The people of London lay blissfully asleep in their beds, completely unaware of the chaos and devastation that was about to unfold in the early hours of the morning. On a cold and rainy January morning in 1928, disaster struck the city when the River Thames flooded with devastating effect, claiming the lives of fourteen Londoners and leaving around 5,000 others homeless.

The floods were in part a man-made disaster and in part due to natural causes. Previous dredging of the Thames had made it easier for tidal surges from the North Sea to swell any high tides and on the night of the disaster, January 6th and 7th 1928, this tidal surge was added to by quickly thawing snow from further up the river. Of course, like all disasters, multiple contributing factors came together with tragic and devastating consequences. Leading up to this event, Christmas 1927 saw heavy snowfall further upriver, near the river source, in the Cotswolds, and when this snow melted, in early January 1928, it was reportedly said that the sudden thaw doubled the volume of water in the Thames, adding to the already swollen River. This sudden and rapid thaw made the subsequent impact of the storm surge even worse. The Thames reached its highest recorded levels, with a reading of 18 feet 3 inches above the datum level at around 1:30 a.m. on January 7th, setting a new record at the time.

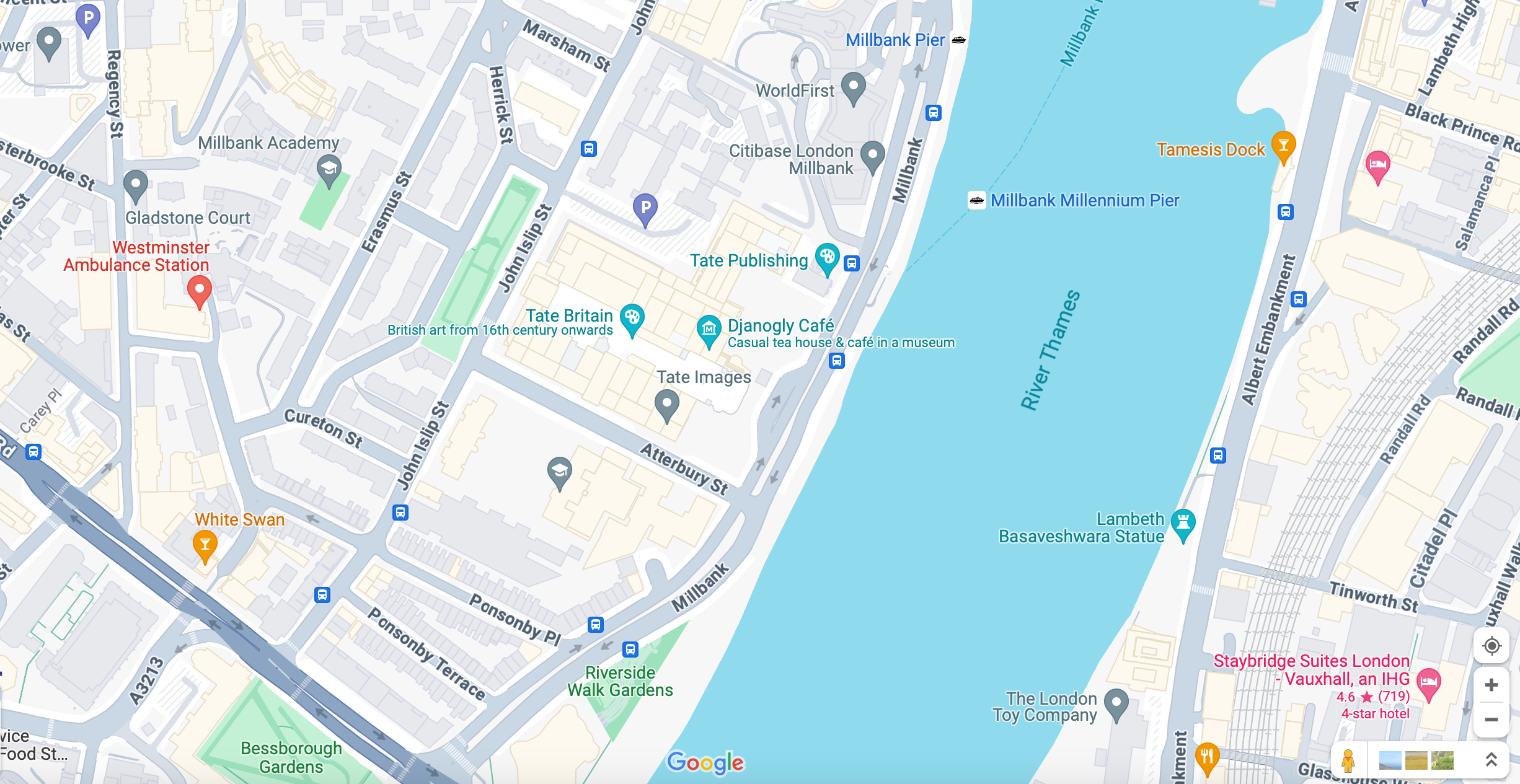

The results of this perfect storm were obvious, from the City and Southwark in the east, to Putney and Hammersmith in the west, the Thames burst its banks, overflowing those protective walls that had been put there by nineteenth-century engineers to contain it. The first section of the riverbank to give way was opposite the Tate Gallery, where a 75 ft section of the Embankment collapsed. There was also widespread flooding in central London, including at the embankment by Temple Underground Station. Around Lambeth Bridge, large parts of the embankment washed away altogether, allowing a wall of water to race through Westminster’s and Lambeth’s slums. In total, in the course of just a few hours, fourteen people died, all of them unsuspecting inhabitants of basement flats, who were drowned in their sleep. Some 5,000 others were also rendered homeless. Areas around the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Hall were flooded and unbelievably, the moat around the Tower of London also filled. HMS President, the Royal Naval Training Ship which was permanently moored by the Victoria Embankment was seen floating majestically along the Embankment before being temporarily anchored by Cleopatra’s Needle! The Blackwall and Rotherhithe Tunnels were also flooded as Londoners witnessed scenes of devastation across the whole City.

The two short video clips below give a brief insight into the devastation left behind in the aftermath of the flood. These videos capture the true scale of the disaster and the destruction left in its wake

The Great London Flood of 1928

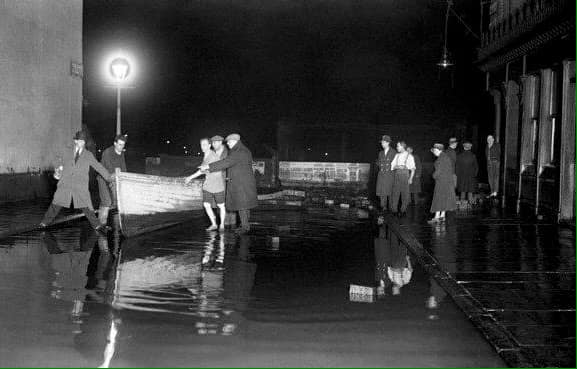

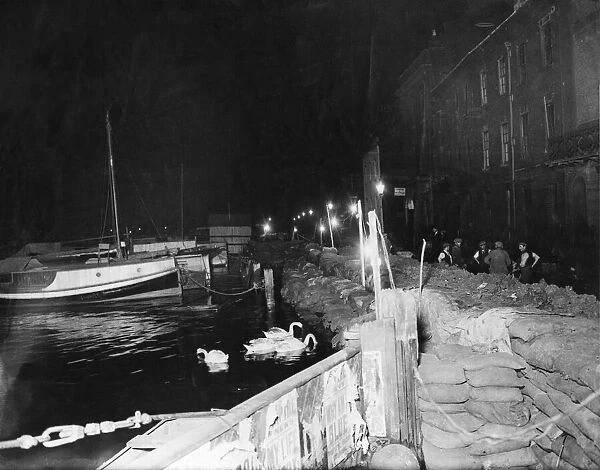

As well as the two video clips, there were numerous images captured of the disaster and below is a selection of images that show the real damage and force caused when the River burst its banks.

(Image: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

(Image: Print Collector/Getty Images)

(Image: Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

The damage was immeasurable, but at the heart of this story however are the people, it was the human element and the loss of life that had the most devastating effect, as fourteen people, who were peacefully asleep in their beds one minute, were tragically drowned within minutes.

In Putney; Irene Watson and her cousin Dorothy Watson died aged just 23. They were sleeping in a basement flat in Hurlingham Court in Putney and were trapped when the river burst through the Hurlingham Club banks. As with all disasters of this magnitude, there were also tales of heroism. There would have been more deaths except for the bravery of their friend, Madge Franckeiss, who was staying in the flat with them. She rescued Mrs Watson, the mother of Irene, and her son Billy, swimming for over an hour in the pitch darkness, in and out of the rooms in the flat, in the bitterly cold and filthy Thames water as it reached nearly to the ceiling. She eventually had to stop as her feet and legs were badly cut and she was taken to Fulham Hospital. The coroner, concluded after the inquest into the deaths of Irene and Dorothy Watson, that having heard her account, two more people would have died without her actions and he praised her “coolness, courage, resource and presence of mind”. The Mayor of Fulham, Alderman W J Waldron, opened a testimonial fund in recognition of Madge Franckeiss’ bravery and there was a generous response from all parts of the country. The short clip below shows Madge Franckeiss outside Fulham Hospital.

The beautifully illustrated citation below described the rescue and was awarded to Madge Franckeiss.

Madge was later awarded an inscribed Gold Watch by The Carnegie Hero Fund Trustees, plus a Bronze medal from the Royal Humane Society.

In Hammersmith; Annie Moreton 23 and Evelyn Hyde aged 20, also died, servants who shared a basement flat at River Court Upper Hall, Hammersmith. A separate hearing and inquest into their tragic deaths heard how the two domestic servants drowned in similar circumstances in a room they shared in Hammersmith. The coroner, Mr HR Oswald, said they had been “caught like animals in a trap drowned before they realised their position”.

The biggest loss of life, however, was In Westminster where ten people drowned; Four sisters, Florence Emily Harding aged, 18, Lillian Maude Harding, 16, Rosina Harding, 6 and Doris Irene Harding, who was only 2 years old, who lived at 8, Grosvenor Road, Harry Sears, aged 17, of 1, Horseferry Road, Mrs Sarah Quick aged 63, of 30, Causton Street, Nellie Hinchley aged 32 of 22, Grosvenor Road, Frank Willsher aged 25, of 21, Hinchcliffe Street, Lilian Jones aged 16, of Grosvenor Road and Jane Hawley of Vincent Street.

Tragically in total six people lost their lives in what is now Millbank, but was then known as Grosvenor Road, when the murky water rushed through the narrow streets that led from the river, gushing through the century old tenements. The area of Westminster between Grosvenor Road, Horseferry Road and Vincent Street was severely affected. The Ministry of Health estimated at the time that of the 600 families who lived in the area before the flood, that over 500 families needed to be rehoused. Unfortunately the early 19th century housing appears to have had been built on low lying marshland adding to the vulnerability of the residents in 1928, many of the fatalities of the flood had been residents living in houses built almost a hundred years earlier. The impact of the flood was profound. A major slum clearance, re-housing and re-building plan was undertaken over the next few years to create some of the most iconic buildings in the area including Thames House, a new Westminster Hospital in Horseferry Road along with a new Lambeth Bridge and the widening of the river embankment and the creation of Millbank.

Every single one of those fourteen deaths was tragic and the loss felt deeply by the families, but it was the loss of four sisters together that struck a chord with me and I felt immediately drawn to their story and their plight. So who were the Harding family and what was their story?

The four sisters that tragically drowned were part of a much larger family consisting of ten children born to parents Alfred William Harding and Eleanor May Streatfield. Alfred was born on 12 August 1881 in Islington in London and Eleanor was born on 16 June 1885 in Bloomsbury in London and the couple were married on 31 July 1904 at All Saints Church, Battle Bridge, Caledonian Road, in Islington, North London. Alfred’s occupation was a Cab Washer and neither of the couple had been married before. At the time of the marriage they gave their home address as 11, Wynford Road in Islington.

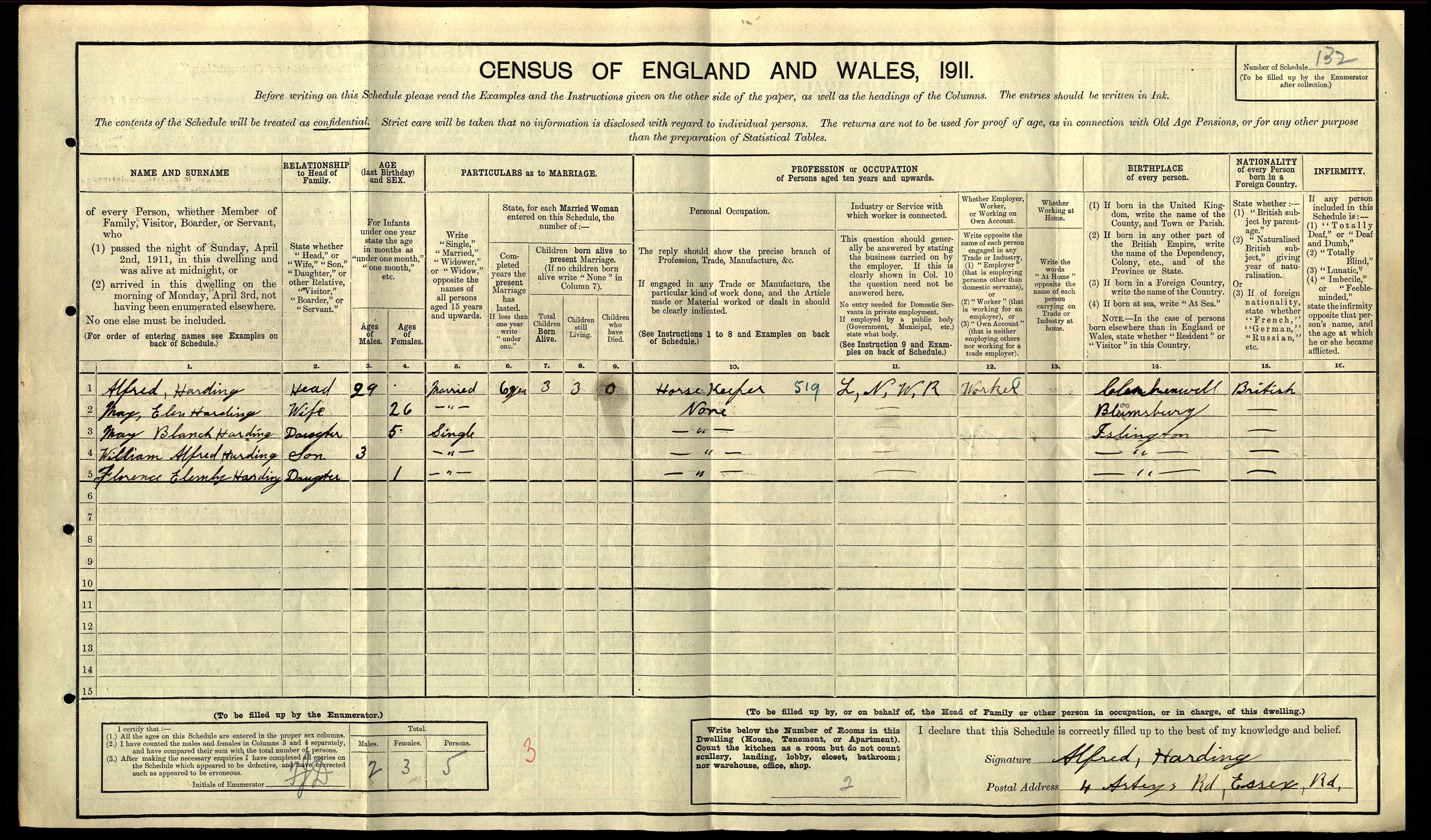

The 1911 census shows the family residing at 4 Asteys Row, Asteys Road, Essex Road, North Islington, Alfred is recorded as a Horsekeeper with the London and North Western Railway. At home with Alfred and his wife Eleanor May were three of the children, May Blanche 5, William Alfred 3, and Florence Emily 1.

(The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911)

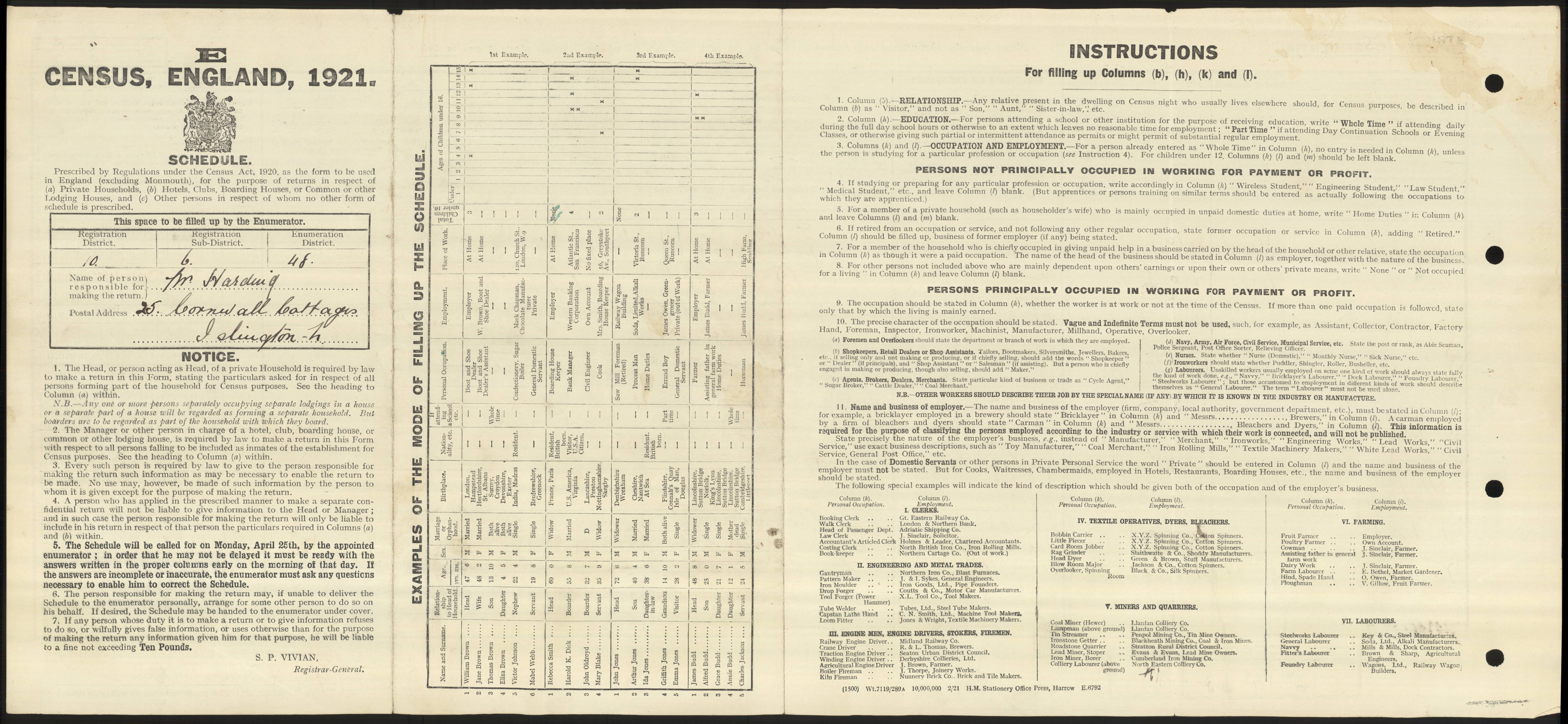

1921 Census records the family living at 25 Cornwall Cottages, North Islington in London and Alfred and May Ellen Harding are living at home with seven of their children, May Blanche, 15, William Alfred 13, Florence Emily 11, Lily Maude, 8, Alfred Henry 6, Frederick Ernest 4 and young Rosina Gladys aged 1. Alfred is employed as a labourer with Holland, Hannen and Cubitts, Builders of Gray’s Inn Road in London. In 1922 they won the contract to build the new County Hall in London, something that Alfred would have most likely worked on. Little did the family know what was waiting for them just around the corner. Just six years later disaster was to strike the Harding family with such a devastating effect.

(The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; 1921 Census Returns; Reference: RG 15/1009, ED 48, Sch 25; Book: 01009)

At some point between 1921 and 1928, the Harding family moved from North Islington to the riverbank in Westminster when they took up residence at 8, Grosvenor Road (Now Millbank) and it was the family’s close proximity to the bank of the Thames that ultimately was to cost them dearly.

The tragedy in all of this is the fact that it was the families poor living conditions that added to their already difficult plight. Westminster was hit particularly bad with the Embankment washed away completely, allowing a wall of water to race through the narrow streets, courts, alleys and crowded basements with devastating effect. The images below, taken a few days after the tragedy struck, shows how the waters churned up the surface of Grosvenor Road.

As you can imagine, the newspaper reports about this event are aplenty. What happened is pretty well documented but it is the human element in all of this, not only the cost of human life, it’s the aftermath. How does a family like the Harding family recover from such a devastating loss of four children in one night?

I have included just the one newspaper report here, amongst the many that were published at the time. This report is rather a harrowing read and details the eye witness account of the father of the four Harding sisters who tragically drowned. Taken from the London Weekly Despatch dated 8 January 1928.

4 Sisters Trapped in Basement

ORDEAL OF FATHER.

“OPEN THE DOOR!”

CRY OF AGONY.

NO CHANCE.

Pathetic descriptions were given yesterday of the tragic fate of four girls trapped beyond hope of rescue in a front basement. This was a poignant result of the night of terror and tragedy which befell those in the Westminster area on the north bank of the Thames between Lambeth and Vauxhall Bridges. Havoc in this area was tremendous. The spot where the river broke through looked as if it had been struck by a tidal wave. Masses of stone weighing many hundredweights, forming the top layer of the parapet, were torn clean away and carried half-way across the road. The river broke down the parapet in several places and swept in a raging torrent along Grosvenor Road, Horseferry Road, Causton Street, Ponsonby Place, and other streets, entering scores of houses.

So sudden was the calamity that most people got their first warning when the water poured into their houses, while a Constable on point duty at the end of Horseferry Road was forced to run for his life. Several people who gave the alarm were swept off their feet. In all, the bodies of ten people were taken to Westminster Mortuary. They were; Florence Harding 18, of 8, Grosvenor Road, Westminster and her three sisters, Lilian aged 16, Rose aged 6, Doris aged 2 ½, Nellie Hinchley aged 32 of 22, Grosvenor Road, Lilian Jones aged 16, Frank Willsher 25, of 21, Hinchcliffe Road, Harry Thomas Sears aged 17, Mrs. Quick aged 63, and Jane Hawley of Vincent-street. The four Harding sisters lived with their father, who has four other children, at 8, Grosvenor Road, a small terrace house abutting on the river opposite Lambeth Bridge. The bereaved father graphically described the story of their fate in an interview yesterday. He said:

“These four girls were sleeping in the front basement kitchen. I only moved them down there from a bedroom on the top floor a few days ago because it was warmer. I was awakened by a noise in the morning, and thinking it was the workmen down below, I got out of bed. But no sooner had I opened the front door than the water rushed in. There was absolutely no warning. I did not stand a chance. I ran downstairs and tried to open the kitchen door, but the door opened inwards and the pressure of the water was too great. My four children were inside. I could hear my daughter Lilly crying, ‘Dad! Dad! Open the door!’ But I was powerless to help them. The water at that time was up to the top of the door. I dived down into the water, but it was of no use. There were iron bars in front of the window so that the children could not get out that way. Lilly, the 16-year-old child, was a fine swimmer and had won about 20 certificates. If she had had a chance to get out, she could have swum free. If I could have got the door open the water would have found an outlet along the passage, but I could do nothing, and the children were completely trapped. Mr. Harding added that although heroic attempts were made by neighbours, the girls were caught and drowned in something under twenty seconds. When they got at them, they seemed to have died without a struggle. When the protecting wall of the Embankment gave way with a loud noise. a mass of water came across the road and entered the house practically without any warning.”

It was years before all the damage was eventually repaired and despite this tragedy, it took a further flood in 1953 to persuade the Government to look at building a Thames Barrier which was finally completed in 1982, some 54 years after the 1928 disaster. A documentary entitled 1928: The Year the Thames Flooded is available on Channel 5 and tells the whole tragic story;

Watch it online here on the Channel 5 website.

This story is written ‘In Loving Memory of the fourteen poor souls who tragically drowned in the 1928 Thames Flood’.

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2025 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

I had no prior knowledge of this shocking event. An interesting and informative piece, well researched but ultimately very sad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sheree like you I was unaware until last year hence why I carried out the research

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a horrific event and the loss of life was extremely sad. Thank you for exploring the lives of those affected by the tragedy and spotlighting heroes like Madge!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Marian it’s always the people behind the headlines that matter the most

LikeLike

Wow – I had no idea about this…my family was fortunate, living further from the river. Such a terrible event with heart-breaking consequences.

LikeLike

What a tragedy! The eye-witness account of the father of the Harding girls was so moving. Nearly 100 years later, it’s good to remember them and the other victims.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know his account is truly harrowing you can’t imagine what he went through as a father. It would have haunted him for the rest of his life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, what a terrible night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What Ann interesting article. Unimaginable horror.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you such a harrowing story

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing this story, Paul. I only knew about this flood before very vaguely. I appreciate that you have looked into the Harding family – what a terrible tragedy for one family to bear.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a father myself, I just can’t imagine what that poor man went through, truly awful.

LikeLike