From the Fields of Herefordshire to the Trenches of France

When I think of the First World War, I don’t just picture the vast battlefields or the rows of white crosses that stretch endlessly into the horizon. For me, it is much more personal. Many of my ancestors fought and died on the battlefields of the First World War, and this is just one of their stories……………

On 26 May 18961, in the small but bustling suburb of Brentford, Middlesex, William Wootton was born, the third of four brothers: Thomas, George, William, and Alfred, children of James and Robina Wootton (née Stone). He was a young child growing up like millions of others across the country, enjoying a simple life, one might even describe it as ‘ordinary’.

I can picture his parents, James and Robina, standing proudly in St. George’s Church in Old Brentford on 18 February 18982, watching as three of their sons, Thomas, George, and William, were baptised together. It must have felt like a moment of pure hope, the kind of day where the future stretched wide open before them.

And like so many families across the country, the Woottons would one day learn that history does not always allow those bright hopes to remain untouched. As I trace William’s story, I often find myself pausing to imagine the everyday moments that never made it into the records. What games did he and his brothers invent in the streets of Brentford? Did he race them along the riverbank, or sneak into the kitchen to steal a piece of bread when no one was looking? Did they play football or cricket in the streets and back alleys, and what mischief did they get up to?

(London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: dro/059/006)

At the time, the family home was located at 2 Layton Cottage, Brentford3. James and Robina had moved to the Brentford area from rural Herefordshire following their marriage in the summer of 18854. James worked as a carpenter, and it is likely, the primary reason for their relocation from the peaceful village of Mansell Gamage was the promise of more consistent employment opportunities in the rapidly expanding suburbs of London. The shift from quiet country life to the bustling outskirts of the capital marked a significant change for the young couple, driven by the economic pull of the vastly expanding capital.

In the 1901 Census5 the family are still residing at 2, Layton Cottage, Old Brentford. William can be found in a typically busy Edwardian household, at home are his parents, James and Robina, with James still being recorded as a carpenter. Also at home are William’s siblings, Millicent, aged 11, Thomas, aged 9, George, aged 6 and Alfred, aged 2.

Old Brentford

Brentford at the turn of the 20th century was a town in transition. While still closely tied to its riverside and industrial roots, the area was experiencing steady growth and modest civic improvements, which included the opening of the fire station in 1898, the public baths in 1896, and the construction of a Carnegie-funded public library in 1904. Layton Cottage stood among other similar homes in the narrow lanes and back streets, forming a close-knit community of working families.

Return to the Countryside

By the 1911 Census6, William’s family had returned to their ancestral home in the rolling countryside of Herefordshire, settling at The Paddocks in Mansell Gamage. The exact reason for their return remains uncertain. Was James struggling to find work in the London suburbs? Did he or his wife, Robina, long for the quiet rural life of Mansell Gamage? Did the pressures of urban life lead James and his wife, Robina, to yearn for the quieter, slower pace of the countryside where they had once lived? While we can’t know for sure the exact reason they moved, sometime between the 1901 and 1911 censuses, James chose to relocate his family back to the familiarity of rural Herefordshire.

At home with William are his parents, James, aged 55, Robina, aged 49, older brother George, aged 16, and younger brother Alfred, aged 12. The rural life there was peaceful, far removed from the mechanised horror that awaited William and his brothers on the Western Front. By the time William grew into adulthood, the world around him had already begun to change. The storm clouds of war were gathering, though I doubt he or his family could have grasped what was to come. For me, it’s heartbreaking to think of how quickly that ordinary life was swept away. By 1914, the fabric of their lives and the world itself would be irrevocably changed. The Wootton household, like many across the Country, was to see four of their young men leave to fight on the shores of Europe for King and Country. Thomas, George, William and Alfred all answered their country’s call to arms, but how many of them would return home?

When each of the boys went off to serve, I wonder what words were exchanged at the door, what promises were made. Did Robina tell them to look after themselves, holding back tears so they wouldn’t see her cry? Did his father stand a little taller with pride as he watched them leave? Their fate uncertain, their return not guaranteed. I will never know for certain, but I can almost hear the echo of those moments.

The Call to Arms

At the start of the Great War, the population of Byford in Herefordshire, including children, was 148, and Mansell Gamage was 116, giving a total of 264 inhabitants7. Fifty-one young men enlisted from the two villages, and thirteen of those, sadly, died. The others returned, but life would never be the same for any of them after the horrors of what they saw. Of those fifty-one men who enlisted, six were connected to the Wootton Family. All six were related, four sons born to James Wootton and Robina Wootton, Thomas, George, William and Alfred and two sons born to John Henry Wootton and Frances Wootton, another Thomas Wootton and another William Wootton, and they were all ‘Cousins’.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, young men like William faced a complex mix of duty, patriotism, and peer pressure. Having seen three of his brothers also answer the call to arms, the outbreak of war stirred a wave of enlistments across Britain, and William could hardly say no, could he? So he joined the Herefordshire Regiment, a local county regiment, where he was assigned service number 4517.

Initially, William underwent rigorous training in Hereford. Soldiers learned to march, handle weapons, and endure long hours of drilling. But these preparations were only the beginning of a brutal education. The reality of modern trench warfare, artillery barrages, and machine guns was vastly different from any drill ground exercise.

Joining the Lonsdales

In September 1916, William was transferred to the 11th Battalion of the Border Regiment8, known as The Lonsdales, receiving a new service number, 27837. The Lonsdales had a fierce reputation, but had suffered devastating losses on July 1st, 1916, the infamous first day of the Battle of the Somme.

That day, the Lonsdales charged into ‘No-Man’s-Land’ near Authuille Wood, only to be cut down by withering German machine-gun fire. They lost 25 officers, including their commanding officer, and 490 other ranks, a catastrophic toll. After such losses, the battalion was withdrawn to regroup and reinforce.

William’s arrival coincided with a battalion in recovery, determined yet haunted by the ghosts of that July morning.

To understand William’s Battalion’s position and how they came to be on the Somme and what would eventually lead to him losing his life, we need to understand a bit more about the British Expeditionary Force in the lead-up to the Somme.

(Photo from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

The Road to the Somme

The origins of the Battle of the Somme arose from a specific set of wartime circumstances. By 1916, Britain’s small professional army of 1914 had been virtually wiped out. Its part-time territorial soldiers had also played a crucial role in halting the advance of the Kaiser’s forces. Now it was the turn of the eager volunteers, men like William Wootton, who had signed up in the early days of the war. Trained and ready, they were prepared to ‘do their bit’.

The decision to fight on the Somme was made for political reasons during the winter of 1915. It was to be a joint offensive where the British and French armies met on the Western Front, coinciding with attacks by Russian and Italian allies on other fronts. The Somme was chosen as the site for this massive summer assault. However, in February 1916, the Germans launched their own major offensive at Verdun, throwing plans into disarray. The French, under immense pressure at Verdun, had to scale back their involvement in the Somme offensive and urged the British to bring forward the attack, an incredibly difficult task given the scale and complexity of the operation.

The strategy was, in essence, simple: a massive artillery bombardment would obliterate the German defences and their troops, clearing the way for an infantry advance and, ultimately, a cavalry breakthrough to restart mobile warfare. But the Germans had spent nearly two years fortifying the Somme. Their defences were deeply entrenched, their front-line villages transformed into strongholds protected from shellfire.

When the whistles blew on the morning of July 1st, 1916, British troops advanced according to a rigid plan. They believed the bombardment had cleared the way. It had not. German troops, sheltered in deep dugouts, emerged quickly once the shelling ceased. Their machine guns and artillery tore into the slow-moving British infantry, encumbered by heavy equipment, who were expecting little resistance.

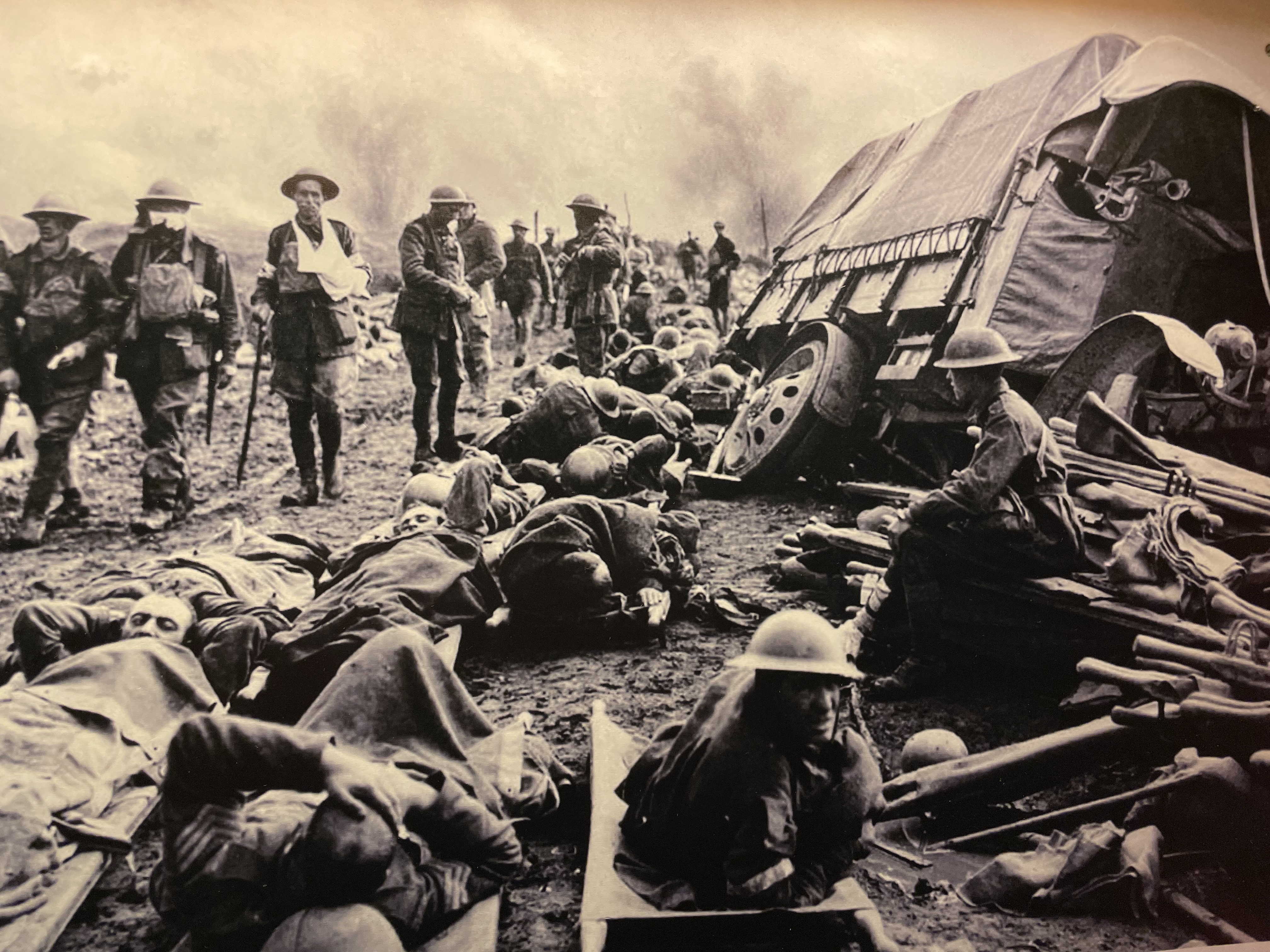

It was a massacre. By nightfall, the much-anticipated ‘Big Push’ had failed. Over 20,000 British soldiers were dead, and 40,000 more were wounded. It remains the darkest day in British Army history.

(The Somme – Photo from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

A new term entered the military dictionary: attrition. The war had become a brutal slog. Conditions in the trenches were hellish. Soldiers faced mud, vermin, disease, and near-constant shelling. Rations were meagre; sleep was scarce. The ever-present threat of death weighed heavily on every man. Letters home often spoke of camaraderie and hope, but beneath the surface was a grim reality few could escape. The Germans fiercely contested every inch of lost ground. Their casualties were as severe as the Allies’, but Britain and its empire could better absorb the losses. By the time the battle ended amid snow and mud in November, British losses had reached 420,000, the French 200,000, and the Germans 600,000. It was a harsh and costly learning curve for the British military9.

The photographs below were taken during my visit to the Sanctuary Wood Trench Museum on the Western Front in July 2025. The preserved trenches and dugouts offer a rare opportunity to step back in time and see the conditions in which soldiers lived, fought, and waited. The narrow passageways, rough timber supports, and scarred earth give a glimpse of the daily reality of trench warfare, where mud, discomfort, and danger were constant companions.

Yet, while these images help us to imagine the physical environment, they cannot fully capture the fear, exhaustion, and unimaginable loss endured by those who served here. The silence of the present landscape stands in stark contrast to the chaos, noise, and horror that once filled these very trenches. Visiting the site is a powerful reminder that behind every trench wall and every stretch of battered ground were countless individual stories of courage, sacrifice, and suffering.

(Photo’s from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

Below is a picture of “No Man’s Land,” as it appeared when I visited the Somme battlefields in July 2025. Today, the fields are peaceful, the air is still, and nature has reclaimed the land. Yet, this calm hides the unimaginable horrors that unfolded here during the First World War.

During the Battle of the Somme in 1916, “No Man’s Land” was the deadly strip of ground between opposing trenches, often just a few hundred yards wide. Soldiers who ventured into it faced relentless machine-gun fire, artillery shells, and the constant threat of death. The landscape was churned into a wasteland of mud, barbed wire, and shattered trees, littered with the remains of men who never made it back.

Standing there, it’s almost impossible to compare the beauty of the countryside today with the scale of the suffering and sacrifice. The silence speaks volumes, a reminder that this peacefulness was bought at a terrible cost.

(No-Man’s Land – Photo from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

The November Offensive: Munich and Frankfort Trenches

By late October 1916, the Lonsdales were sent back to the front near Beaumont Hamel, tasked with taking two heavily defended German positions: Munich and Frankfort trenches on Redan Ridge.

On November 18th, under the cover of a bitter sleet and snowstorm, the Lonsdales launched their assault. The freezing weather was merciless, and the ground became a treacherous quagmire, sucking boots and equipment into the mud.

British artillery was supposed to soften German defenses before the infantry attack. But the barrage fell short, inflicting terrible casualties on the advancing British soldiers instead. German machine guns, relatively unscathed, unleashed a deadly hail of bullets.

Despite this, small groups of soldiers managed to reach Frankfort trench, where the battle devolved into savage close-quarters combat. Men fought with bayonets, rifle butts, and even their bare hands in the freezing mud. The air was thick with smoke, the cries of the wounded, and the deafening roar of gunfire.

(Map of the village of Beaumont Hamel taken on my visit in July 2025)

William’s Final Hours

William Wootton was among those who advanced that day, November 18th, for the final assault on Redan Ridge.. His precise fate is unknown; his body was never recovered from the shattered battlefield. Like so many others, he was swallowed by the chaos and carnage of the fight.

As darkness fell, only a few survivors managed to return to British lines. Many wounded men were left stranded, hiding in shell craters or the shattered landscape, enduring the freezing cold and agonizing injuries through the night. Rescue was often impossible amid continued fighting and nightfall.

William’s parents would not receive definitive confirmation of his death for many months. The uncertainty, the waiting, and the fear were shared by countless families across Britain.

Herefordshire’s Heavy Toll

The loss of William was part of a much larger sacrifice. Ninety-two men from the Herefordshire Regiment who had transferred to the 11th Border Regiment were killed or died of wounds on the Somme during the week of November 18th–25th, 191610.

The impact on Herefordshire was profound. Small villages and tight-knit communities lost sons, brothers, and friends. The war’s reach was felt in every corner of the county, in every churchyard, and in every household that mourned.

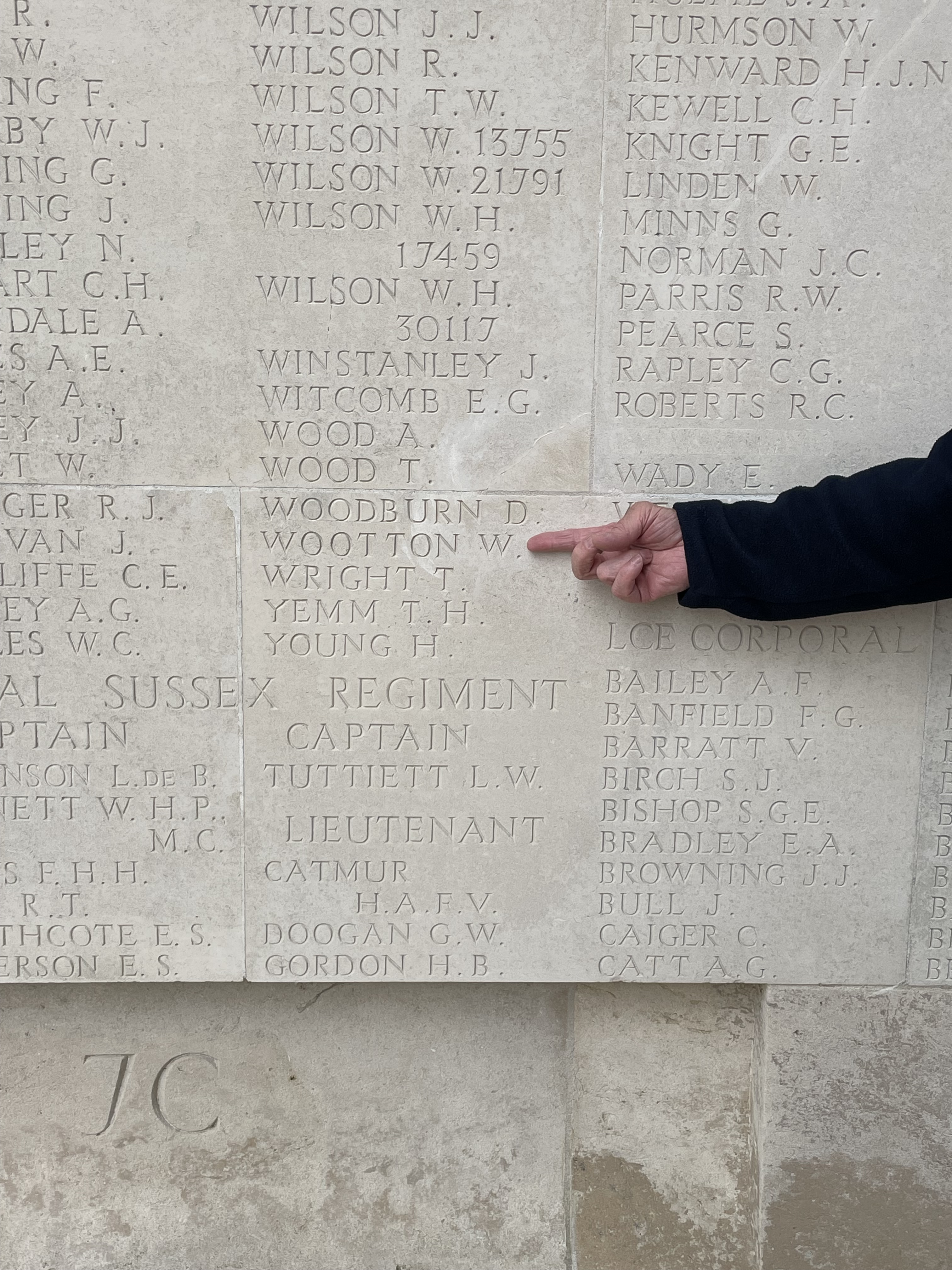

Remembering the Missing

William Wootton’s name is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, which is dedicated to over 72,000 British and South African soldiers who died on the Somme fighting, but have no known grave. In July 2025, I visited the battlefields of the Western Front and was able to pay my respects to William Wootton and all of the brave men who tragically lost their lives on the Somme.

(Pictures from my collection, taken during my visit to the Thiepval Memorial in July 2025)

There is also a framed memorial to all the brave young men of the Villages of Byford and Mansell Gamage who served King and Country during WW1, including the names of those that sadly made the ultimate sacrifice. With special thanks to Sue Hubbard, Churchwarden at Byford Church, Herefordshire, for sharing the picture of the memorial that hangs in Byford Church.

(Image courtesy of Sue Hubbard)

Legacy and Reflection

William’s story is one of courage, loss, and the enduring spirit of a generation caught in the machinery of war. He was a young man who left behind the familiar fields of Herefordshire to face unimaginable horrors, fighting not just for victory but for survival and for the future of a world torn apart. Today, as we remember William and the countless others lost on the Somme, we honour their bravery and the terrible cost of war. Through stories like his, the echoes of the past remind us of the preciousness of peace and the resilience of the human spirit.

Sources

- Birth record for William Wootton taken from London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms 1813-1924 from the parish of Saint George, Old Brentford, Hounslow 1883-1902 Accessed via Ancestry Baptism Record for William Wootton ↩︎

- Baptism record for William Wootton taken from London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms 1813-1924 from the parish of Saint George, Old Brentford, Hounslow 1883-1902 Accessed via Ancestry Baptism Record for William Wootton ↩︎

- Address taken from the Baptism record for William Wootton taken from London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms 1813-1924 from the parish of Saint George, Old Brentford, Hounslow 1883-1902 Accessed via Ancestry Baptism Record for William Wootton ↩︎

- Marriage Record FreeBMD September Quarter 1885 Islington District volume 1b page 642 ↩︎

- 1901 England and Wales Census Class: Class: RG13; Piece: 1194; Folio: 41; Page: 12 ©Crown Copyright / The National Archives. Accessed via Ancestry 1901 Census ↩︎

- 1911 England and Wales Census Class: Class: RG14; Piece: 15756; Schedule Number: 52 ©Crown Copyright / The National Archives. Accessed via Ancestry 1911 Census ↩︎

- Information recieved from Sue Hubbard, Churchwarden at Byford Church, Herefordshire. ↩︎

- Information taken from the Herefordshire Regiment Museum Website https://herefordshirelightinfantrymuseum.com/uploads/redan-ridge.pdf ↩︎

- The vast majority of the information regarding the Battle of the Somme came from my visit there in 2025. ↩︎

- Information taken from the Herefordshire Regiment Museum Website https://herefordshirelightinfantrymuseum.com/uploads/redan-ridge.pdf ↩︎

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2025 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

When touring round France we often come across war memorials and reading the names we can’t begin to imagine the horror suffered by families losing husbands, sons, cousins, nephews. Your narrative paints a vivid and devastating picture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was very special to pay my respects to my ancestor Sheree

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can imagine

LikeLiked by 1 person

How emotional to see the places where your ancestor and his cousins fought so bravely and too many soldiers lost their lives. Thank you for sharing something of their background, the towns where they grew up, and your photos of memorials to their sacrifices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Marian it’s so important that their sacrifice is never forgotten

LikeLike

You’ve written a wonderful tribute to the Wooten family and remembrance for their sufferings and sacrifices. No one should have to go through these horrors. The preciousness of peace needs to become more apparent at the highest levels of governments around the world. An end to the madness of war needs to happen sooner than later.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Eilene it’s our job to remember the sacrifice they gave and ensure that their memory lived on

LikeLiked by 1 person