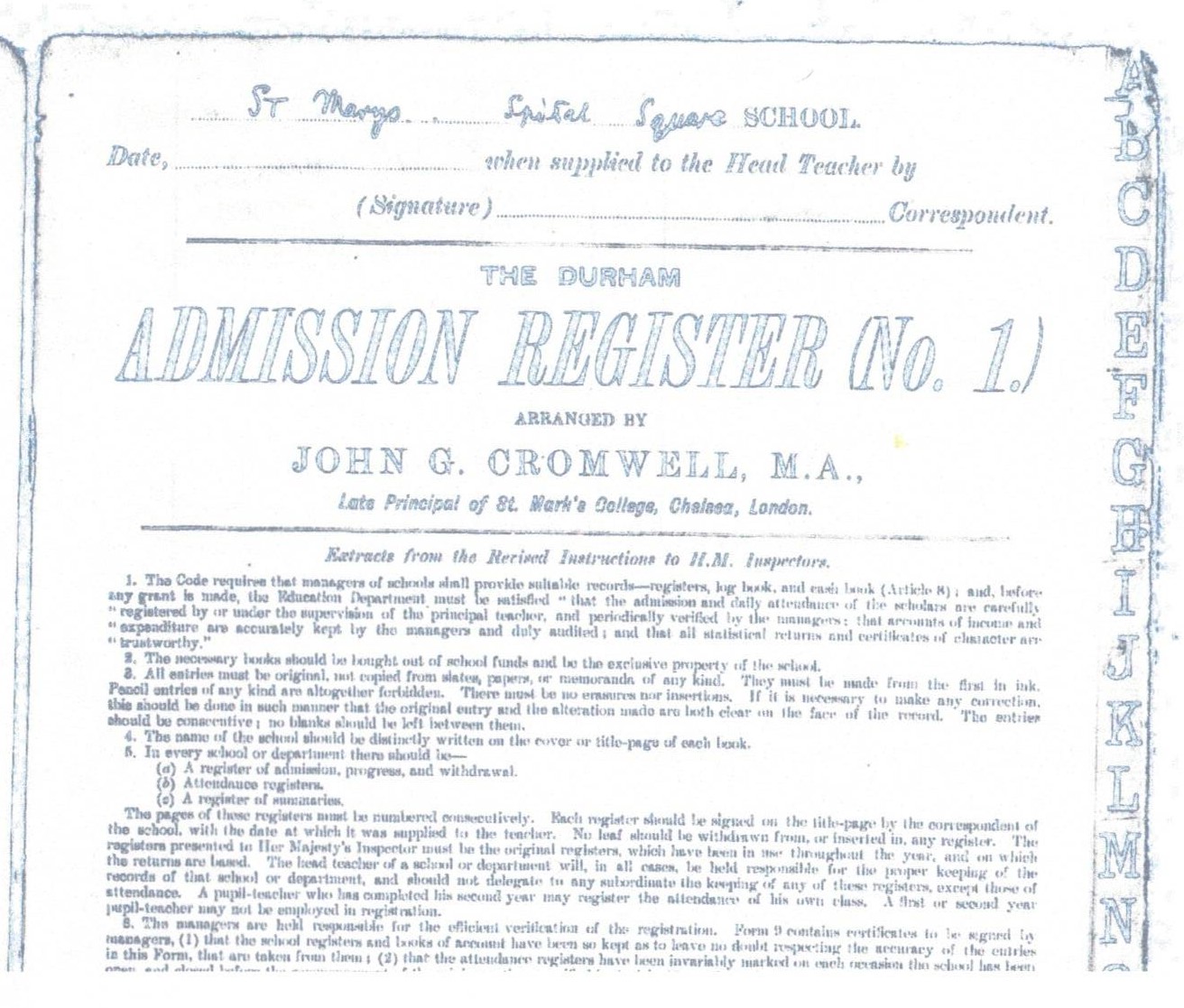

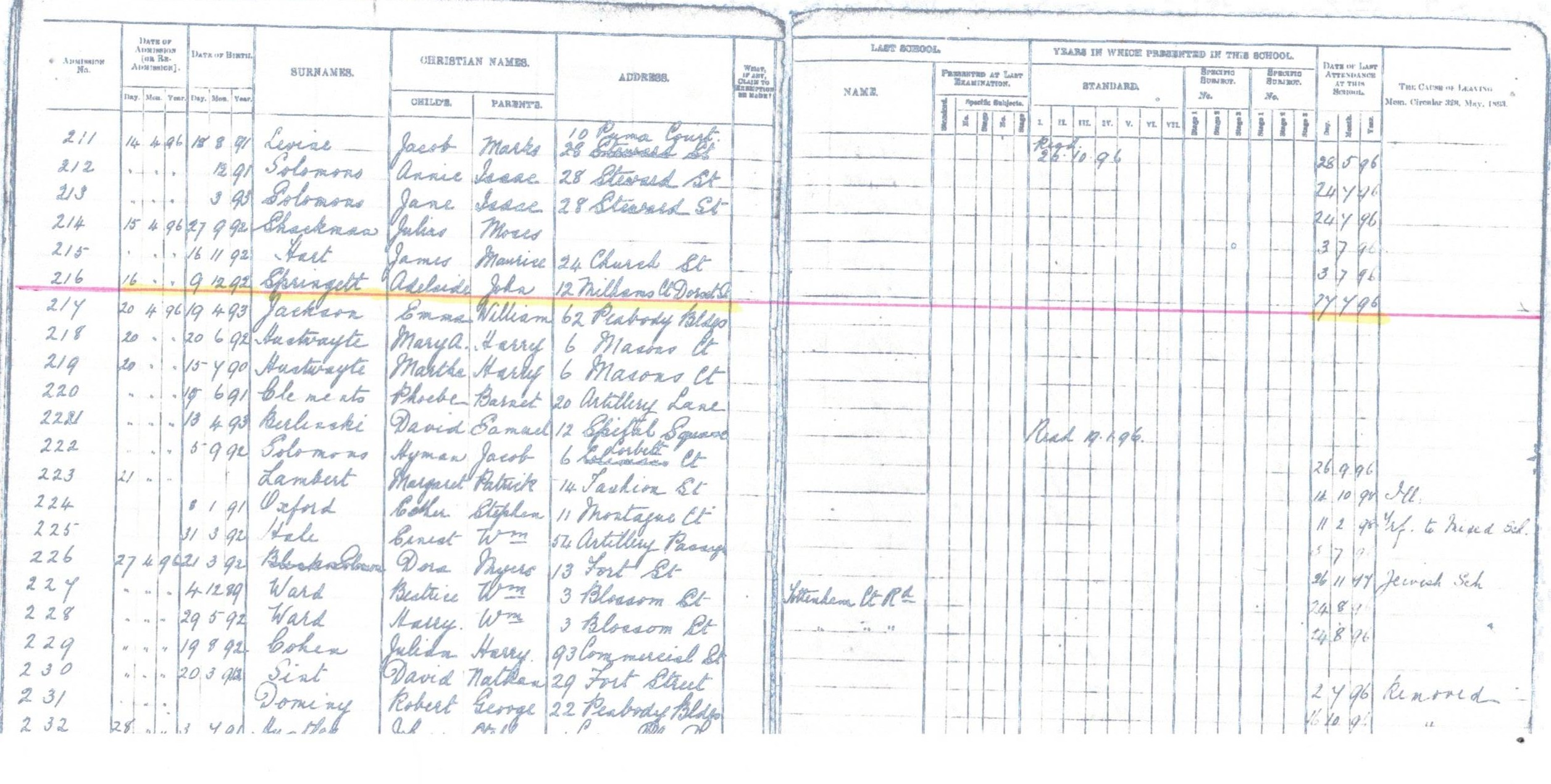

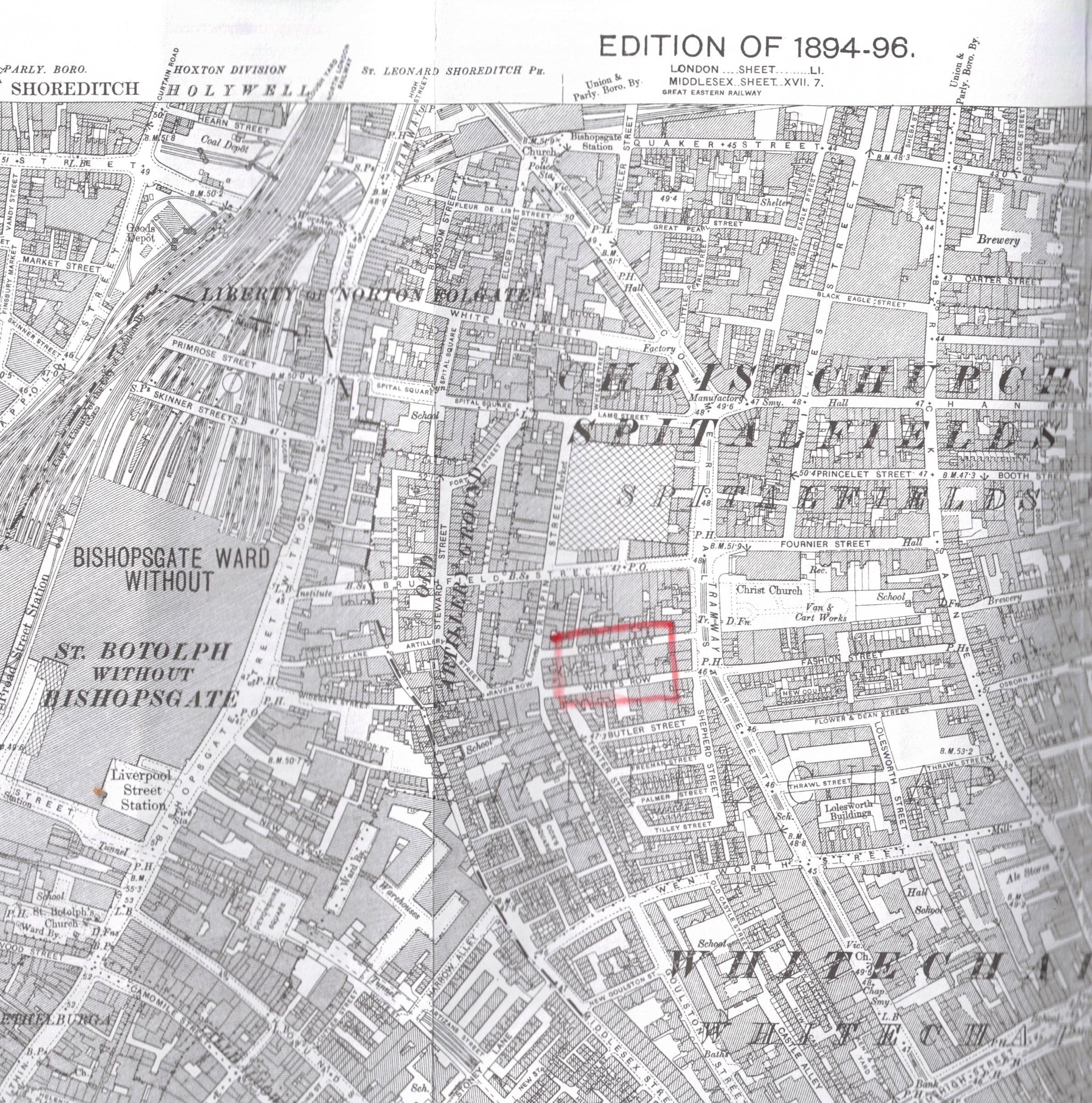

Surprisingly two school records survive for young Adelaide. She first attended St. Mary’s Roman Catholic School in Spital Square, aged just 3, on 16 April 1896. At the time of her admission, her mother put her date of birth back by 3 months, which I suspect was to get her into school early. I was initially surprised at how young Adelaide was when she attended both Roman Catholic schools and suspected that there was a reason for this? Was this an easy form of childminding perhaps, or a safe place to leave her while she was out ‘Hawking’ the streets? At the time of her admission to St. Mary’s, her address was recorded as 12 Millers Court, Dorset Street.

(School Admission Record for St. Mary’s Catholic School)

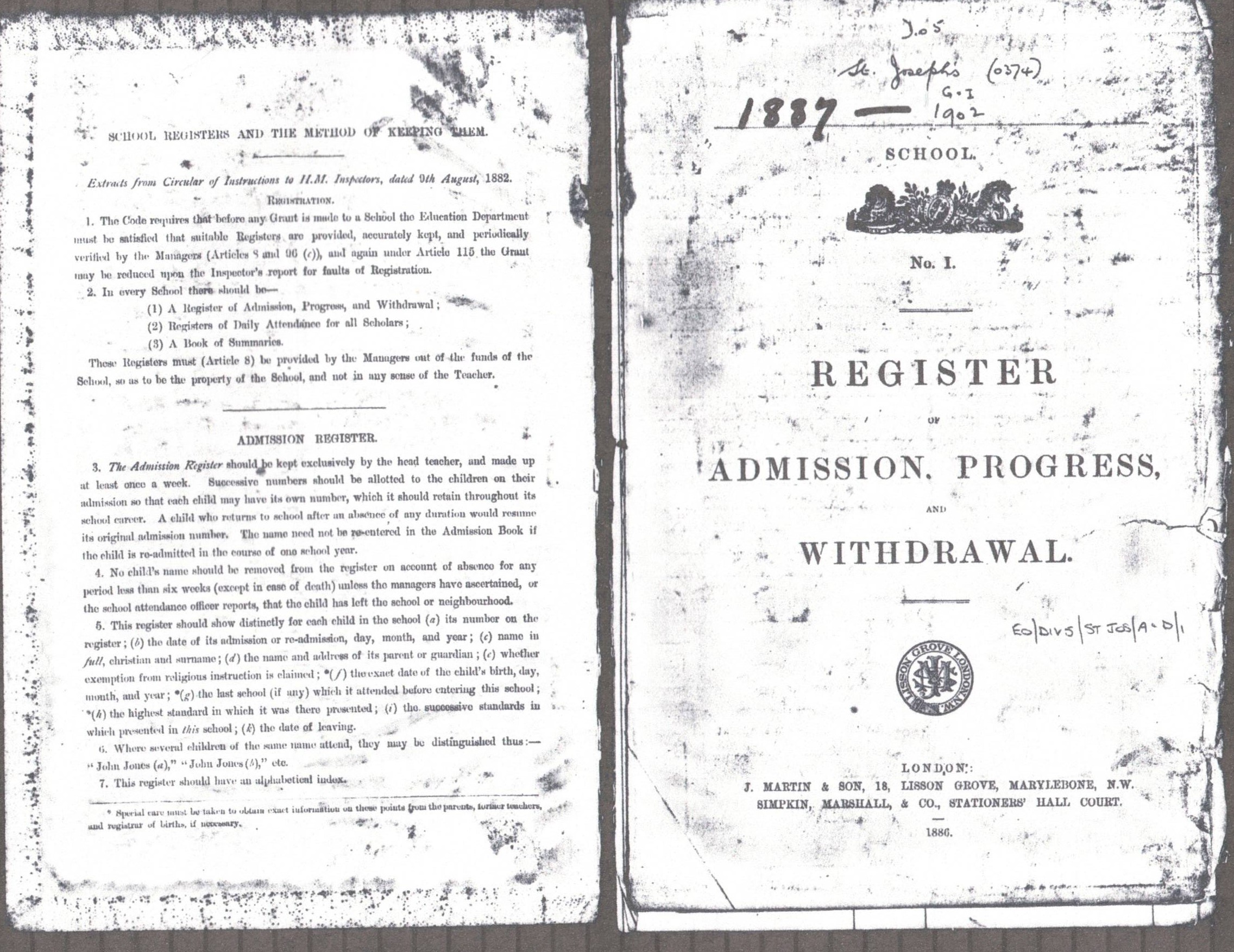

The admissions records also show that just over a year later, on 11 October 1897, she attended St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic School, her address that was given at the time was 26, Dorset Street.

(School Admission Record for St. Joseph’s Catholic School)

When I was researching Adelaide’s story, I was immediately struck by the familiar sound of the address recorded on her school admission record, of 12 Millers Court. But I was absolutely shocked when I discovered why that address sounded so familiar to me.

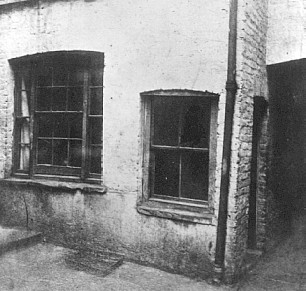

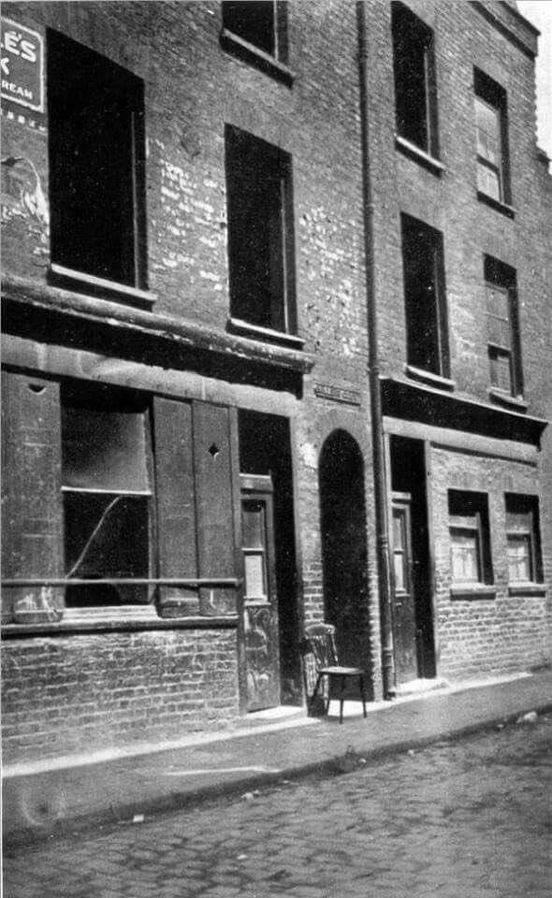

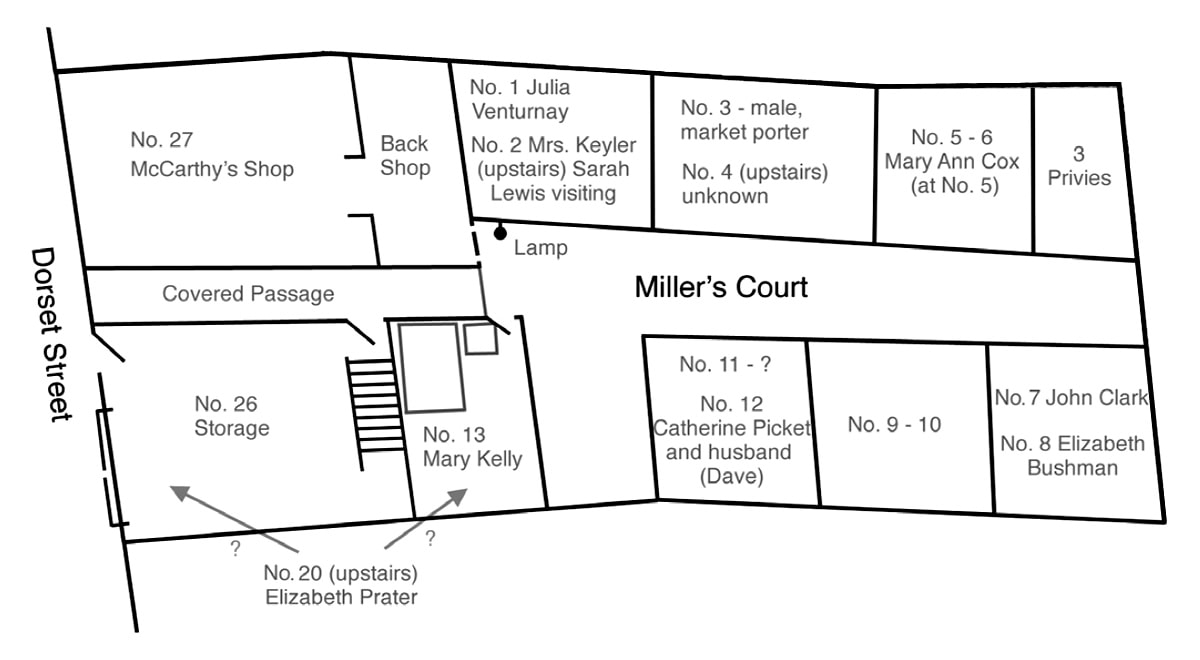

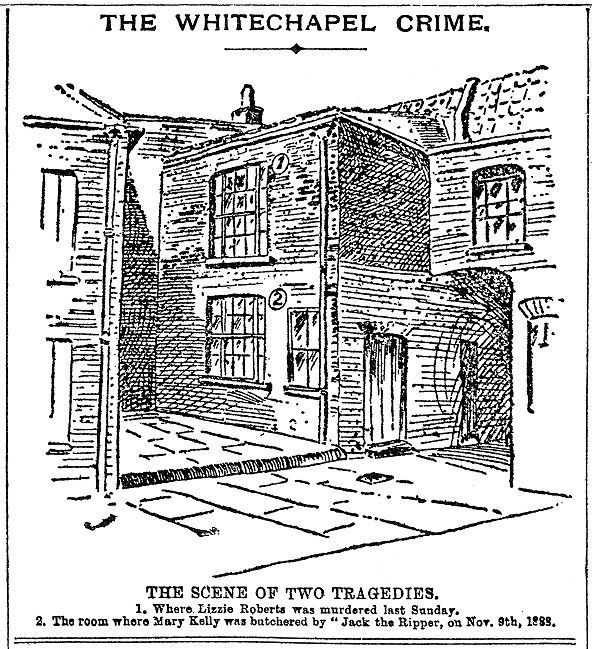

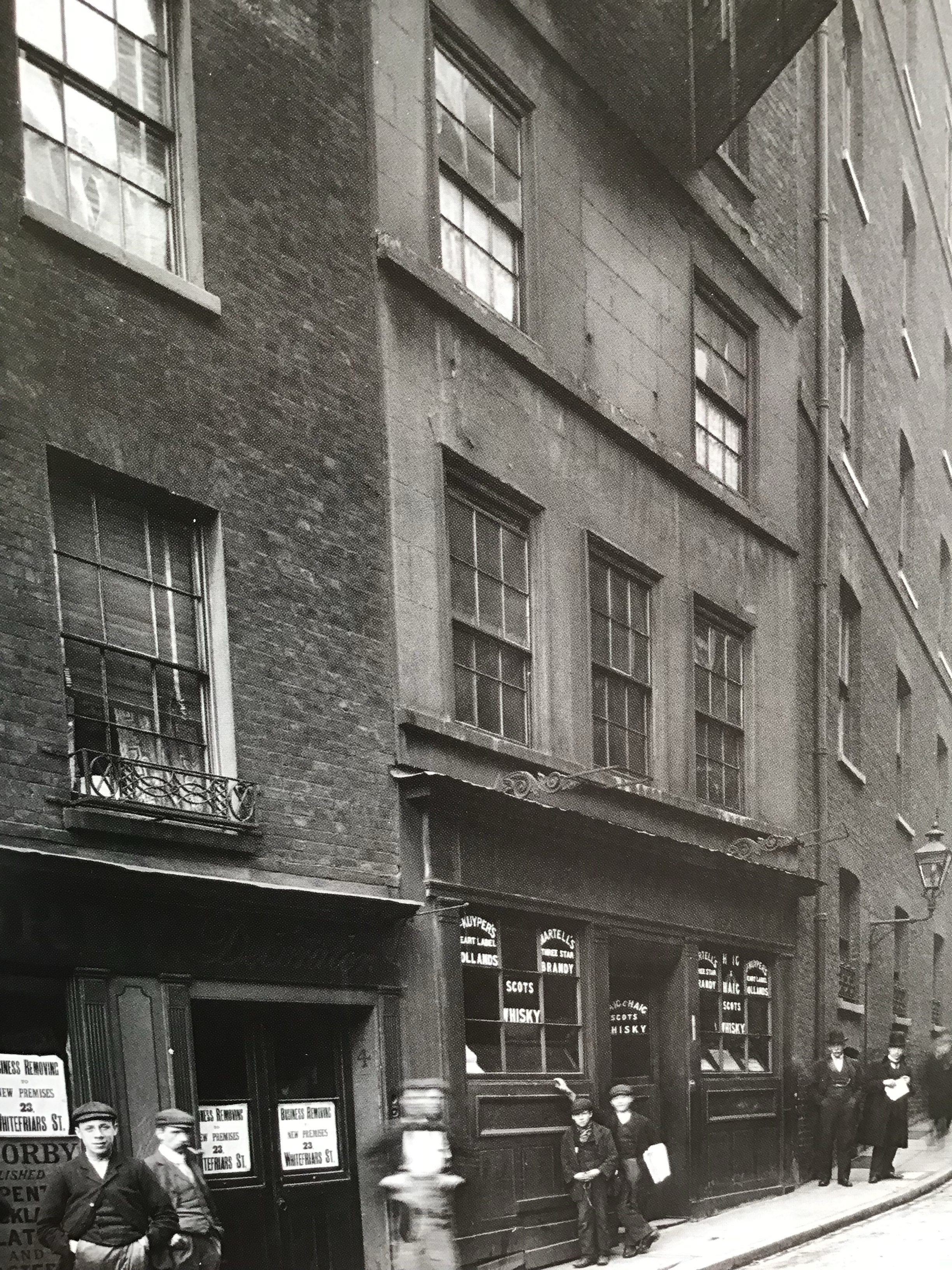

12, Millers Court was literally just a few steps away from 13, Millers Court where ‘Jack the Ripper’ murdered his last victim, Mary Jane Kelly, on 9 November 1888. The murder took place at Mary Jane Kelly’s lodgings, which were situated at No.13, Miller’s Court. The lodgings, if you can describe it like that, consisted of a single room just 10ft x 12ft, which was a partitioned section of the ground floor of the main house. This was in reality the back end of number 26 Dorset Street. Millers Court was accessed via a narrow alley which led into a courtyard at the back. The only door was just inside the arched entry to the court, which was entered from a passageway between 26 and 27, Dorset Street. The area of Spitalfields was well known for its common lodging houses. These were squalid and nasty places to bunk down, but people had to, there was no other choice. They were places for the poor and rooms would be let on a nightly basis. Many would hope to raise enough money in the day so they could have a bed for the night. At the time Mary Kelly was murdered Dorset Street was full of common lodging houses which could sleep vast numbers of people a night. They were often extremely overcrowded and unhygienic.

You will have no doubt noted that the second address given on Adelaide’s school admission records was 26, Dorset Street. Which was in effect part of Millers Court. It’s impossible to say whether Adelaide’s parents were living in Millers Court at the time of Mary Kelly’s murder, but it’s extremely likely they were within a stone’s throw of the murder scene at the time. Poor Adelaide herself was born just 5 years after the murder of Mary Jane Kelly. A Canadian Newspaper Reporter named Kit Watkins later reported visiting the room that Mary Jane Kelly was murdered in, five years after the murder had taken place, to find bloodstains on the walls and floor which the Landlord hadn’t even bothered cleaning off before letting the room to the next tenants. We can never prove or disprove that story, but it’s certainly a very sobering thought.

(13, Millers Court – Where Mary Kelly was Killed. The alley on the right leads to Dorset Street. The photograph was taken just after the murder.)

The entrance to Millers Court from Dorset Street is shown in the picture above which was taken by Leonard Matters in 1928. The entrance to Millers Court can be seen by the alleyway next to the picture in the chair.

(Layout of Miller’s Court)

There were at least two more murders that I was able to discover that were directly associated with both 12 and 13 Millers Court. On 26 November 1898, Elizabeth Roberts was murdered in the room above 13 Millers Court, where Mary Jane Kelly was murdered ten years before. Then in the early hours of 2 July 1909, Katherine Roman, known as Kitty Roman, was also found murdered in her room at 12 Millers Court.

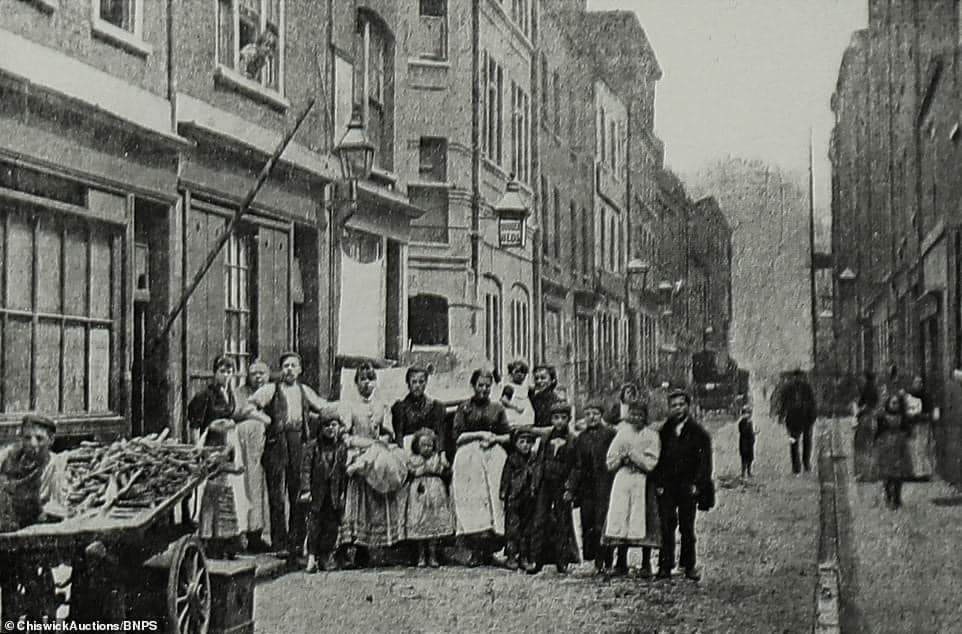

The word ‘Poverty’ does not begin to describe the deprivation and despair that hung in the air around the streets of Spitalfields at the time. What struck me the most, above all else, was the lack of ‘hope’, there was absolutely no hope of escaping their current situation and no hope of any kind of future. Once you remove a person’s hope they have nothing to live for.

Dorset Street was once described in a book by Fiona Rule as ‘The Worst Street in London’ and this was without any exaggeration. It was the haunt of thieves, murderers and prostitutes and the sanctuary of persecuted people. It was absolutely the last resort for those who couldn’t afford anything else. So notorious was this street in the 1890s that policemen would avoid the area and only patrol the streets in pairs. Behind every grimy window lay iniquity, vice and violence, with the labyrinth of streets, courts and alleys boasting on average, a murder every month. Fear lurked like a dark shadow around every corner and Dorset Street’s reputation was confirmed in the Charles Booth London Poverty Survey of 1898. The maps presented the social conditions of the people of London according to seven classes. Booth, an industrialist and social philanthropist, had set out to conduct a study into the economic and industrial situation across London, on a street-by-street basis. As part of Charles Booth’s research for his poverty map, he sent inspectors to accompany police officers on their beats, walking around the streets of London and making notes on their observations. On 17 March 1898 George Duckworth walked with Sergeant French around Dorset Street and reported in his notes that Dorset Street was;

“The worst street in London” describing it as “the worst street I have seen so far, full of thieves, prostitutes, bullies, all in common lodging houses”.

Unsurprisingly Charles Booth colour-coded the Street with the bottom rating, shading it black, which was described as ‘vicious and semi-criminal’. It was nicknamed by the locals as ‘Do As You Please Street’ and the Street’s reputation was so bad that it was eventually renamed Duval Street in 1904.

(Booth’s Poverty Map of Spitalfields)

(Dorset Street)

(Dorset Street)

So how did a Street like Dorset Street come to exist?

With London’s population growing exponentially, there was increasing pressure on the City to provide cheap affordable housing, especially for the growing and expanding London Docks. For as long as it has existed, the East End of London has been regarded as the ‘tough’ end of London, a place of extreme overcrowding and poverty, where only the strongest survived. Over the course of just one hundred years, the term ‘the East End’ became synonymous with poverty, overcrowding, disease and crime, with row upon row of houses crammed into such small areas, each street immediately backing onto the next one. For the respectable, there was a poor home, the less fortunate rented a room, those at the lower end could afford a common lodging house and for those that remained the choice was the streets or the workhouse.

Living conditions were cramped, squalid and pretty miserable. In response to demand, common lodging houses, like those in Dorset Street, sprung up to cater for those needing a place to live. These lodging houses offered rooms on a nightly basis and were frequented by those on the fringes of society, including common criminals and prostitutes, as well as those too sick or too old to work. Soon the housing in the courts and alleys became infested with people and crime. Disease and illness spread like wildfire in the suffocating atmosphere. Dorset Street was a Street that lived in perpetual shadow, the air and atmosphere tainted by centuries of poverty, crime and sorrow. A Street that was full of darkness where such little value was placed on a persons life.

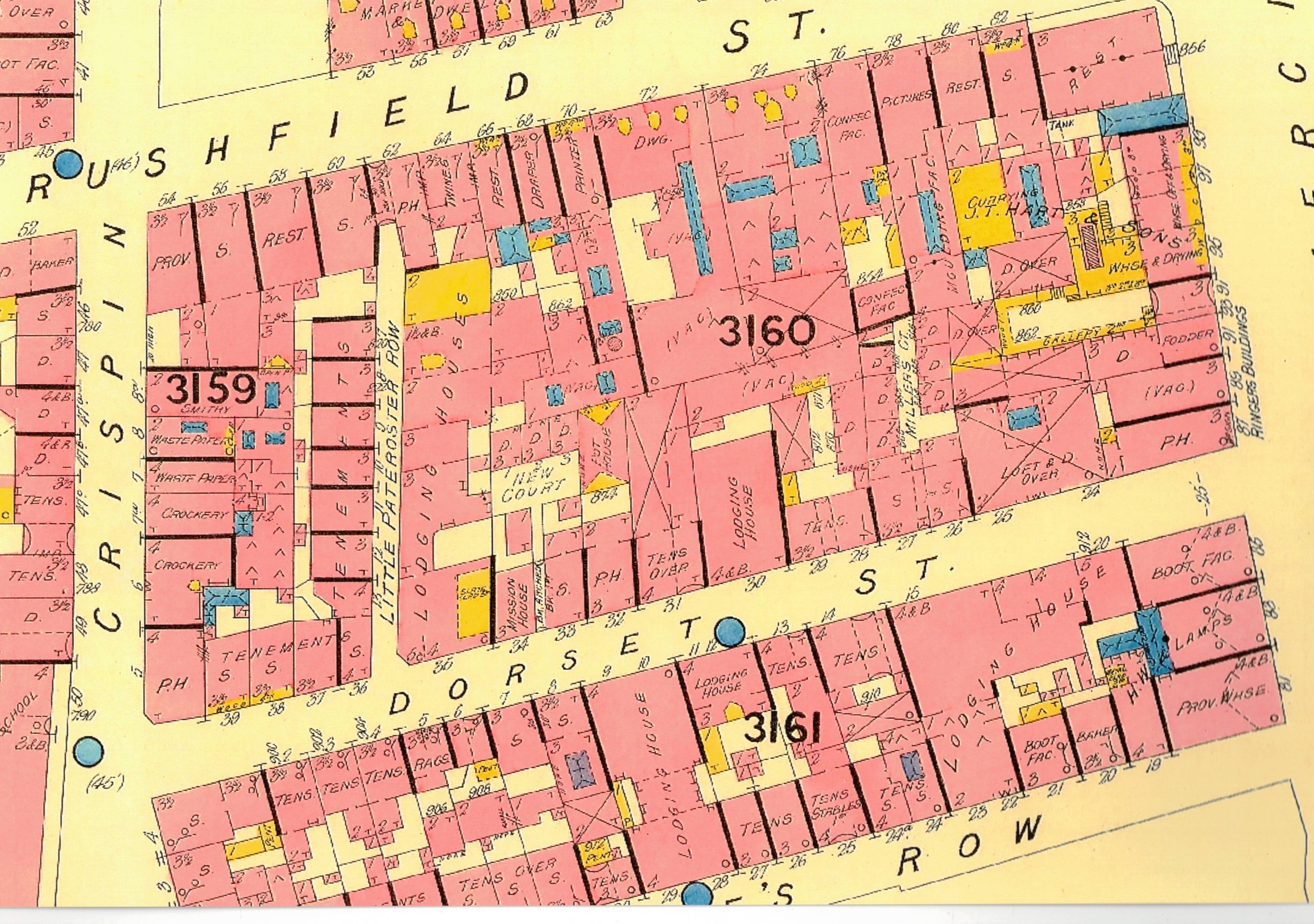

(The Goad Fire Insurance Plan of London showing Dorset Street and Millers Court)

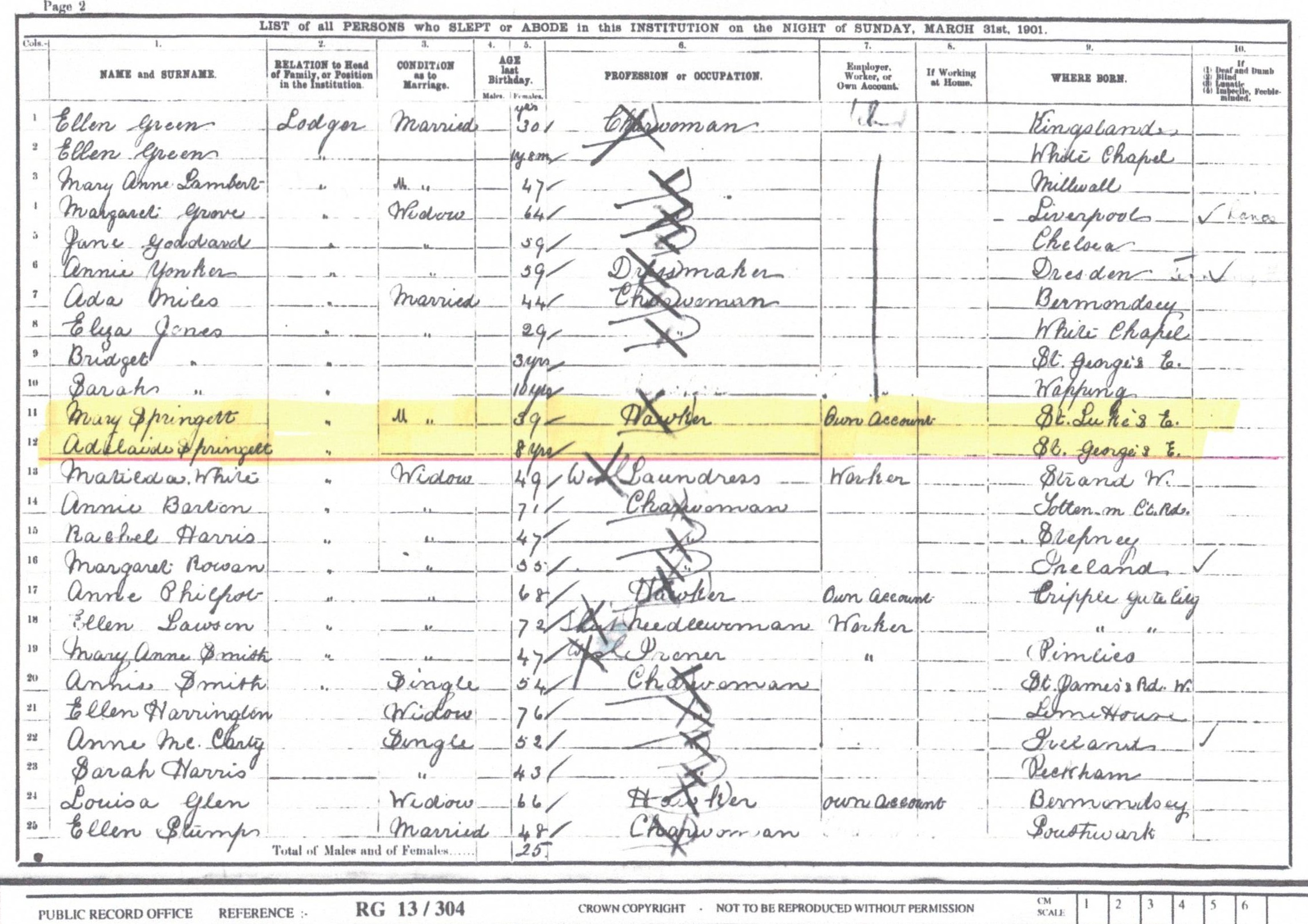

We have to remember that in among the squalor, poverty and crime were children like Adelaide. Living from hand-to-mouth with the only goal being survival for another day. Generation after generation born into abject poverty with no chance of ever breaking the cycle. The poor children like Adelaide knew only of this life. They played happily in the streets oblivious to their surroundings, but only the strongest would survive these harsh conditions, but survive young Adelaide did. We next find Adelaide in the 1901 census lodging with her mother in the Salvation Army Shelter in Hanbury Street. Adelaide’s mother, Mary Springett is recorded as a hawker working on her ‘own account’. Adelaide’s only surviving sibling, William John Springett can be found on the 1901 census at the Catholic Boy’s home in St. George The Martyr in Southwark. There is no trace of Adelaide’s father and my suspicion is that he was either in Prison or the Workhouse.

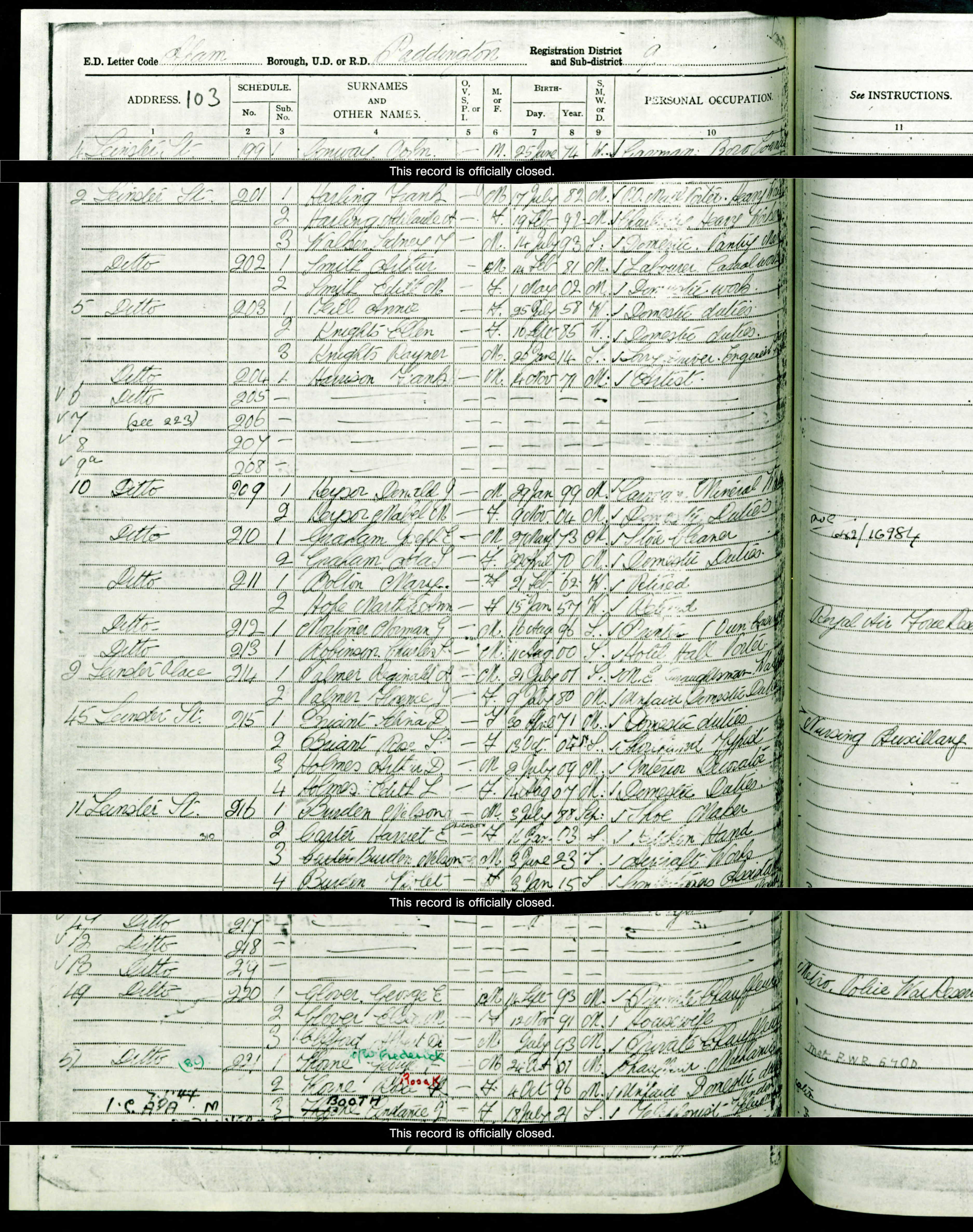

(1901 Census for Adelaide Springett and Margaret Springett – Class: RG13; Piece: 304; Folio: 79; Page: 2)

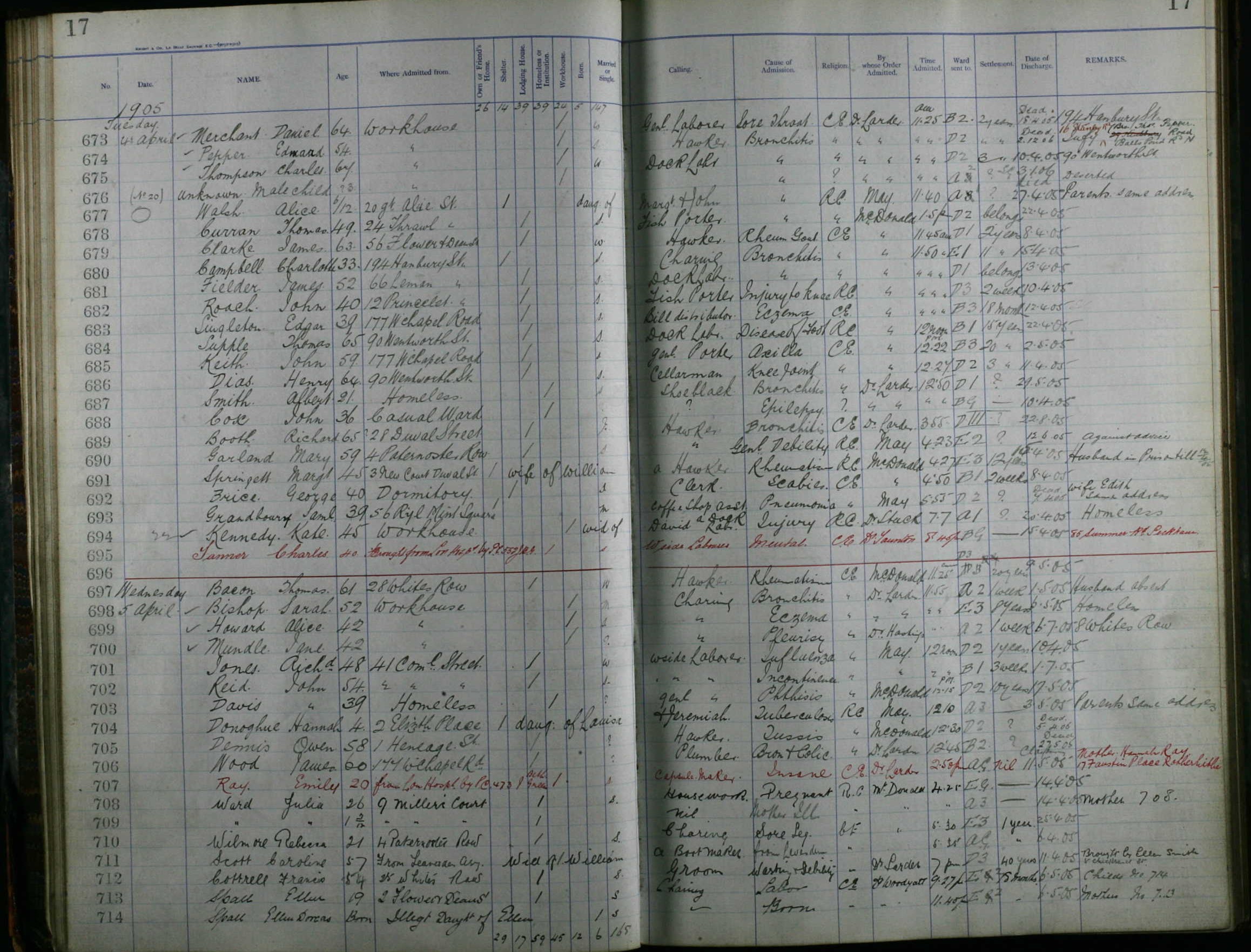

If we thought that life was already tough for poor Adelaide, then things were to turn a lot worse just a few years after the 1901 census was taken. On 4 March 1905, Adelaide’s mother, Margaret Springett is back in the Whitechapel Infirmary and her father appears to be in prison according to Margaret’s admission record. Her release date from the Infirmary (14 Apr 1905) appears to have been changed to coincide with her husband’s release date from prison, according to the records. We have to wonder where poor Adelaide was living during this period, was she in service, or maybe the workhouse at the time? A later newspaper article, shown below does give some insight into where Adelaide was residing at the time.

(Margaret Springett Workhouse Record – London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: STBG/WH/123/040)

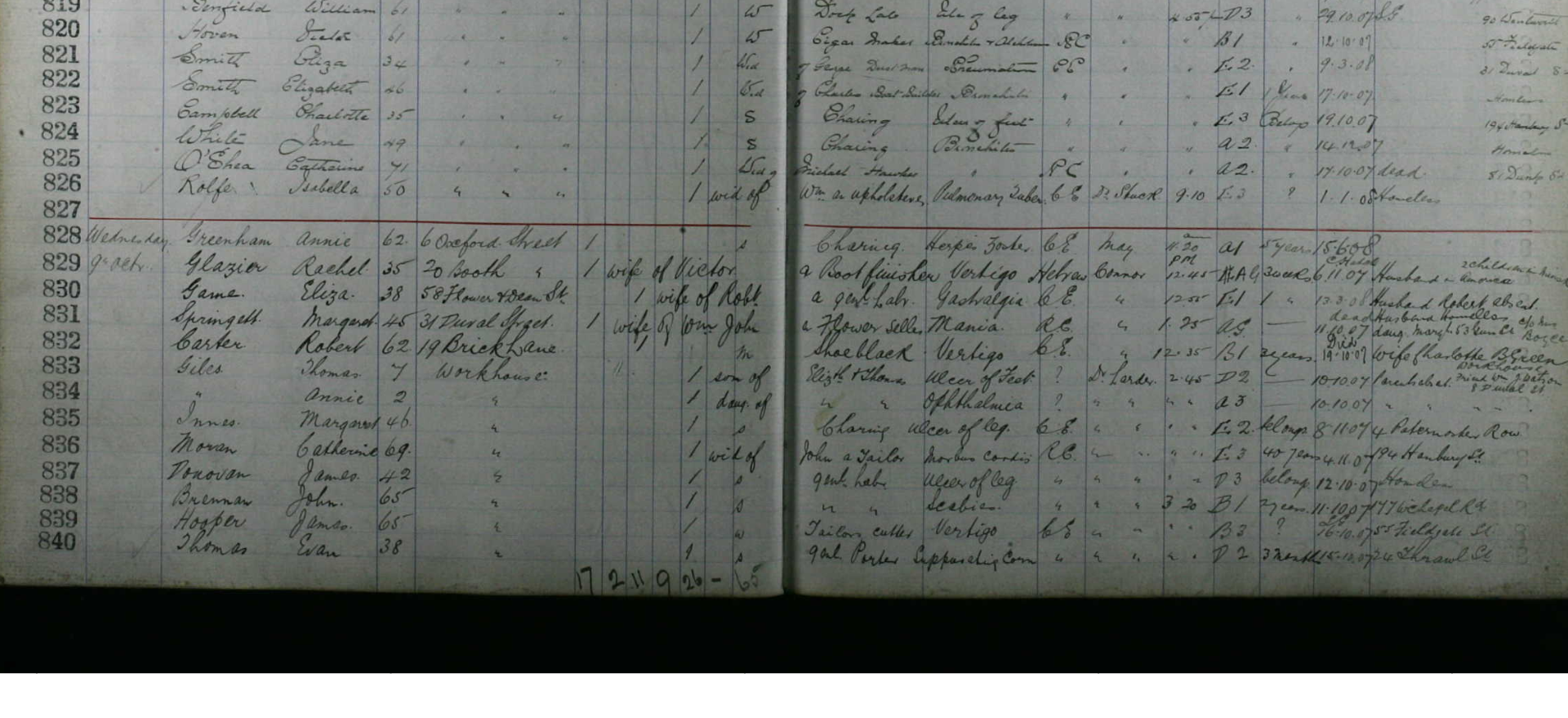

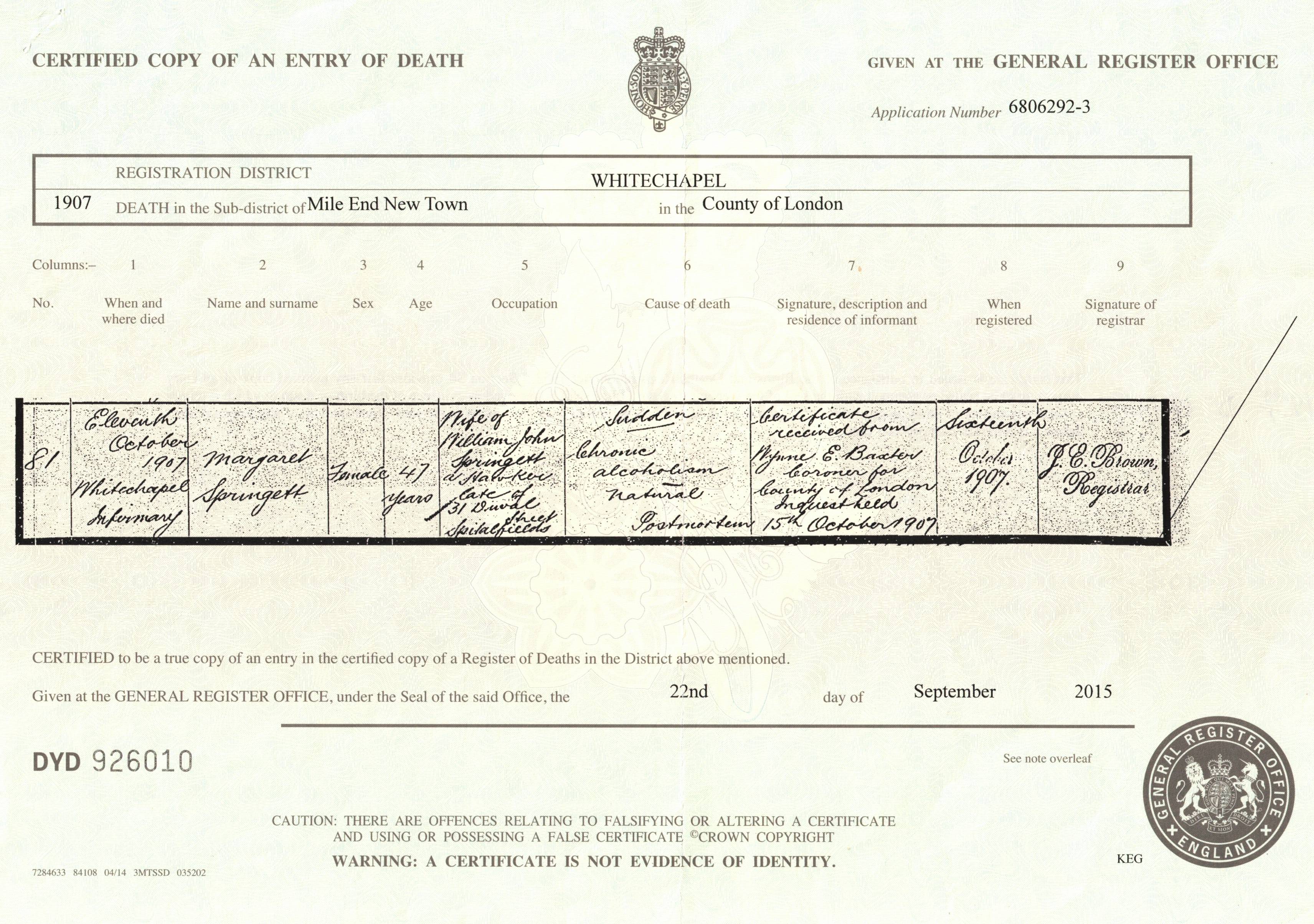

Sadly Margaret Springett’s next visit to the Infirmary would be her last. At 1:25 on Wednesday 9th Oct 1907, Margaret Springett, flower seller, aged 45 was admitted once again to the Workhouse Infirmary, this time suffering from Mania. Just two days later, on the 11th Oct 1907 tragically she died. The address on her admission and on her death certificate is recorded as 31, Duval Street, which we already know was the notorious Dorset Street, dubbed “The worst street in London” after the Street had been renamed. Her cause of death was recorded as Sudden – Chronic Alcoholism which was described as ‘natural’. We can only speculate as to the decline in Margaret’s condition, but what we do know from the records is that she lost three young children within four weeks of each other and her living conditions would have been extremely difficult and almost unbearable, maybe turning to drink was her only way of escaping the hell that she might have felt that she was in at the time. There was a pub on almost every corner and this might have provided the only solace given her desperate circumstances. Dorset Street itself had three pubs, The Horn of Plenty at one end, The Britannia at the other end and The Blue Coat Boy in the middle. Within walking distance just around the corner was the Ten Bells which was the regular haunt of two of Jack The Ripper’s victims.

(Margaret Springett’s Workhouse Entry – London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: STBG/WH/123/043)

(Death Certificate for Margaret Springett)

As this tragic story unfolds, each layer reveals its own depressing tale of sorrow, loss and poverty. As we peel back the layers and turn each chapter, it’s almost incomprehensible to imagine that Adelaide was just a child, she was still only 14 when her mother died and had already suffered enough loss to last a lifetime and yet more suffering was still to come.

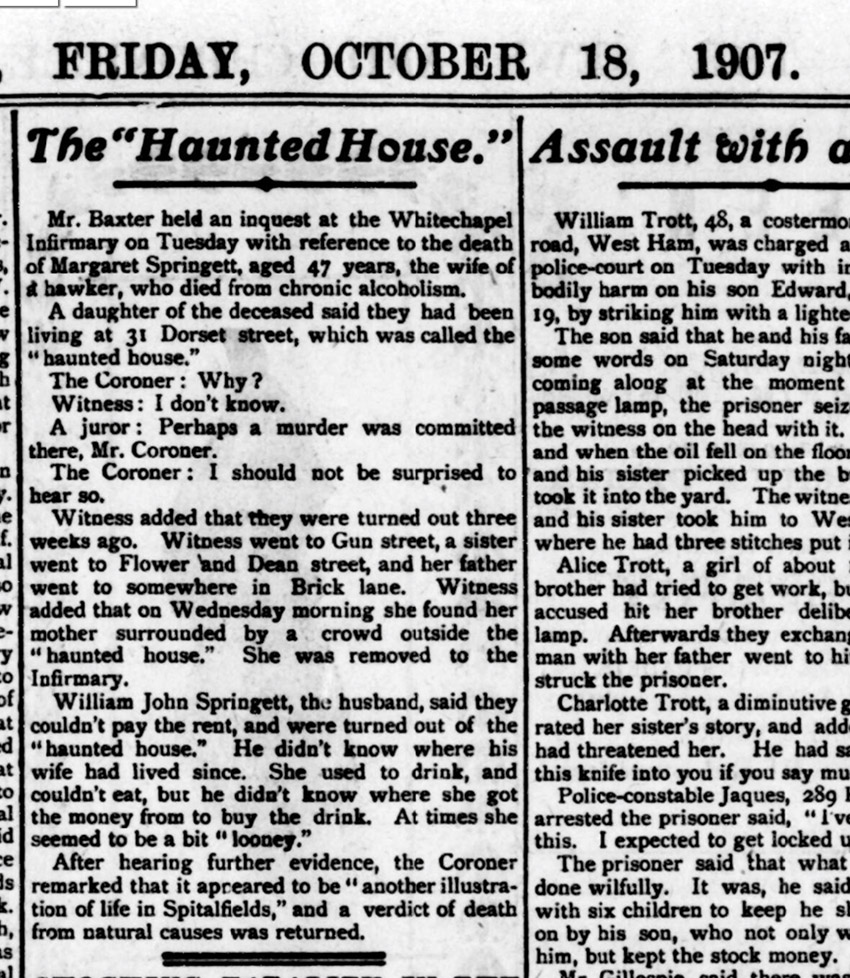

A newspaper report into the inquest into her poor mother’s death revealed even more heartbreak and sorrow as we learn that at the tender age of 14, young Adelaide was to actually witness the tragic circumstances leading up to her mother’s demise. Adelaide’s poor mother was found collapsed on the pavement outside her lodging house by a crowd, which included young Adelaide herself. The lodging house was described as The “Haunted House” in the newspaper article, clearly a reference to the earlier Murder of Mary Jane Kelly.

The newspaper report does make an awfully tragic, but all too familiar tale for the area at the time.

On 18 October 1907, The East End News and London Shipping Chronicle reported the following on Margaret Sporingett’s death:

“Mr Baxter held an inquest at the Whitechapel Infirmary on Tuesday with reference to the death of Margaret Springett, aged 47 years, the wife of a hawker, who died from chronic alcoholism. A daughter of the deceased said they had been living at 31 Dorset Street, which was called the “haunted house.” The Coroner: Why? Witness: I don’t know A juror: Perhaps a murder was committed there, Mr. Coroner. The Coroner: I should not be surprised to hear so. Witness added that they were turned out three weeks ago. Witness went to Gun Street, a sister went to Flower and Dean Street, and her father went to somewhere in Brick Lane. Witness ‘ added that on Wednesday morning she found her mother surrounded by a crowd outside the “haunted house”. – She was removed to the Infirmary. William John Springett, the: husband, said they couldn’t pay the rent, and were turned out of the “haunted house.” He didn’t know where his wife had lived since. She used to drink, and couldn’t eat, but he didn’t know where she got the money from to buy the drink. At times she seemed to be a bit “looney.” After hearing further evidence, the Coroner remarked that it appeared to be ” another illustration of life in Spitalfields,” and a verdict of death from natural causes was returned.

(Dorset Street at the intersection with Crispin Street 1904)

To be factually correct in the newspaper article, it was her 21 year-old brother William John Springett and not a sister as the article states, who went to Flower and Dean St. What this newspaper report does give us, is a clue as to the whereabouts of Adelaide at the time, we now know that she was living at Gun Street, in Spitalfields. The later Hospital record shows that she was living and working for Mrs Boyes at 53, Gun Street. We also know from this newspaper article that Adelaide’s only surviving sibling, William John Springett was also still alive, he is noted as living at nearby Flower and Dean St. From his military attestation papers we can see that William John Springett joined the 6th Militia Battalion on 30 January 1907, aged 20 and he gives his address as 8, Whites Row in Spitalfields. The Militia were the forerunners of what we know today as The Territorial Army. He lists his parents, William and Margaret Springett as his next of kin, also residing at 8 Whites Row, Spitalfields. Whites Row, like many of the addresses in the area at the time was described as a large well established “doss house”.

The map above shows the close proximity of Dorset Street and White’s Row and is another indication that the family were moving from lodging house to lodging house, all within the same few streets.

The Whitechapel Infirmary was an institution that played a large part in Adelaide’s family’s life and she was admitted there herself on Tuesday 8 Jun 1915, aged 22. She stayed until 19 Jun 1915, being treated for Erysipelas, which is an unpleasant skin condition, usually caused by a scratch becoming infected, sadly no antibiotics back in those days. Her occupation is recorded as ‘servant’ and her address was given as Gun Street, Spitalfields. This record confirms the newspaper report on her mother’s death where we know that she gave her address as Gun Street. The Hospital record confirms that she was there ‘in service’.

(London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: STBG/WH/123/050)

Sadly I have been unable to find a record for Adelaide in the 1921 census, chances are she was still in service somewhere or even possibly in the workhouse.

Like many of the family history stories that we discover, this story is built upon multiple layers. As each layer unravels it reveals less hope and more despair for poor Adelaide. I must admit that at this point in her life, I was hopeful that there might have been a glimmer of light for young Adelaide and that she had found some comfort and happiness in her life. However, just when you think that this story cannot possibly get any darker, once more, things take a turn for the worse and send poor Adelaide spiralling into yet another dark chapter of her life.

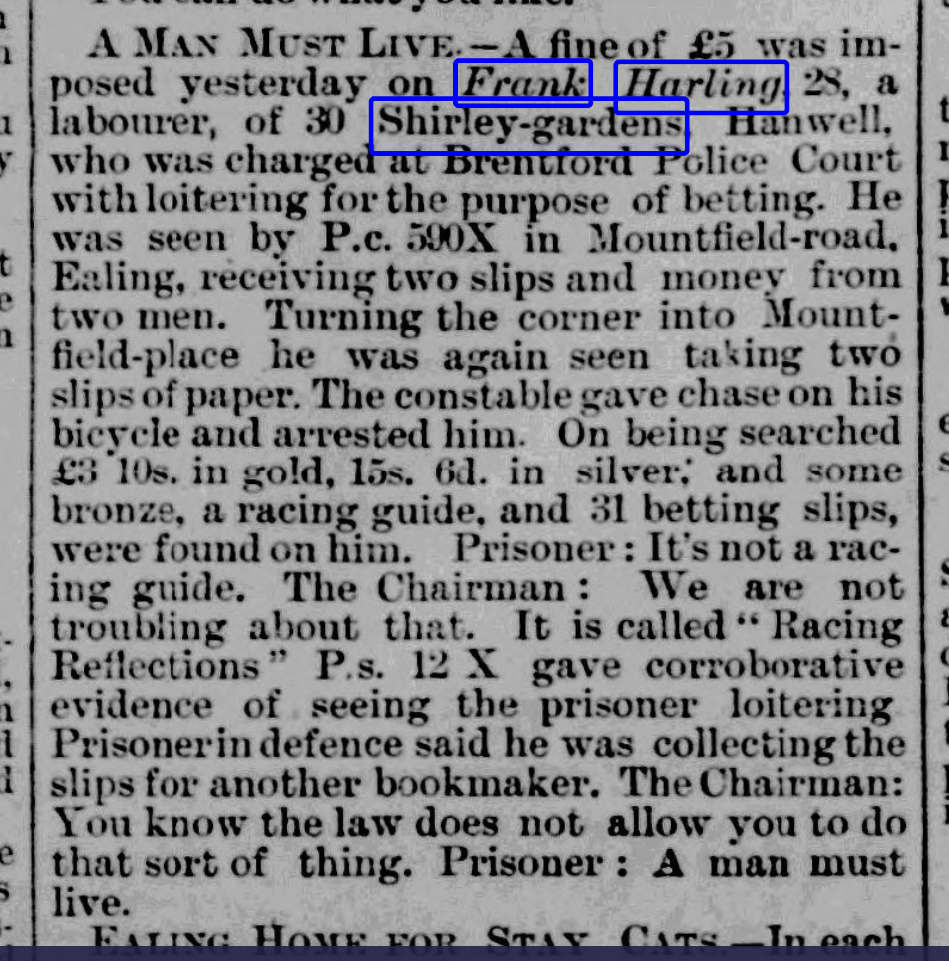

Working from the records that I have found and going backwards in time from her later death to this point, I now know that at some point in the 1930’s she met a man named Frank Harling and although no record exists of a marriage between the couple, I know that they co-habited together as husband and wife, with Adelaide even using the name ‘Adelaide Harling’. One would think that this was maybe a turning point in her life, but sadly once more she was cast into the abyss.

(The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1939 Register; Reference: Rg 101/412e)

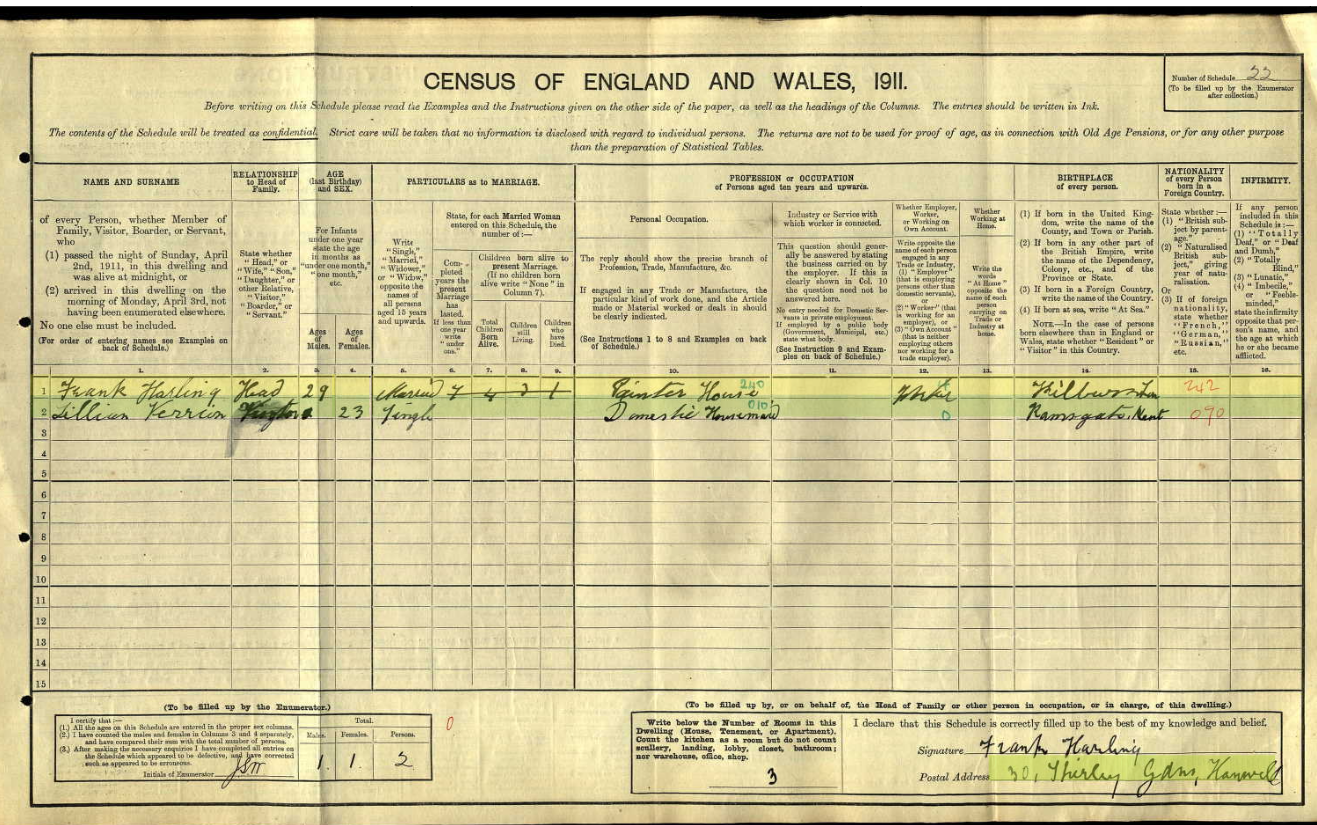

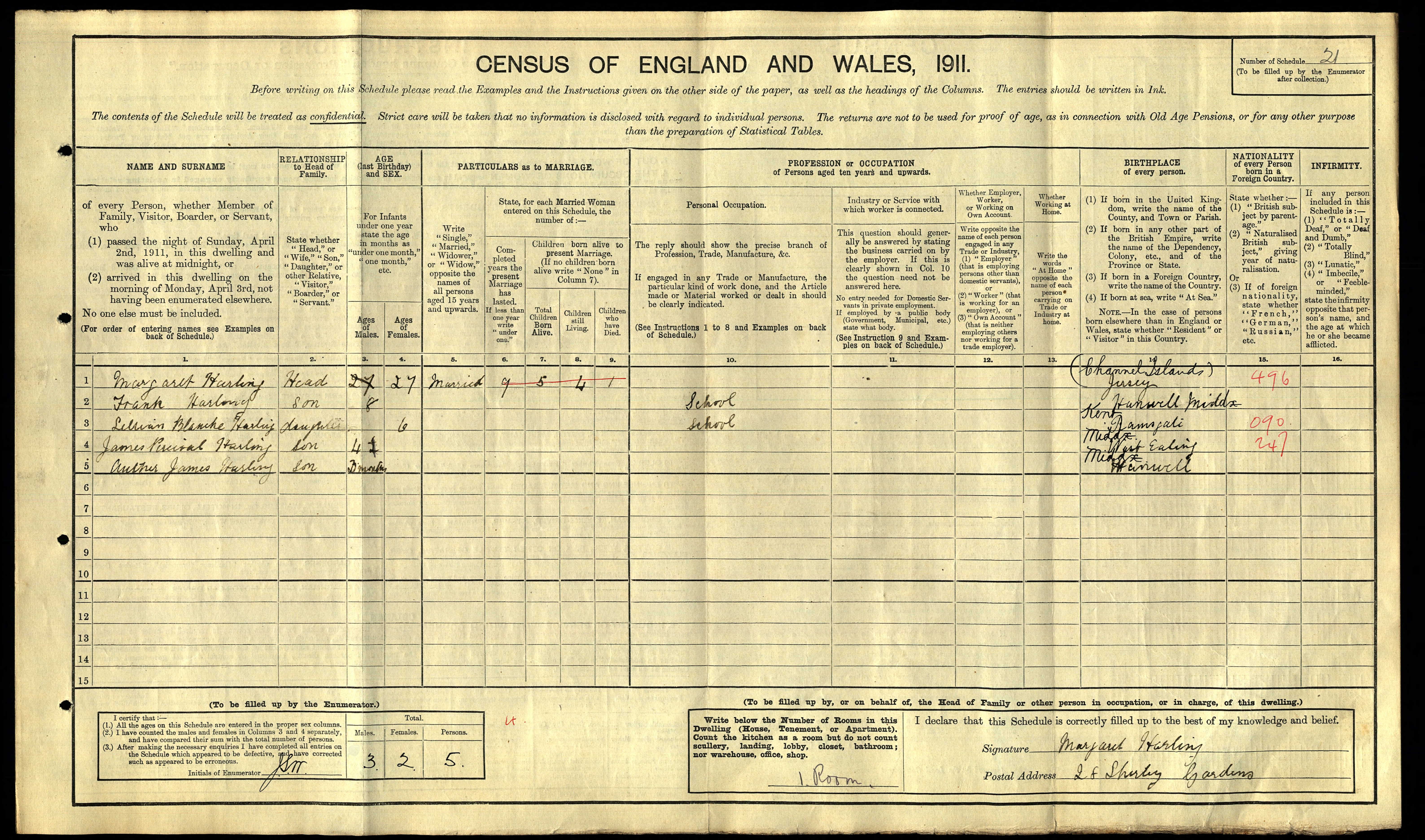

The 1939 Register records Frank Harling and Adelaide A Harling living at 2, Leinster Street in Paddington. The image is rather difficult to read, but it looks like Adelaide is recorded as a Char, one assumes Char Lady ‘Heavy Works and Frank is recorded as a P.O. Mail Porter. It was when I started researching Frank’s story that an extremely darker side emerged, but if we are to be truthful to her story and the facts, we cannot airbrush the awful story that these documents reveal. In 1911 we find Frank living at 30, Shirley Gardens, here he is recorded as a House Painter born in Kilburn in London, aged 29 and he is recorded as being married. Living at the same address was a single lady named Lillian Verrion aged 23 who was a domestic servant. Nothing leaping off the page so far. However, there’s always a however! Living next door at number 28 are Frank’s wife Margaret Harling and his 4 children. It’s almost impossible to view a set of documents without forming an opinion, but here all I will say is that seven years before the census, Frank Harling had married Margaret Verrion and YES he was living next door with her younger sister Lillian Verrion at the time the 1911 census was taken. A later newspaper report leaves little to the imagination about what went happened here and can be found below.

(1911 Census for Frank Harling – The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911)

(1911 Census for Margaret Harling – The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911)

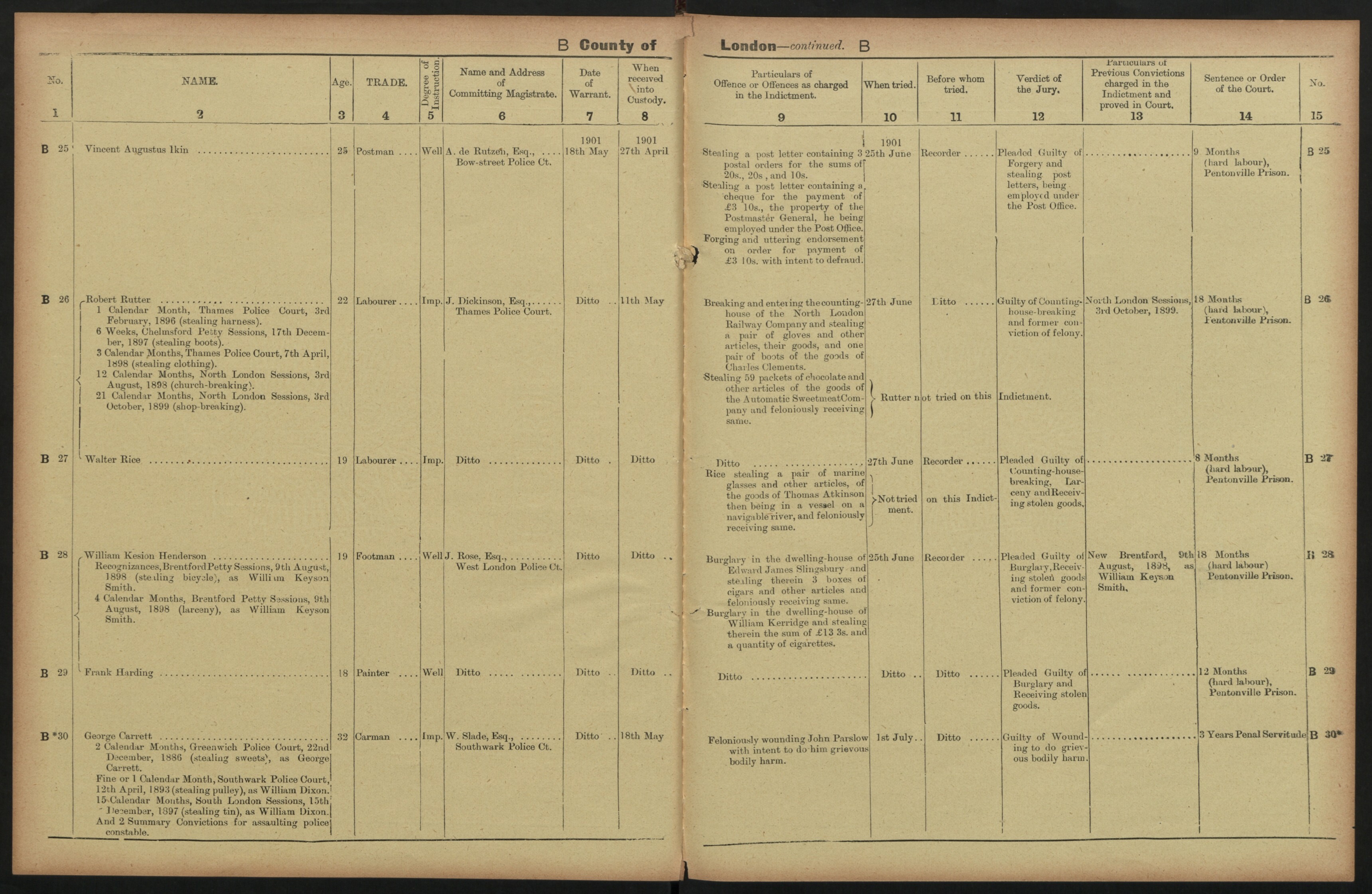

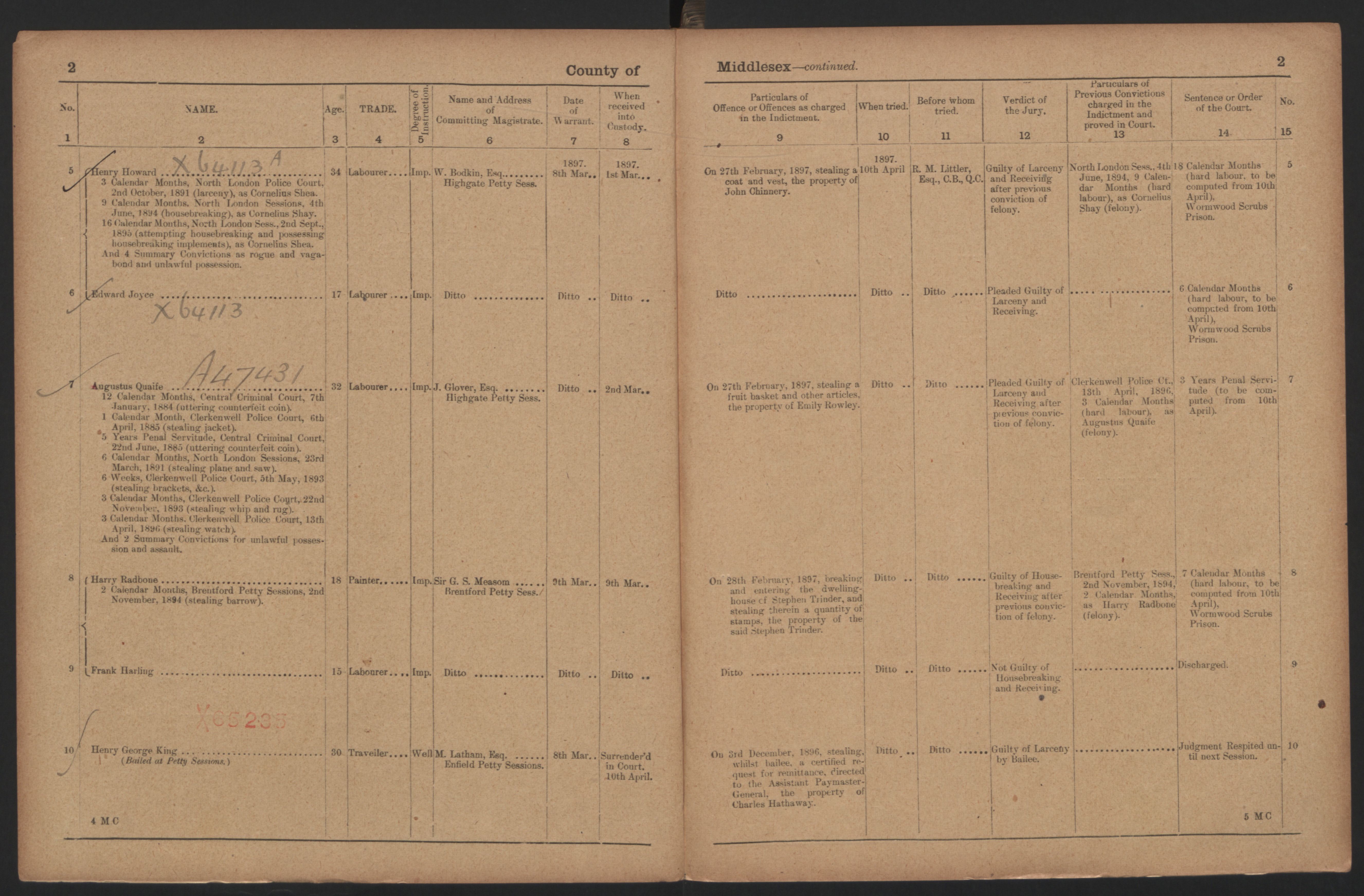

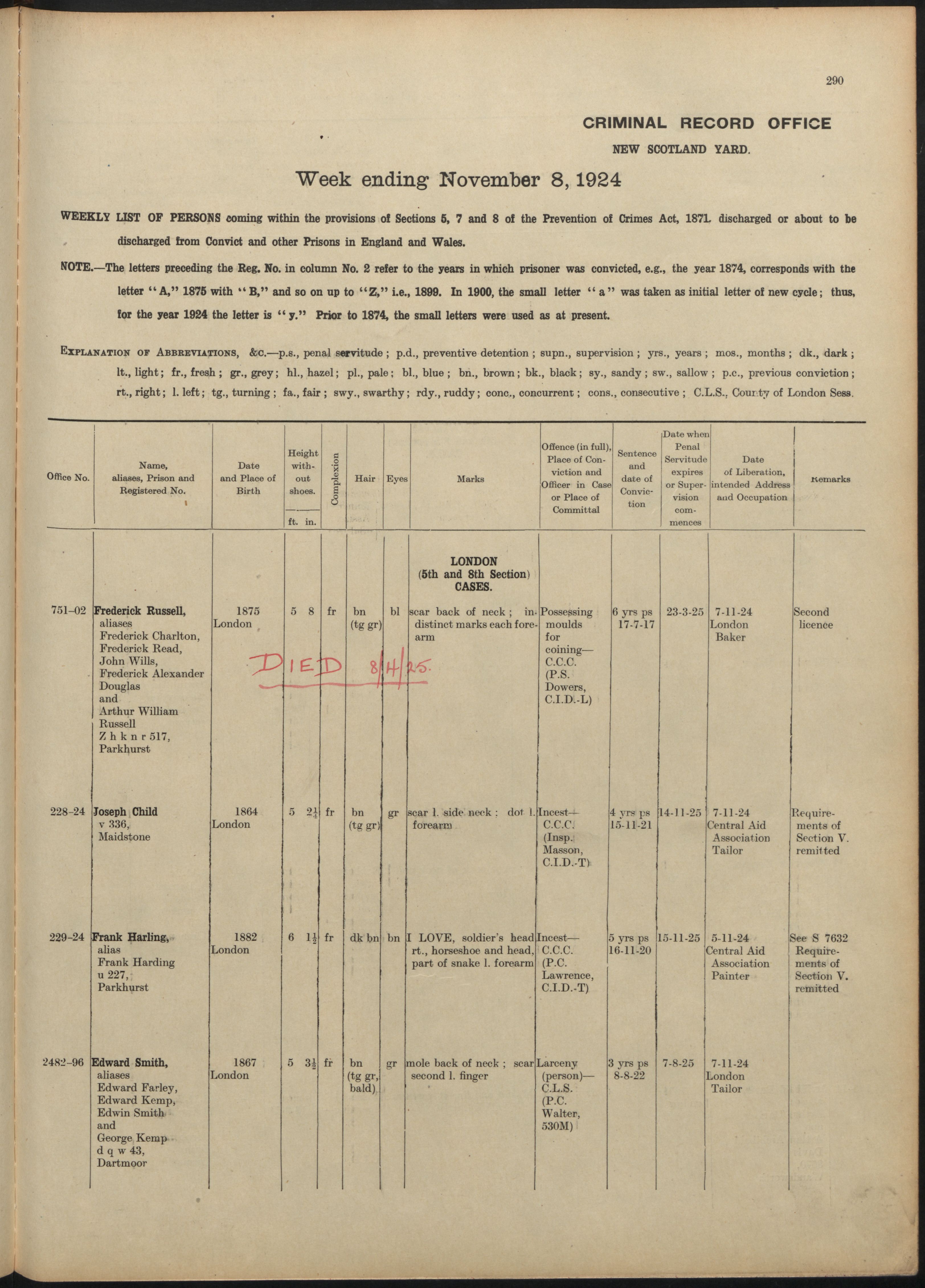

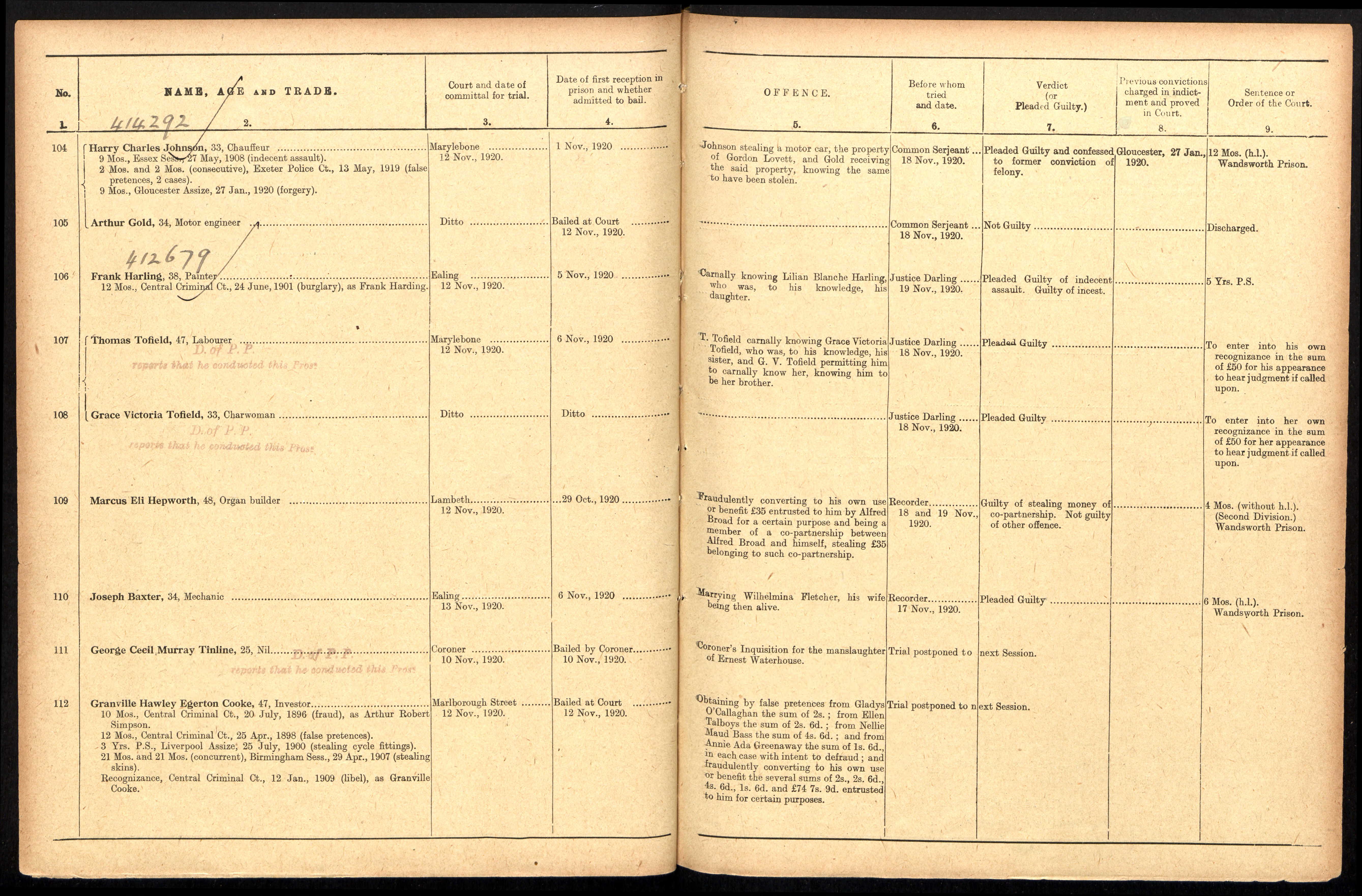

Once more as I turn the pages of the record books the story gets even darker. I would say, without a doubt, that this is one of the darkest passages that I have ever written. These documents and records speak for themselves and leave little room for imagination or even forgiveness. Frank Harling appears in several police and prison records, covering a period from 1897 to 1920, Included among these records is a record for ‘Habitual Criminals’. The first record shows that Frank, who was using the name Frank Harding at the time, was sentenced to 12 months hard labour by the Central Criminal Court on 24 June 1901 for the Burglary of the property of William Kerridge, plus also the Burglary of a property owned by an Edward James Shipley. This was to be the start of many years of criminal activity. But it is the fourth record that is the most difficult record to read. Frank Harling pleads GUILTY to ‘carnally knowing Lilian Blanche Harling who was, to his knowledge his daughter’. I will let that record speak for itself………He was sentenced to 5 years imprisonment for his crime, at HMP Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight.

(The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 140 Home Office: Calendar of Prisoners; Reference: HO 140/178)

(The National Archives; Kew, London, England; MEPO 6: Metropolitan Police: Criminal Record Office: Habitual Criminals Registers and Miscellaneous Papers; Reference: MEPO 6/36)

(The National Archives; Kew, Surrey, England; CRIM 9: Central Criminal Court: After Trial Calendars of Prisoners; Reference: 66)

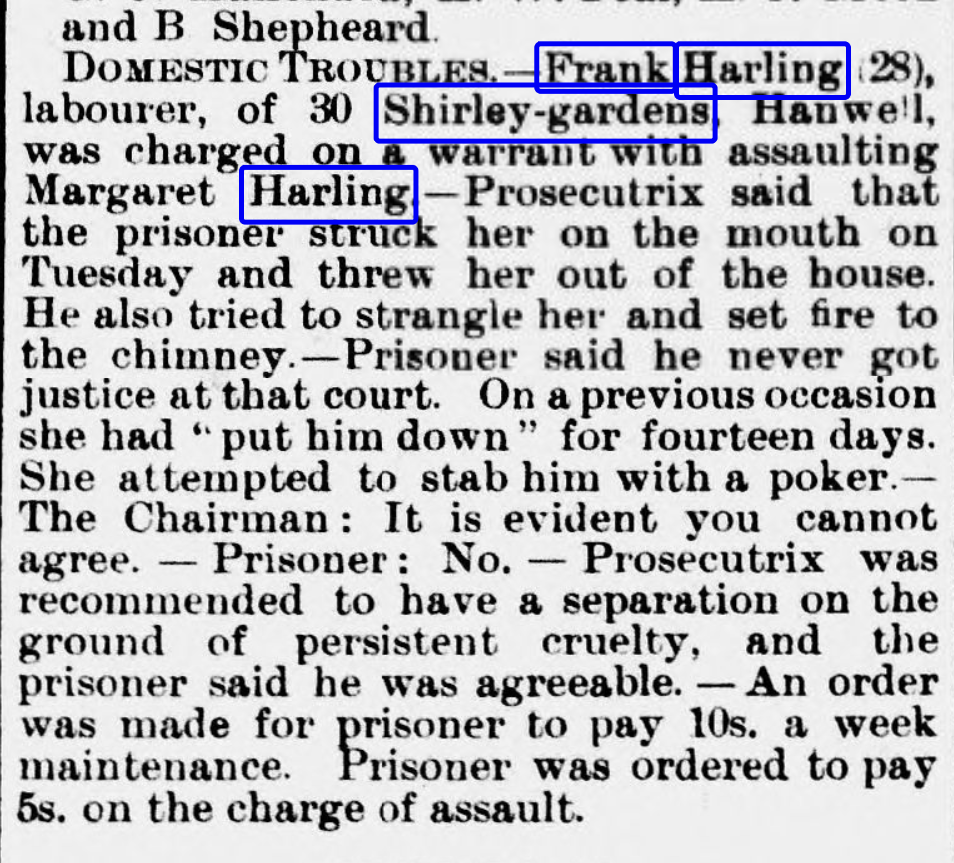

I was unable to find any further records for Frank Harling in the criminal records that are available online. Now whether there are more records to be found, or he just got better at covering his tracks, we will never know. The positivity in me would hope that after meeting Adelaide he turned the corner, but that is one of those questions that we cannot answer with any certainty, only time will tell if more records are to be found at a later date. Did Adelaide know of his womanising and dark past, again a question that will forever remain unanswered. Further newspaper reports leave little doubt as to the character of the man and give a possible explanation for the earlier 1911 Census. Literally just a couple of weeks before the 1911 census was taken, the Hanwell and Brentford Observer reported on 18 March 1911;

Domestic Troubles – Frank Harling, 28, labourer, of 30 Shirley Gardens, Hanwell was charged on a warrant with assaulting Margaret Harling – Prosecutrix said that prisoner struck her on the mouth on Tuesday and threw her out of the house. He also tried to strangle her and set fire to the chimney. – Prisoner said he never got justice at that court. On a previous occasion, she had “put him down” for fourteen days. She attempted to stab him with a poker. – The Chairman: It is evident you cannot agree. – Prisoner: No. – Prosecutrix was recommended to have a separation on the grounds of persistent cruelty, and the prisoner said he was agreeable. – An order was made for Prisoner to pay 10s. a week maintenance. Prisoner was ordered to pay 5s. on the charge of assault.

It’s impossible at this point not to make any judgments, but all I would say is that he sounds like an extremely unsavoury character in every respect, this adds further support to the 1911 census and also gives us a glimpse into the real side of the man that was Frank Harling.

(From The Hanwell Gazette and Brentford Observer)

A later newspaper report dated 20 August 1910, finds Frank Harling charged with loitering for the purposes of betting and fined £5. What immediately struck me was the fact that he was only ordered to pay 5s for the assault, yet was fined £5 just for loitering with the intention of betting.

(From The Hanwell Gazette and Brentford Observer)

I have to believe in my own mind that Adelaide had no idea of his criminal past, but a man of this character, could he change? Could he hide his cruel and vile nature? I have my doubts somehow. What brought the two of them together we will never know, but if she knew of his past was she hoping he had changed or hoping that she could change him herself? So many questions that we don’t have the answers to. I wan’t to believe that Frank had left his criminal past behind him and that at last Adelaide was to find some comfort in her life. The pendulum of life surely has to swing in favour of Adelaide at some point.

Just pausing Adelaide’s story for a second and taking a breath, we have to remember that Adelaide did have one surviving sibling, namely her older brother William John Springett. We know from his military records that he joined the Middlesex Militia and later served with ‘B’ Company in the Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge’s Own), 3rd Battalion in Loos and Salonika during The Great War. I would love to know if Adelaide and her older brother were still in contact at this point. The romanticist and optimist in me would hope that Adelaide and her brother maybe even exchanged letters during the War. I want to believe that Adelaide sat waiting for the arrival of his every letter, sent from the front line. I can picture her now, working in service, praying and hoping that she would see him once again. Looking out of the window of her bedroom, clutching his letters to her chest, praying for the best, but preparing herself for the worst. There has to be some light in amongst all the darkness.

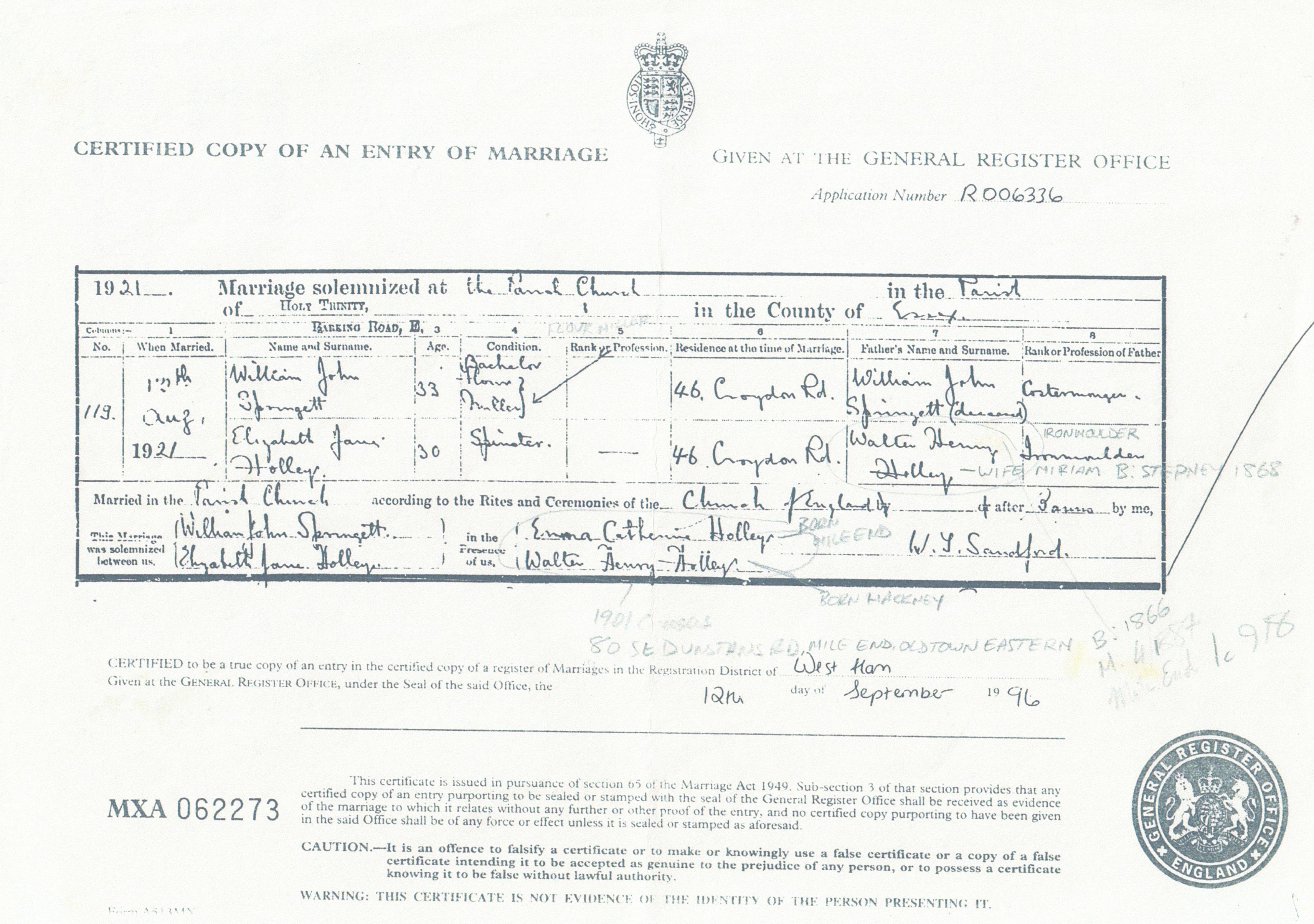

William was to survive the war and he married Elizabeth Jane Holley on the 13 Aug 1921. The two witnesses to the wedding were from Elizabeth’s side of the family which makes me wonder if indeed William and Adelaide remained in contact.

(Marriage Certificate for William John Springett and Elizabeth Jane Holley)

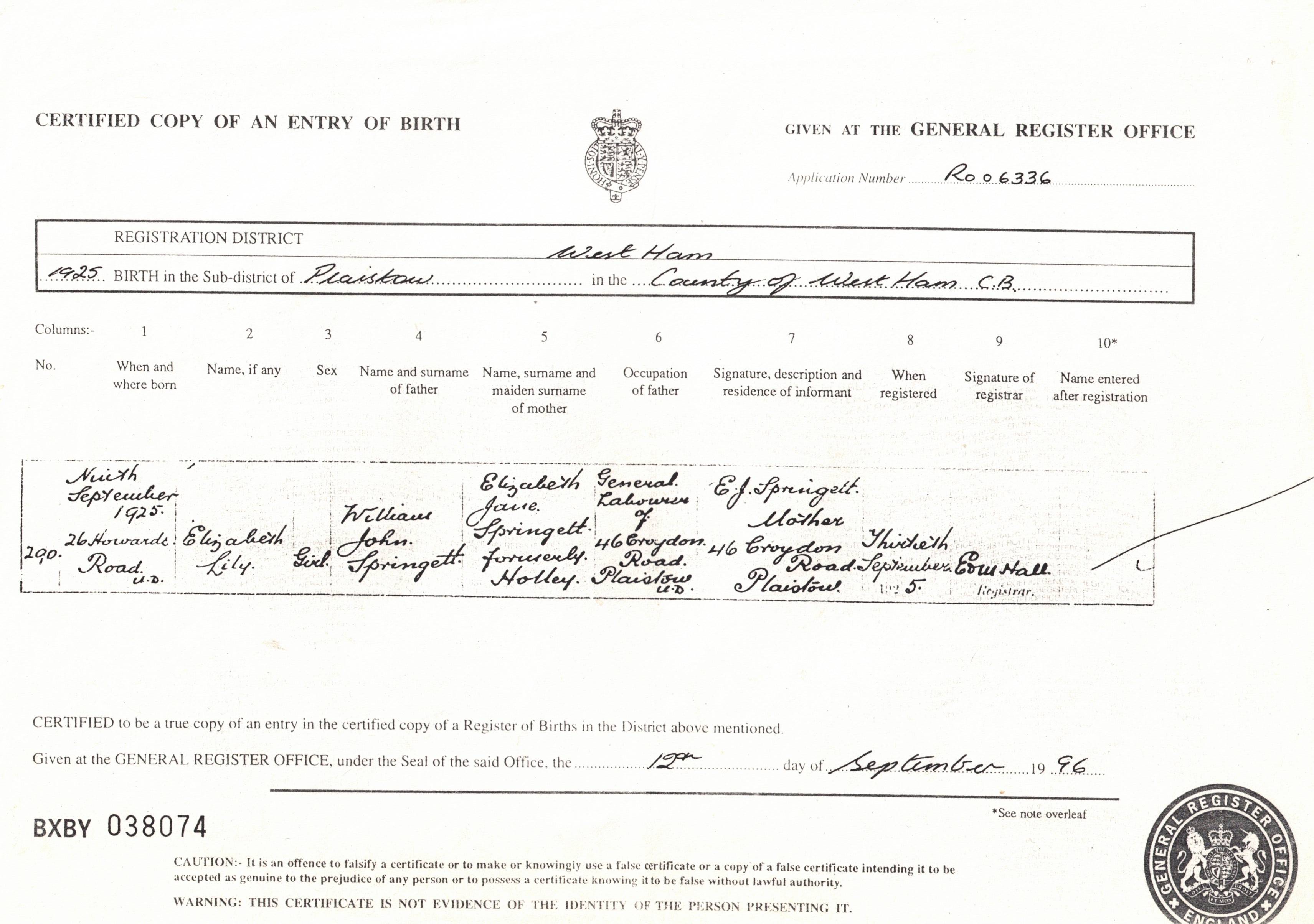

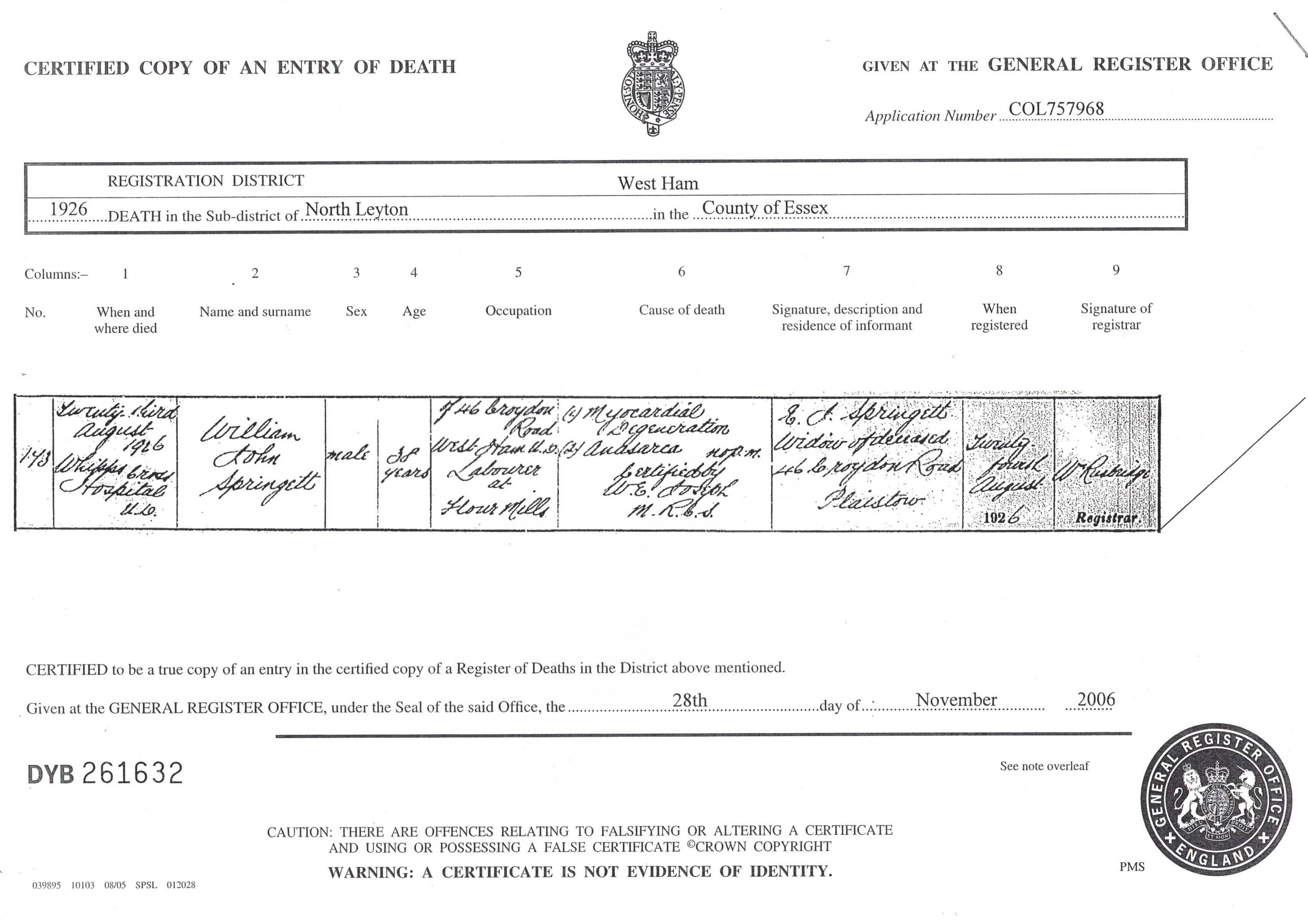

At the time of their marriage, William was recorded as a flour miller and living at 46, Croydon Road in Plaistow. They had one daughter, Elizabeth Lily Springett, who was born on 9 Sept 1925. But once again, tragedy was to strike Adelaide and her family.

(Birth Certificate for Elizabeth Lily Springett)

Almost a year after the birth of his daughter Lily, William, tragically died aged just 38, on 23 August 1926. He had suffered a heart attack. The family home was still 46, Croydon Road, in Plaistow.

(Death Certificate for William John Springett)

Once more Adelaide was alone, this time with no immediate family and only her decidedly unsavoury partner Frank Harling.

By 1927 the population of London had grown to 7.8 Million, an increase of 20% since the start of the century, making it the largest city in the world at the time. It was not just the largest city, it was also was home to the largest Port in the world. The inter-war years brought about a massive change in London’s landscape. Between the early 1920’s and 1940, almost 200,000 people were displaced from central and inner London, during a massive slum clearance program. Many of the courts and lodging houses that Adelaide and her family had frequented were demolished in the name of ‘progress’.

There are several electoral rolls that plot Adelaide and Frank’s movements through to their meeting each other sometime around the late 1930’s. Frank was with Elizabeth Verrion until about 1933 when he next appears on the electoral roll with Florence Matilda and her son Horace, all named Harling. They stayed together until 1938 when serial womaniser Frank and Adelaide’s paths must have crossed. Adelaide and Frank changed address about a number of times, before eventually settling in Ifield Road, Kensington, London

There are no known children from the relationship between Frank and Adelaide, which could have been for a variety of different reasons. It could have been due to Adelaide’s tough upbringing as a child, the lack of decent food or enough of it, the constant exposure to the elements, no permanent place of warmth or safety, the constant uncertainly of what the next hours or days would bring and the brutalising nature of life around her. It could of course have been that they chose not to have children, once again, questions that we cannot answer with any degree of certainty.

The 1946 electoral roll shows Frank Harling and Adelaide Ann Harling at 21 Cleveland Square, Paddington. An impressive and imposing building that was subdivided into flats.

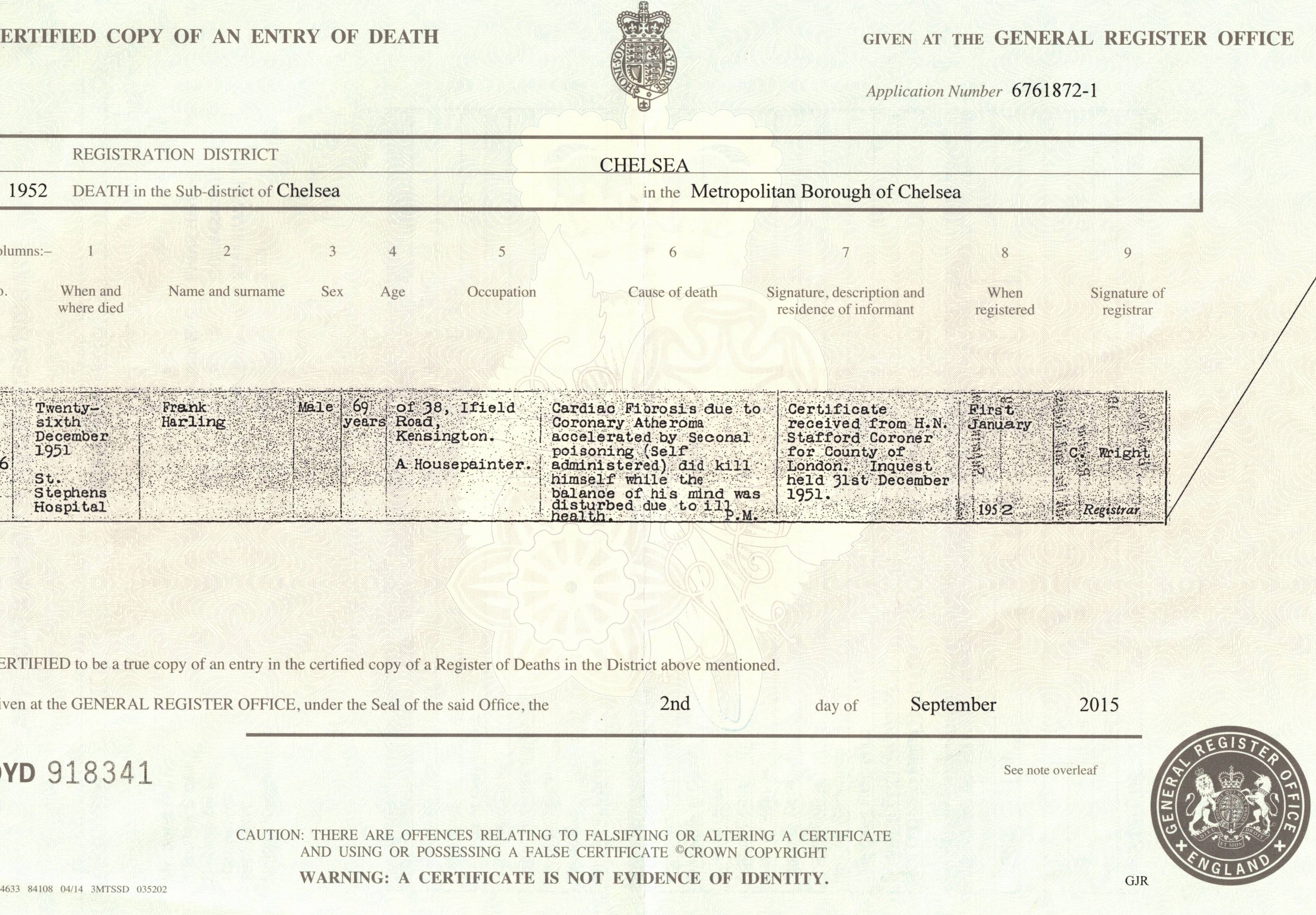

The next record that we find once more brings even more sorrow and chilling news. On Boxing Day 1951 her partner Frank Harling was to take his own life aged 69 years. The certificate records that he was a house painter of 38, Ifield Road, Kensington. I have so far been unable to find the record of the inquest, but the death certificate certificated by the Coroner leaves no doubt as to the cause. He committed suicide “whilst the balance of his mind was disturbed by ill health”. The reason of course can only be pure speculation and not for this blog.

(Death Certificate for Frank Harling)

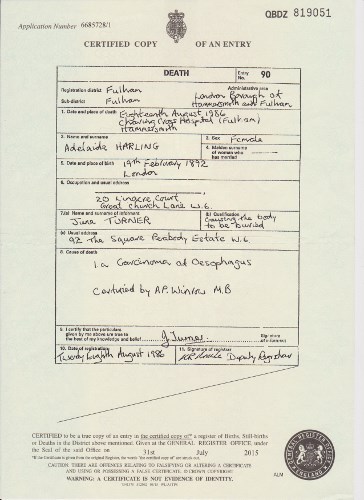

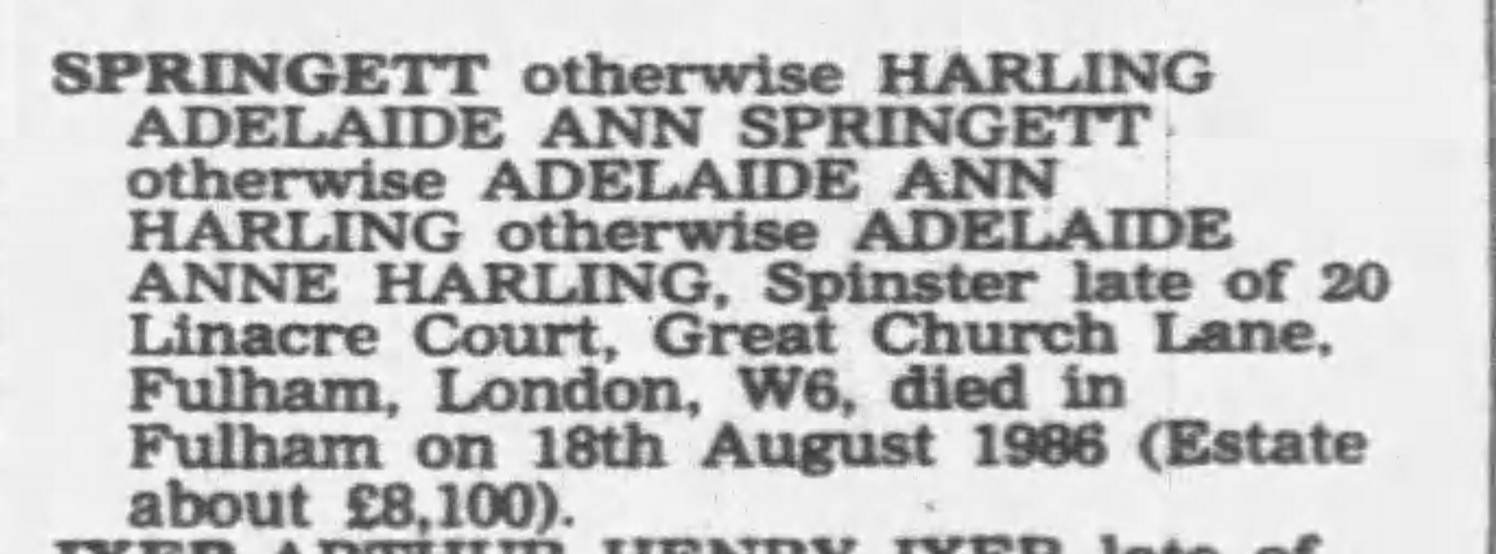

Adelaide was to live for a further 35 years, presumably alone, but she did keep the name ‘Harling’. She spent her final years living at 20, Linacre Court, Great Church Lane, Fulham, London. She died at the incredible age of 93 on 18 August 1986 in Fulham and at the time it was recorded that she had no traceable relatives. The London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Social Services Department were the executors of her estate.

Her life had been one of constant struggle, hour by hour, day by day, each moment wondering where the next meal was coming from and where the next warm shelter would be. I can see her face in the faces of the Dickens novels and like so many of her forgotten generation, she would never ever have enough of anything, food, warmth, shelter, love and above all else hope. I can see her face at the window and can’t help wondering if she ever thought back to those barefoot days in the dark alleys and courts of Spitalfields. A life that she was born into and couldn’t escape, a life where she was trapped by her own circumstances, with no escape, no hope and no future.

(Death Certificate for Adelaide Harling)

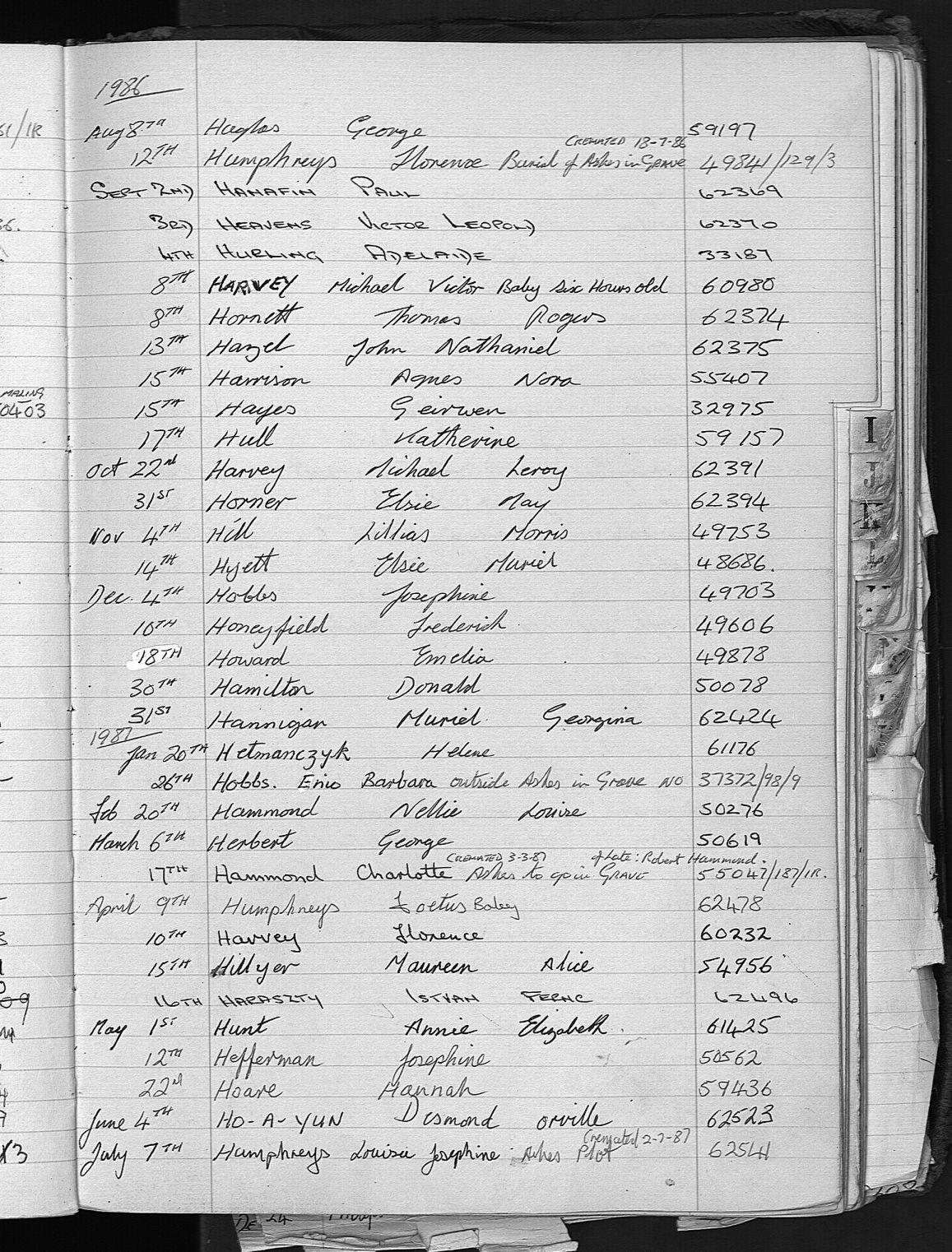

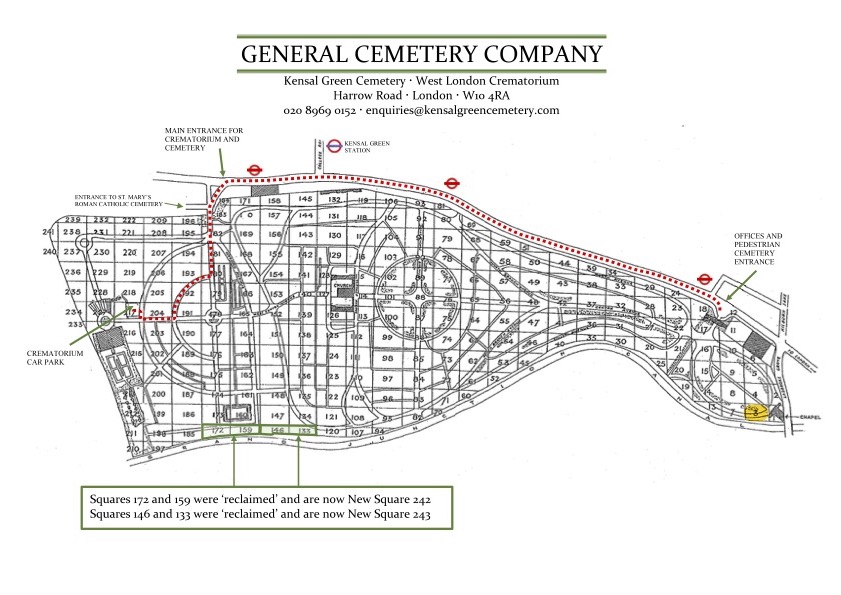

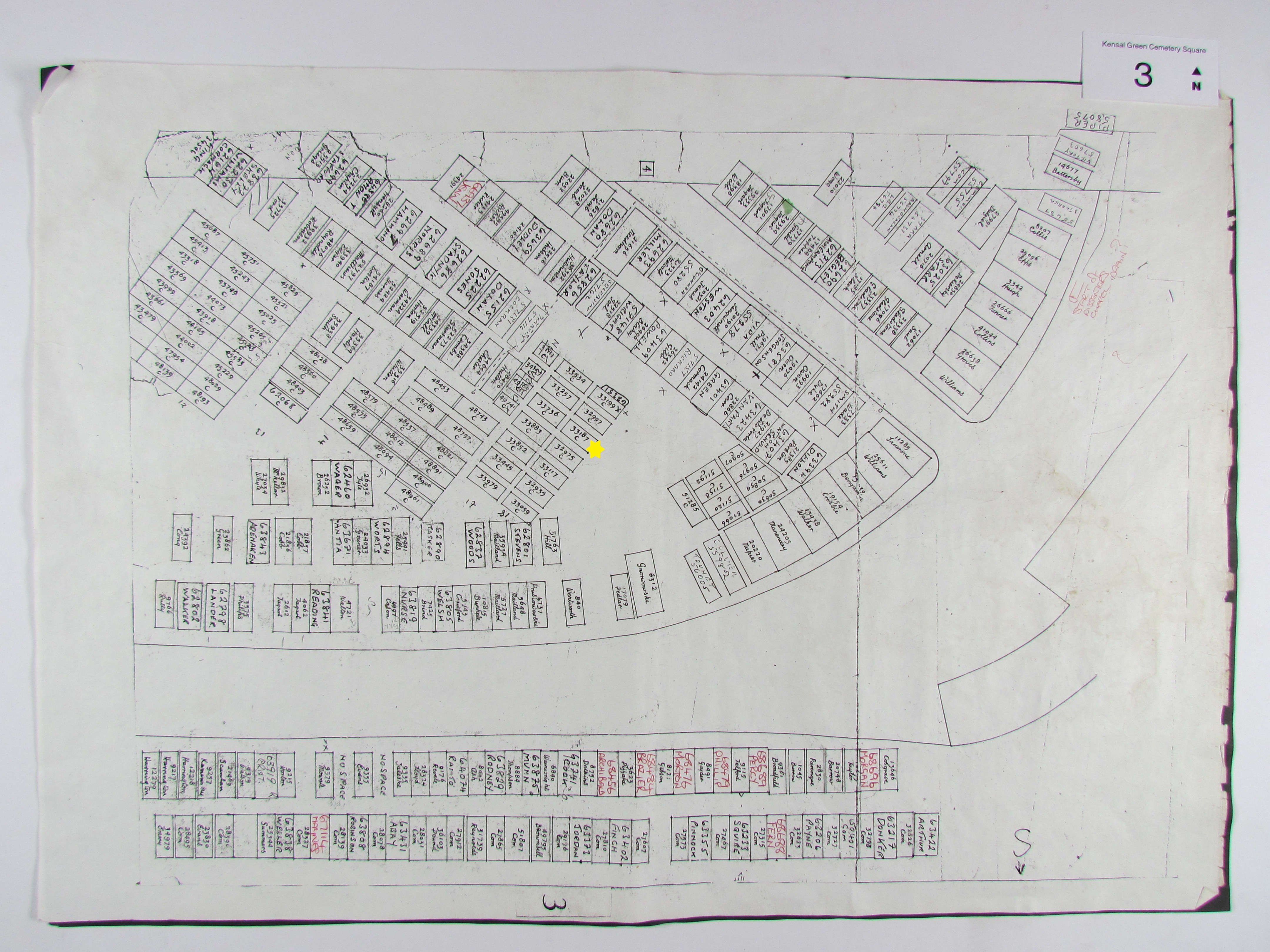

Adelaide was buried in a common grave (grave number 33187) at Kensal Green Cemetery on 4 September 1986. The location of the grave can be seen below on the map kindly provided by Kensal Green Cemetery. One day I will make a trip to London to visit and pay my respects to this little girl who has become such a big part of my life.

(Kensal Green Burial Register)

I hope that during the latter stages of her life, she found some form of happiness. I hope that she had friends and enjoyed the twilight years of her life. I want to see her smiling face enjoying the company of her friends and enjoying some laughter and pleasure for once in her life. The biggest thing that I hold onto the most, is that I hope that somebody was there with her to say goodbye.

From The Daily Telegraph London, dated Wednesday, February 18, 1987. One year after her death, there was a public notice of unclaimed assets from Adelaide Ann Springett’s (Harling) estate and her unclaimed assets went onto the bona vacantia list where contact was eventually made with Adelaide’s descendants.

At the time of her death, it was thought that Adelaide had died with no known living relatives, but that wasn’t the case, if you remember, Adelaide had a niece, a lady named Elizabeth Lily Springett and it was thanks to Elizabeth’s descendants that I was able to tell Adelaide’s story.

(Elizabeth Lily Springett)

With very special thanks to John Curno, the son of Elizabeth Lily Springett, for his extensive research and record keeping and of course for his love and dedication to his Great Aunt Adelaide. It’s with special thanks to John for allowing me to tell Adelaide’s story, which I hope will help to keep her memory alive and for that, I am truly indebted.

In loving memory of Adelaide Ann Springett, a poor young waif whose life was captured forever in that one moment by photographer Horace Warner. Her life was one of constant struggle against, poverty, deprivation and above all else survival. Her strength, bravery and courage to beat the odds and survive is a true testament to her character.

“Courage isn’t having the strength to go on — it is going on when you don’t have strength.”

(Adelaide Springett and friends)

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2024 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

Would love to read this, but the link is not working for me.

LikeLike

Adelaide sounds like a resilient woman…what a horrible life she led in her younger years. As you say, let’s hope after Frank’s death she found some stability and peace. Given his previous record, I can’t imagine life with him would have been easy.That photo is quite haunting…my family lived on some of those streets and at points, some distant cousins suffered some similar tragedies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Teresa she will forever live in my heart now and the important thing is that she will be forever remembered

LikeLike

lovely story Paul, thanks. Poor Adelaide, born two years earlier than my grandmother and died three years before her, but totally different circumstances. My gran was born into a rural middle class family, her grandfather was a police chief superintendent and later sheriff who set all his children up with homes and businesses, and her mother and aunts were the village publicans and owned several tied cottages. My grandfather, however, grew up near Spittalfields, was gassed out of the Somme and became a locomotive driver, meeting my gran on a trip north. Still, Adelaide survived, and maybe Frank had mellowed by his late 50s when they met, and she would have had a decent council flat and 70s pension in later years. By coincidence, my office in 3 Shortlands looked out on her Linacre tower block across the road when I was there in the 80s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Steve these stories and connections are forever entwined and I really do hope that Adelaide found happiness in her later years. The fact she endured such heartbreak and to go on to such a ripe old age is a testament to her strength and courage

LikeLike

Try this Moira https://chiddicksfamilytree.com/2024/02/15/adelaide-springett/

LikeLike

I was able to access the link and read your beautiful story of Adelaide. So well written and a perfect example of family history research that is so much more than just clicking on hints on a website.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so pleased that you was able to read Adelaide’s story and thank you so much for your kind words it’s very much appreciated

LikeLike

Couldn’t see the photo or rest of artic

LikeLike

Just amazing what this woman survived. You are kind to be keeping her name and memory alive so she will not be forgotten in the years ahead!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s such an amazing story and one that I felt compelled to share a testament to her strength and resilience

LikeLike

I have absolutely loved reading this, my Grandmother was born in 1895 and lived in Red lion Squste in Wapping, her Brother was born three years later and was serving in Salinonika (where he was killed aged 19) in the same regiment as Adelaide’s brother. In my mind I’m hoping they all knew each other

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lynsey I am pleased that you loved reading about Adelaide and her life. There is every chance that your grandmother and Adelaide’s families paths crossed, one hopes they would have looked out for each other

LikeLike

I have just filled in the contact form to send you a message regarding another blog you have written, the one on Great Baddow, hopefully you will pick it up and read it, a remarkable coincidence!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lynsey my email is chiddicks@yahoo.co.uk if you wanted to send it to me directly

LikeLike

Will do, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry about the spelling mistakes! Should have said Square and Salonika!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries I worked it out 😊

LikeLike

What a fascinating story! I only know of Victorian life from Charles Dickens’ novels and life of London’s poor obviously hadn’t improved at all in spite of his efforts to highlight their plight. However, little Adelaide must have had a strong will to survive such a terrible life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Linda it was such an amazing story and has taken months of research and I just felt compelled to tell her story

LikeLike

Wow, Paul – what a wonderfully researched article! Very poignant and such a sad story about growing up in exceedingly challenging circumstances. I can understand how hard this was to write – the tragedies in this family were numerous and never ending. Thank you for sharing this with the family history community.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Lynne it was such a difficult story to research and write. To do it justice I had to include all the difficult parts and not airbrush anything out. Adelaide holds a special place in my heart and she will always be a part of me now. You have to give a bit of yourself when you tell a story like this

LikeLike

You captivated me with the picture of the torn boots and the other photo with Adelaide in her bare feet. So many of these stories go untold … it would have been fabulous to interview Adelaide in her 90s!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I openly cried several times and had to stop work and take a break it was too emotional. Heartbreaking doesn’t even come close. I just need to know that she found happiness somewhere. There has to be some light in amongst all the darkness

LikeLike

My goodness, yes, it sounds like quite a journey you’ve been on with this research project. I’d hazard a guess and say that her happiness was in sheer survival and to make it to a ripe old age. Adelaide had what’s called ‘grit’ and that obviously saw her through life in her later years. I wonder if she was part of any seniors or museum society in her old age – they might have records or memories of her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Her strength and courage are to be admired to overcome everything that she had to endure is truly remarkable. Just surviving each day would have been a constant battle. I just hope that she managed to smile at some point in her life

LikeLike

What sent you on the road to telling this rich, thoroughly researched, sad tale? It’s incredible she lived to 93, given such a horrendous early life.

I’ve been watching the show “Call the Midwife” which is set in mid-20th century in the East End. Even though a later time period, it does give you some sense of how awful life in that area could be even then.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw her image online with those boots and was just drawn to her. At the time I had absolutely no idea where the story would take me! It’s been an emotional and incredible journey and like you say, I am sure that Adelaide’s life would have been so similar to many children at the time.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Not only an impressive story, but a durable record of Adelaide’s life, told in a thoroughly sympathetic and detailed manner. As a published genealogist, I am impressed with your approach, writing style, and attention to detail. Allen. Ottawa, Ontario.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind words Allen I appreciate that very much. I felt compelled to tell her story and she will be forever remembered

LikeLike

Fascinating story and amazing work!

LikeLike

Thank you so much Judith 😊

LikeLike

I’ve been haunted by Adelaide’s picture and story about her boots ever since I first came across it few years ago. I occasionally Google her which is how I found this article. Amazing that she reaped such a ripe old age. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Brian I’m glad you enjoyed the article and like you, Adelaide will always hold a special place in my heart now

LikeLike

Adelaide’s story is so moving and you paint a dark picture of what life was like for many in the East End. Thanks for sharing your great research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She will be forever remembered now and she will,always have a special place in my heart. Sadly her life would have mirrored so many other East End children at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure there are millions more stories like this ,of the families who struggled to survive the Victorian/Edwardian/WW1 area.Hard sad lives for them.It is always the poor and the children of the poor that suffer the most.It was nice to have a glimpse into just one of them.A couple of points though,her husband was obviously a disgusting person,withy nothing to “redeem” him.WHat he did was not “womanizing”- “Frank Harling pleads GUILTY to ‘carnally knowing Lilian Blanche Harling who was, to his knowledge his daughter’. He was se7ually assaulting his underaged daughter! Also ,I’m pretty sure the reason he and Adelaide had no children was not because of any of the reasons stated but simply because she was 54 years old when they met.And thank gods that they didn’t considering him past.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Peta for taking the time to read Adelaide’s story. I have said it many times before, but sadly her life would have mirrored the life of so many poor unfortunate children at the time. It’s always difficult to not make your own judgements and bias into a story especially given some of the circumstances that Adelaide faced. I think that we can all make our own judgements on Frank Harling, some of the words that spring to mind are not for printing. But Adelaide survived and moved on and lived an extraordinary life I just hope that she managed to find happiness somewhere

LikeLiked by 1 person

she would have been 44 or 45 (1893-1938), and he 11 years older, and they were together for 12 years to 1952. Still rather old for children though, let’s hope he had put his worst behaviour behind him and they were able to lead some kind of decent and companionable life, for her sake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did she know about his shady past? Probably not? I hope that he treated her better than some of his other women

LikeLike

would be interesting to try and reach out to people that had contact with Adelaide throughout her life and perhaps get some insight into what she was doing over the course of the years and what her personality was like.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am in contact with her only known relative and he was able to give some information about this but trying to find anybody else is going to be extremely difficult unfortuntalery

LikeLike

I’m heartbroken reading this story – I know there were so many like her, but her beautiful little face will be etched in my mind forever. I wish I could jump through the page and rescue her from that miserable existence. I pray she knew some happiness and security in her long life. Thank you for telling her story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing with me your thoughts Lisa. I pray and hope that somewhere in all that darkness there was some light for poor Adelaide I hope that she found happiness somewhere. She will remain forever etched in my heart now.

LikeLike

This is a touching story, came to the web page by searching Adelaide in one of the fb page under old London. Being to Spitalfild area when I was in London

Prageeth, Sri Lanka

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Prageeth appreciate your kind words thank you for taking the time to read Adelaide’s story

LikeLike

A very poignant read about hard times and circumstance of life in Victorian London, the poverty is obscene to our eyes now, and endless, with hope that the war would have brought about real change at home, but alas seemingly not. A wonderful story, if I can put it that way, of a beautiful child surviving the horrors of deprivation and the grind of every day, she survived well into the twentieth century, and I hope she found peace and happiness in her closing years, a story that shows just how close we are to out forebears and their lives, thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for taking the time to read Adelaide’s story and send me a message. Sadly her life would have been all too familiar to many Victorian children living in that area at the time. I can only hope that in her later years she found some kind of happiness its that thought that I have to hold onto. She will forever hold a place in my heart now.

LikeLike

I loved reading this. What I find most amazing is that Adelaide lived until her 90s, when she was brought up in such poverty with such lack of healthy food/ nutrients and accommodation rife with infections and bugs. She must have been made of such hardy stuff. Like you said I hope she enjoyed the last years of her life, in comfort.

Jane

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jane I’m pleased to hear you loved reading Adelaide’s story. Her courage and bravery shone through and it’s a testament to that, that she survived long into old age. I have to believe that she found happiness somewhere in her life.

LikeLike

I have added Adelaide’s grave as a (public) historical marker to Google Maps, for a future visit. I hope the tombstone still exists.

Thank you for sharing this extensive research!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Bravinsky much appreciated

LikeLike

Elizabeth Roberts 1898. Typo for 1889?

LikeLike

Elizabeth Roberts 1898 or 1889 typo?

LikeLike

I definitely have Elizabeth Roberts death as 1898

LikeLike

You say a year after Mary Jane Kelly (b. 1863-1888.11.9) was murdered.

LikeLike

apologies i can see what you mean now, the dates are correct, the twelvmonths is incorrect it is in fact ten years! Thank you for pointing this out for me, much apprecietd.

LikeLike

Do you have precise dates for Horace Warner (1871-1939) please?

LikeLike

Birth 19 JAN 1871 • Stoke Newington, London, Middlesex, England

Death 15 MAY 1939 • London, England

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome ☺️

LikeLike

It should be updated now to reflect the correction.

LikeLike

An extraordinary story, beautifully researched and sensitively told. Thank you. I have discovered that I have some Springetts among my ancestors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Shelly for your kind words I really feel so close to Adelaide now and she will forever hold a place in my heart

LikeLike

Horace Warner was my grandfather and I have his journal (unpublished)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Christopher I would love to make contact with you if I can my email address is chiddicks@yahoo.co.uk thanks Paul

LikeLike

Hi Christopher I would absolutely love to see Horace’s journal if that’s possible please drop me an email at

Chiddicks@yahoo.co.uk

LikeLike

Thank you for this wonderful monument. Many people deserve but never get.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Stephen much appreciated

LikeLike

what an incredibly sad but inspiring story, I was born and brought up in the east end myself, as was my parents, and their parents & ancestors before them, and listening to their stories, I understand a little of what this little one went through, tragic and sadly not the only one to go through some of what happened to her. My Dad not having shoes on his feet, youngest of 7, his mother dying at 42 in childbirth, his father having lost his sight, my Dad was 5, when his mum died. So many sad stories, but thank you so much for your investigative work, it was a pleasure to read, although so sad 💔

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Christina, I really appreciate your comments. My own grandfather was one of 16 children and never had his own bed until he got married. Adelaide holds a very special place in my heart and her story has now been told.

LikeLike

Such a heartbreaking story. Some great research here. Shows what you can uncover if you know where to look.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sarah, she holds a very special place in my heart now and it was a privilege to be entrusted to tell her story.

LikeLike

Brilliant warm human research very well written Cheers Arthur

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Arthur much appreciated

LikeLike

Brilliant warm human research very well presented & written Cheers Arthur

“All photographs are memento mori,” wrote American essayist Susan Sontag. “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely true!

LikeLike

Such a long, tragic life, filled with difficulties beyond imagining.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She holds a special place in my heart now Kym

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can well believe it. Funny how some people’s stories just touch you, even if they aren’t in your direct line. I find myself often wandering off to research some distant cousin’s life when I really should be concentrating more on the brick walls in my tree. Still, why else research genealogy if not for the stories?

LikeLiked by 1 person

For me it’s always about the stories I am a great believer in the fact that some stories find you. Adelaide is no relation whatsoever to me but her story came to me because it had to be told

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s it exactly! And thanks for subscribing to my blog, “Reading, Writing, Ranting, and Raving.” I might have some genealogy research stories on there, but most are on the blog I currently update, “The Byrd and the Bees” (https://thebyrdandthebees.wordpress.com). That is if you don’t mind weeding through stories about our bees and travels! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Kym I’ll take a look 👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

No pressure! I write on a variety of subjects, including genealogy and beekeeping. And I have to be honest, the beekeeping tends to take front seat in the summer, with genealogy being more a winter hobby.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s certainly an unusual interest but I do have a bee watering station in the garden so I’m doing my bit!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do they use it? Ours always like the dreckiest water around! Water is very important for honeybees!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very occasionally

LikeLike