From the Banks of the Thames to the Mud of Passchendaele: The Life and Loss of Harry Joseph Keyes

Before the mud, the gunfire, and the chaos of the Western Front, before the thunder of artillery at Ypres silenced his young life, Harry Joseph Keyes was a boy growing up in the heart of working-class Edwardian England.

On a late summer’s day on 30 August 18911 in the riverside town of Grays, Essex, young Harry Joseph Keyes was born into a world on the cusp of a new century. He was the seventh of eight children born to Joseph and Elizabeth Keyes (née Bishop) and was born at home at 28 Prospect Row, in Grays, Essex2. His arrival came at a time when Britain was at the height of its imperial power, yet life for families like the Keyes household was shaped less by empire and more by daily endurance, community, and hard labour. Joseph, Harry’s father, worked as a labourer in the local cement industry, a physically punishing job, typical of the area, where industrial growth had taken firm root along the banks of the Thames. Elizabeth, his mother, managed the large household, raising eight children in modest surroundings.

By the time of the 1901 Census3, the family was living at 28 Prospect Place in Grays. Evidence from analysing the two census returns side by side points to this being the same address as 28 Prospect Row, it was just a name change. It was a town defined by its industrial landscape: looming cement kilns, smokestacks, chalk pits, and the constant rumble of carts and barges along the nearby docks. The cement industry dominated local employment, shaping the lives of thousands of families in Thurrock. For children like Harry, this gritty, grey-toned world of dust and machinery formed the backdrop of their earliest memories.

The following images were kindly donated by Dylan Moore from his wonderful historic site of Cement Kilns Works in the UK.

Though no school records survive for Harry, he likely received a basic elementary education. By the late 19th century, the Elementary Education Acts had made school compulsory for children up to age 12. Working-class boys were taught reading, writing, arithmetic (the three Rs), and moral discipline, an education designed to prepare them for a life of labour rather than scholarly pursuit. It was not uncommon for boys to leave school early to begin earning wages, especially in large families where every contribution mattered.

By 19114, Harry was 19 and, like his father, working as a cement labourer. The family had moved to 57 Stanley Road, still in Grays, and Joseph, now ageing, had taken up work as a night watchman, a less physically demanding role secured after decades of toil. For Harry, there may have been little question of his path. In a town like Grays, a young man’s future was shaped more by practicality than ambition. His life followed a familiar pattern for working-class men of his generation: school ended early, work began young, and the future was defined more by endurance than ambition. He would have known the value of resilience long before he ever wore a uniform.

The world was changing rapidly, and in August 1914, war erupted across Europe, drawing Britain into a conflict that would soon engulf the globe. The First World War, with its web of alliances, industrialised killing, and unimaginable scale of loss, would soon touch every corner of British society. Towns like Grays, where patriotism ran deep and service to King and Country was seen as a solemn duty, felt the call keenly. A wave of fervent nationalism swept the nation, posters lined the streets urging enlistment, bands played rousing tunes in town squares, and recruitment offices overflowed with young men eager, or compelled, to do their part. For a generation raised on ideals of duty and Empire, answering that call seemed not just expected, but honourable. Among them was Harry Joseph Keyes.

For families like the Keyes, the years ahead would bring hardship, separation, and sorrow. The age of innocence was ending, and a brutal new chapter of history was beginning, one that would reshape lives in ways previously unimaginable. At some point during the early stages of the war, Harry responded to that call. His military records suggest he may have joined under the Derby Scheme, a system of voluntary enlistment with delayed service, or he may have been conscripted under the Military Service Act of 19165. In either case, it’s believed he formally enlisted in March of that year. As an unmarried man in his mid-20s, Harry belonged to the group most commonly drawn into service, young, able, and, like so many others, swept up in the defining struggle of his time.

Initially, Harry was assigned to the Essex Regiment, his home County Regiment, with the regimental number 49016. Later, he was transferred to the Gloucestershire Regiment, receiving a new number: 235186. His medal records, which include the British War Medal and the Victory Medal7, confirm he did not see active service abroad until after January 1st, 1916. In fact, it wasn’t until June 16th, 1917, that he embarked for France, part of a draft from the Essex Regiment. Upon arrival in Calais, he was recorded ‘for administrative purposes’, with the 10th Essex Regiment at the 15th Infantry Base Depot. Shortly after, on 7 July 1917, Harry was posted to the 1/4th (City of Bristol) Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, part of the 144th Brigade, in the 48th (South Midland) Division. He joined his new battalion in the field on 10 July 19178. The war diary records a significant intake of reinforcements that month, 280 other ranks, including Harry, and alongside his colleagues, he began preparing for what would become one of the bloodiest periods of the war, the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as Passchendaele.

(Picture taken from my collection from my visit to The Western Front in July 2025)

Harry’s battalion did not take part in the early assaults of the campaign. During August and September 1917, they rotated in and out of reserve and training camps, avoiding the full brunt of the attacks at Langemarck and Polygon Wood. Harry may have served as a stretcher-bearer or prisoner guard during the engagements at Broodseinde on 4 October. These roles, though less glamorous than front-line assault, were no less dangerous; sniper fire, artillery, and the relentless mud defined every job on the battlefield.

The picture below shows ‘Hellfire Corner’, along the Menin Road. At the time this was taken it was known as the most dangerous corner on Earth.

(Picture taken from my collection from my visit to The Western Front in July 2025)

In early October 1917, the 1/4th Battalion was called forward to participate in the Battle of Poelcappelle, a phase of the larger and infamous Third Battle of Ypres, better known as Passchendaele. The offensive had dragged on for months through relentless shelling, flooding rains, and nightmarish mud. By October, the ground had become a mass of cratered fields, flooded dugouts, and barely passable duckboard tracks. Casualties were staggering, and conditions on the battlefield were beyond appalling.

Extensive War Diaries exist for the 1/4th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, covering the period leading up to and following the attack in which Harry tragically lost his life on 9 October 19179. These records provide valuable insight into the events surrounding that day and the conditions faced by the battalion. I have included an extract that shows that the commanding officer had to submit a comprehensive and detailed report to his superiors, outlining the sequence of events that transpired.

(The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; First World War and Army of Occupation War Diaries; Class: WO 95; Piece: 1265)

On 9 October 1917, Private Harry Joseph Keyes took part in the Battalion’s assault during the Battle of Poelcappelle. Harry’s battalion was part of an ambitious Allied push up the Poelcapelle Spur towards Westroosebeke. Their approach through the shell-churned terrain, made worse by days of rain, was delayed and disorganised. The plan involved a night march to the jumping-off point near ‘Tweed House’, but the approach was confused and chaotic. The darkness, mud, absence of guides, and heavy packs led to lost companies and delays. Lieutenant-Colonel John Crosskey, the Battalion’s commanding officer, personally led what men he could gather through the desolate terrain. They arrived at the start line just minutes before the creeping barrage began at 05:25

The map below shows the position of both front lines prior to the attack taking place and shows the location of the village of Poelcappelle, just north east of Ypres.

(Picture taken from my collection from my visit to The Western Front in July 2025)

Harry’s ‘A’ Company, alongside ‘D’ Company, led the attack. They advanced through a storm of machine-gun and sniper fire, bogged down by exhaustion, poor visibility, and sodden terrain.

The attack struggled almost from the first step. The creeping barrage advanced too quickly for the men to follow in the quagmire, and they lost its protection. The battalion was raked by fire from German machine-gun nests in the ruins of Oxford Houses, Beek Houses, and along the hedge lines of the battlefield. Isolated groups of brave men pushed forward under near-suicidal conditions, some establishing temporary positions in shell holes, only to be forced to fall back later due to heavy counter-barrage and withering fire. The chaos of the day was compounded by the difficulty of moving wounded men under sniper fire; stretcher bearers were particularly targeted by the enemy.

The following quote was mentioned to me by Glenys Sykes (https://wordpress.com/reader/feeds/157596970) and is taken from a book called ‘Fields of Battle’ by Michael St Maur Shell. The quote is taken from the diary of Leutnant Schafer (Infanterie-Regiment 465) and is extraordinarily poignant. It reads:

“From a small pill-box I have a good view over the battlefield. In front of me is a remarkable sight: a break in the battle to remove dead and wounded. The guns are silent, a deep peace rules over the battlefield. No plough could gouge the fields in such a manner. The chaos is awful to behold. Slowly and carefully, stretcher-bearers with dogs arrive from both sides. Friends and foe alike have their red crosses clearly displayed. Fascinated, I watch this sad task through my field glasses.What a difference: no will to hurt, no raw hatred, just pure humanity.”

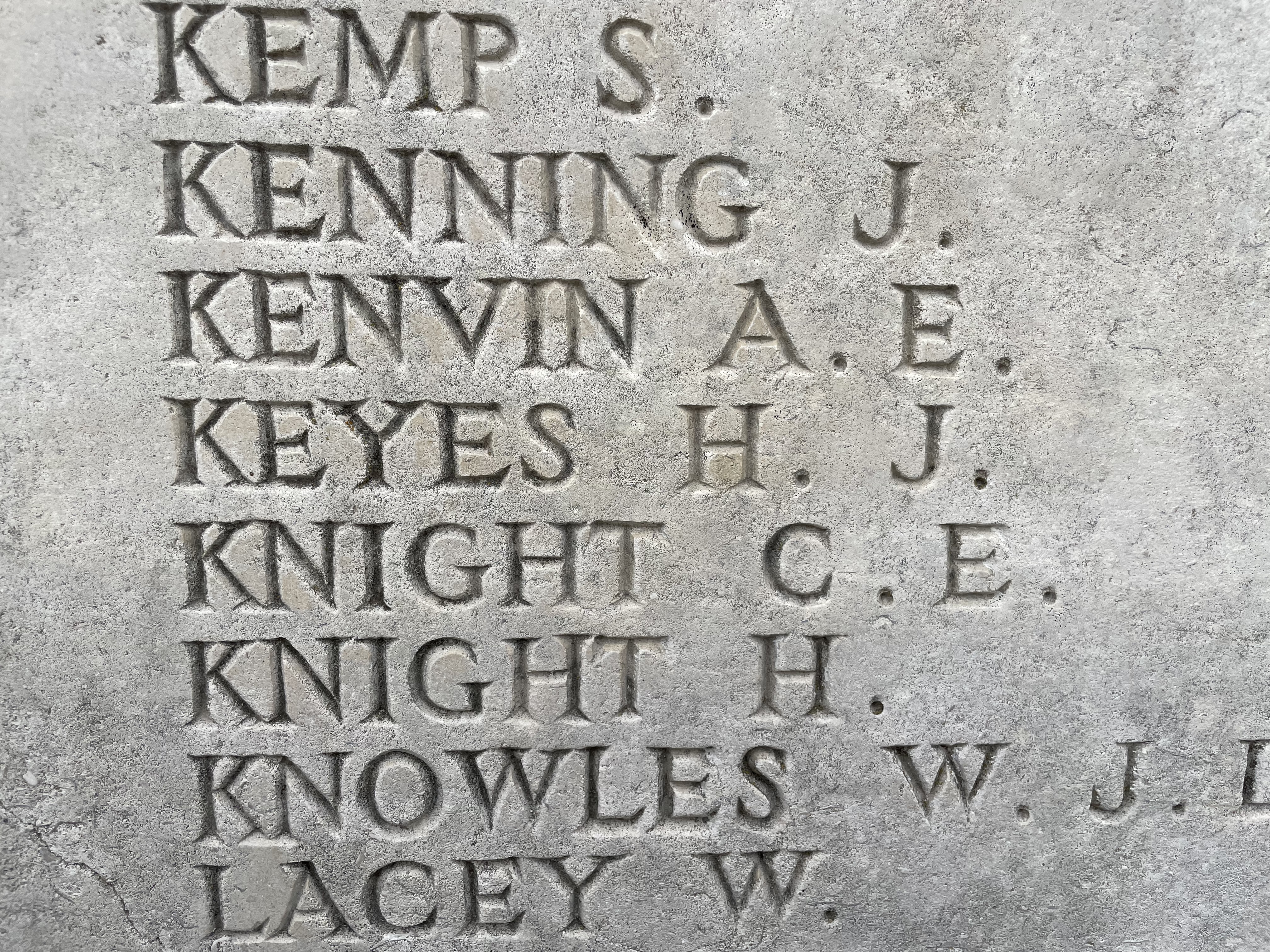

The Battalion suffered 177 casualties that day. Sixty-nine men were killed, among them Private Harry Joseph Keyes, aged just 23. His body was never recovered or identified, and he is commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial, Panel 74, among the tens of thousands of soldiers with no known grave.

In July 2025, I was able to visit the Western Front and pay my respects to ‘Uncle Harry’ in person at the Tyne Cot Memorial.

(Pictures taken from my collection from my visit to Tyne Cot in July 2025)

The Keyes family had felt the profound and heartbreaking impact of the War. Three of the Keyes sons bravely enlisted to serve their country, but tragically, only two would return home. Albert George Keyes served with the 2/8th Essex Cyclists and survived the conflict, as did Bertie James Keyes, who served in the Royal Air Force. However, the family’s joy was overshadowed by the heartbreaking loss of Harry Joseph Keyes, who fell in battle on 9th October 1917.

Harry’s death was a devastating blow that shook the entire Keyes family to its core. The grief was so overwhelming that, barely a month after receiving the tragic news from the front line, Harry’s mother, Elizabeth Keyes, passed away on 3rd November 191710. It’s believed that the sorrow and heartbreak she endured following the loss of her son contributed significantly to her untimely death. Harry had gone to serve King and Country with honour, but his sacrifice left a permanent and painful scar.

Today, Harry’s name endures on a memorial far from Essex, and in the hearts of descendants, like me, who continue to tell his story, a story of a young man who left the cement yards of Grays, for the fields of Flanders and never came home. He was one of countless young men whose lives were shaped and ultimately cut short by the First World War. But behind the uniform, he was more than a soldier. He was a son, brother, grandson, uncle, nephew and part of a family who carried on without him but never forgot him.

In remembrance of Harry Joseph Keyes, a fallen soldier, a young man whose quiet dreams never had the chance to be fulfilled. In telling his story, we honour all those who served, and we ensure that their names are not lost to time.

Also in remembrance of his mother, Elizabeth Keyes,

who passed away on 3 November 1917.

May they rest together in peace, forever remembered.………….

Sources

- England, birth certificate (certified copy) for Harry Joseph Keyes, born 30 Aug 1891; registered September quarter 1891, Orsett Registration District reference 4A/427 ↩︎

- Address as noted on his birth certificate: England, birth certificate (certified copy) for Harry Joseph Keyes, born 30 Aug 1891; registered September quarter 1891, Orsett Registration District reference 4A/427 ↩︎

- 1901 England and Wales Census Class: Class: RG13; Piece: 1660; Folio: 14; Page: 19 ©Crown Copyright / The National Archives. Accessed via Ancestry 1901 Census ↩︎

- 1911 England and Wales Census Class: Class: RG14; Piece: 9975; Schedule Number: 288 ©Crown Copyright / The National Archives. Accessed via Ancestry 1911 Census ↩︎

- British Army WWI Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914-1920 Accessed via Ancestry Medal Cards ↩︎

- As noted on the Great War Forum Website https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/244809-gloucestershire-regiment-14th-city-of-bristol-battalion/#comment-2543135 ↩︎

- The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; WWI Service Medal and Award Rolls; Class: WO 329; Piece Number: 1145 Accessed via Ancestry Medal Rolls ↩︎

- As noted on the Great War Forum Website https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/244809-gloucestershire-regiment-14th-city-of-bristol-battalion/#comment-2543135 ↩︎

- The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; First World War and Army of Occupation War Diaries; Class: WO 95; Item: 1 UK, WWI War Diaries (France, Belgium and Germany), 1914-1920 Accessed via Ancestry War Diaries ↩︎

- Death certificate for Elizabeth Keyes, died 3 November 1917 in sub-district Grays, registered in Orsett registration district; certified copy supplied by the General Register Office, Southport, England ↩︎

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2025 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

My great-uncle John Thomas Hopkins, of Coventry, was also killed in this battle, a couple of weeks later on 26 October 1917. He was also a young unmarried working class man of 21, much mourned and missed by his family. He was a Marine, a member of the Royal Naval Division, although he came from the Midlands and had no connections with the Navy or the sea. He has no known grave and is commemorated on Panel 1 at Tyne Cot (the RND Division is listed first on the wall, the RN being ‘the Senior Service’).

I too have visited the area and particularly Varlet Farm, from where the action started on the 26 October. More than 300 Marines were killed that day. However, although he has no known grave, I have learned from WW1 experts on the Great War Forum that “there are a large number of ‘unknown’ Royal Marines interred at Poelkapelle CWGC Cemetery, the number equating closely to the number of Marines killed in action at Varlet Farm, October 1917, 1 mile away”. There are a large number of other ‘unknowns’, too and it is possible, perhaps even likely, that your great-uncle is also interred there. When I visited, I took a boxful of poppy crosses with me and put one on the grave of each unknown marine I could find, I hope his grave was amongst them. I was staying at Varlet Farm (which now operates as a bed and breakfast and has a small museum and an extensive library of books on the period) for both the 90th and 100th anniversaries of his death (along with many other relatives of other men on both occasions). At the centenary a RN Colour party also attended the impromptu but very heartfelt ceremony of remembrance which simply happened in the farmyard, (amongst the relatives who had simply turned up in numbers) presenting a colour flag to the museum.

In a book called ‘Fields of Battle’ by Michael St Maur Shell, published for the centenary of the battle and which is of wonderful photographs of the area now, there is an extract dated 26 October 1917 (the day my great-uncle was killed) from the diary of Leutnant Schafer (Infanterie-Regiment 465) which I find extraordinarily poignant. It reads

“From a small pill-box I have a good view over the battlefield. In front of me is a remarkable sight: a break in the battle to remove dead and wounded. The guns are silent, a deep peace rules over the battlefield. No plough could gouge the fields in such a manner. The chaos is awful to behold. Slowly and carefully, stretcher-bearers with dogs arrive from both sides. Friends and foe alike have their red crosses clearly displayed. Fascinated, I watch this sad task through my field glasses.What a difference: no will to hurt, no raw hatred, just pure humanity.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Many thanks for sharing with me the story of your great-uncle John Thomas Hopkins. Tragically so many young men like John and my great-uncle Harry were taken far too early, their lives were over almost before they had begun. They became a lost generation. I also have three other family members who were lost to the ravages of WW1, two on the western front and also my great-grandfather, who died at Gallipoli. Sadly none of these brave men were ever recovered and are remembered on the burials but have no known grave. My trip this summer was my first to the Western Front and I hope to return and look in more detail at some of the smaller cemeteries and other locations.

I also found that the help of the people from the Great War Forum was invaluable in telling this story. They were able to give me more depth and understanding to the records that I had found. I could not have written this without their help.

Interesting that you mention Poelkapelle cemetery and the possibility that Harry might be buried there. I will certainly put this on my list of places to visit on my return trip. I will have a look at Varlet Farm as well, this sounds like an ideal location to stay and explore in more detail.

Thank you for adding this wonderful and poignant quote from the book called ‘Fields of Battle’ by Michael St Maur Shell. That brought a lump to my throat reading that. That really is a powerful quote. Would you mind if I added the quote into Harry’s story?

LikeLike

Please do, it is very powerful.

LikeLike

I would like to mention yourself as the source, can I mention your name please, and could you let me know what it is please.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly, my name is Glenys Sykes, and thanks for subscribing to my blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am not sure whether a previous comment from me has disappeared into the ether or whether it is awaiting approval but I repeat the text below, just in case. Please delete if this is a duplication.

My great-uncle John Thomas Hopkins, of Coventry, was also killed in this battle, a couple of weeks later on 26 October 1917. He was also a young unmarried working class man of 21, much mourned and missed by his family. He was a Marine, a member of the Royal Naval Division, although he came from the Midlands and had no connections with the Navy or the sea. He has no known grave and is commemorated on Panel 1 at Tyne Cot (the RND Division is listed first on the wall, the RN being ‘the Senior Service’).

I too have visited the area and particularly Varlet Farm, from where the action started on the 26 October. More than 300 Marines were killed that day. However, although he has no known grave, I have learned from WW1 experts on the Great War Forum that “there are a large number of ‘unknown’ Royal Marines interred at Poelkapelle CWGC Cemetery, the number equating closely to the number of Marines killed in action at Varlet Farm, October 1917, 1 mile away”. There are a large number of other ‘unknowns’, too and it is possible, perhaps even likely, that your great-uncle is also interred there. When I visited, I took a boxful of poppy crosses with me and put one on the grave of each unknown marine I could find, I hope his grave was amongst them. I was staying at Varlet Farm (which now operates as a bed and breakfast and has a small museum and an extensive library of books on the period) for both the 90th and 100th anniversaries of his death (along with many other relatives of other men on both occasions). At the centenary a RN Colour party also attended the impromptu but very heartfelt ceremony of remembrance which simply happened in the farmyard, (amongst the relatives who had simply turned up in numbers) presenting a colour flag to the museum.

In a book called ‘Fields of Battle’ by Michael St Maur Shell, published for the centenary of the battle and which is of wonderful photographs of the area now, there is an extract dated 26 October 1917 (the day my great-uncle was killed) from the diary of Leutnant Schafer (Infanterie-Regiment 465) which I find extraordinarily poignant. It reads

“From a small pill-box I have a good view over the battlefield. In front of me is a remarkable sight: a break in the battle to remove dead and wounded. The guns are silent, a deep peace rules over the battlefield. No plough could gouge the fields in such a manner. The chaos is awful to behold. Slowly and carefully, stretcher-bearers with dogs arrive from both sides. Friends and foe alike have their red crosses clearly displayed. Fascinated, I watch this sad task through my field glasses.What a difference: no will to hurt, no raw hatred, just pure humanity.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you are returning to that area of the Battlefields, might I suggest that you pay a visit to the Belgian War Cemetery at Houthulst, not far from Poelcapelle? I visited the British and German cemeteries as many visitors do but our hostess at Varlet Farm suggested we visit Houthult. It was utterly beautiful in autumn, a lovely landscaped layout surrounded by beech trees and with some memorials having photographs added. There are also some graves of Italian prisoners of war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks i will definitely add that to the list, appreciate that.

LikeLike

Such a heartbreaking loss for his family and for so many families whose young men never came home. I’m very impressed by the level of the details you were able to add to this story through research and by visiting this important site in person.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Marian, like all pieces of research this has taken place over a number of years with the final piece of the jigsaw coming when I visited the Western Front this summer

LikeLike

What a moving and beautifully researched tribute to Private Harry Joseph Keyes. Your storytelling brings his life into sharp, painful focus: the young working‐class boy from Grays growing up beside the Thames, stepping into war, and ultimately never returning. The image of the mud, the disrupted lines, the creeping barrage, and the chaos of Poelcapelle are all deeply evocative, and I was especially struck by how you draw out the human cost, not just of Harry’s death, but of his mother’s heartbreak afterwards.

I also appreciate how you place his life in a broader context and show that behind every name on a memorial there was a network of family, hope, and loss. This story reminds us not only to remember, but to try to see the person behind the uniform. Thank you for keeping Harry’s story alive in such a powerful and respectful way.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your kind words Elizabeth that means a lot to me. I had spent a fair amount of time researching Uncle Harry’s life and service over a number of years but this year’s trip to the Western Front enabled me to add some depth and context to his story. It’s so important that the sacrifices made by these brave men and women is forever remembered. I hope in some small way that his voice will now be heard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well written, excellent photos – a terrific read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much I really appreciate that 😊

LikeLike