From Orchard Fields to Flanders Fields: The Story of Thomas Wootton

Thomas Wootton was born on March 26th, 18921, in the village of Byford, Herefordshire, the sixth oldest of eight children born to John and Frances Wootton. Raised on the family farm at Lower House, he attended Byford School from 1898 to 1906. A quiet rural upbringing shaped his early life, where he was surrounded by a close-knit community where life revolved around the seasons, the land, and the church.

Aged 9, we find Thomas in the 19012 census living at the family home in the small village of Byford in Herefordshire, along with his parents, John Henry Wootton and Frances Emma Wootton. Also living at home were Thomas’ siblings, Frances Mary, aged 16, Helen, aged 13, Annie, aged 10, William, aged 7 and Jessie, aged 3. It’s also worth noting that at the time, the Wootton family were doing well enough to employ a young servant named John Herbert. Thomas’ father, John Henry Wootton, ran a substantial farm at the time and also owned a large Orchard. Pictures of the Wootton family home and farm at Byford can be seen below.

In 19113, once again, we find Thomas at work, working on the family farm, where he is recorded on the census as a farmer’s son working on the farm. His father, John Henry Wootton, is still running the family business of the farm, and those old enough to work on the farm are helping run the family business. The family also had living with them a servant by the name of James Rogers, who was basically a live-in farm worker.

As the eldest surviving male, one might have expected Thomas to eventually take over the running of the family farm and business, but for whatever reason, that did not happen. Thomas wanted to see the world. In 1913, looking for new opportunities beyond the English countryside, Thomas emigrated to Australia, sailing aboard the SS Demosthenes from London to Fremantle. He was among tens of thousands who left Britain in the early 20th century, drawn by Australia’s promise of land, work, and adventure. Settling in Western Australia, he took up work as a dairyman in the small town of Helena Vale, just east of Perth.

(Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk)

Dreams of a New World

When Thomas left rural Herefordshire in 1913 to begin a new life in Australia, he was part of a broader story of migration that shaped the early 20th century. His decision was not unusual for a young man from the English countryside. Across Britain, thousands of men and women were lured overseas by a mix of hope, necessity, and adventure.

For a small farmer in Herefordshire, the prospects at home were limited. Britain was crowded, and opportunities to own land were scarce. In contrast, Australia promoted itself as a country of open fields and boundless opportunity. Land was cheap and, in some cases, even granted to settlers willing to work it. For young men like Thomas, the promise of establishing a farm or finding steady employment in agriculture offered the chance of independence, something hard to achieve in the class-bound English countryside.

The economic pull was strong. Industrial Britain was plagued by cycles of unemployment, strikes, and poverty. Wages were low, especially in rural areas, while Australia’s expanding economy offered better pay for manual labour. The new nation was still building its railways, sheep stations, and cities, and it needed workers. A healthy young man could expect not only employment but the possibility of rising through his own hard work in ways that seemed less attainable back home.

Migration was not only a personal choice but also encouraged by government policy. Both Britain and Australia supported assisted migration schemes, sometimes even subsidising or covering the cost of passage. Emigration was framed as both practical and patriotic: young Britons were told they could strengthen the bonds of Empire while helping to “populate or perish” in Australia. Posters painted glowing images of sunlit farms and endless opportunity, contrasting sharply with the smoky factories and crowded towns of England.

Beyond economics and politics, there was the lure of adventure. For many, Australia was imagined as a land of freedom and fresh beginnings, a place far from the rigid hierarchies of Britain. Even if reality often fell short of the romantic image, the idea of sailing across the world to start anew carried an irresistible sense of possibility.

Of course, there were push factors as well. In 1913, Britain faced social unrest, labour strikes, and uncertainty. For some young men, emigration may even have felt like a way to escape Europe’s rising tensions and the shadow of looming war. Ironically, Thomas would return just a year later, drawn back by duty to fight in the First World War.

His journey, first outward, then back, reflects both the optimism of migration and the harsh pull of history. Like many of his generation, Thomas sought opportunity on distant shores, only to be called home to a conflict that would reshape the world.

Answering The Call of Duty

Thomas’ dreams of a fresh start and a better future were cut dramatically short. In August 1914, war broke out in Europe. Barely a month later, on 16 October 1914, Thomas enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force at Blackboy Hill Camp4. He became part of the 16th Battalion, 4th Brigade, under the leadership of Colonel John Monash, a name that would become legendary in Australian military history. At the time, he was 22 years and 6 months old.

(Thomas Wootton Australian Infantry – Photograph from Anne Teesdale)

Gallipoli: A Baptism by Fire

Thomas and the men of the 4th Brigade embarked for Gallipoli on Boxing Day, 1914. On 25 April 1915, they landed at Anzac Cove, joining the brutal Gallipoli campaign. Conditions were hellish: A brutal terrain, relentless enemy fire, extreme heat in the summer, followed by freezing cold winters, plus the ever-present threat of disease. After months of hardship, the Allies evacuated the peninsula in December 1915. Thomas was among the sick and was evacuated with jaundice to Alexandria, Egypt5.

His service continued in France the following year, where the AIF became part of the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. In December 1916, during the bloodbath of the Battle of the Somme, Thomas sustained a gunshot wound to his left thigh and buttock6. He was evacuated to England, where he developed gas gangrene, a deadly bacterial infection often fatal in the trenches. But miraculously, thanks to the wonders of the medical staff and his own resilience, he recovered again to return to active duty.

(Australian National Archives)

Love in the Shadow of War

While recovering in England, Thomas met and married Mary Louisa Staples, a Scottish woman from Dalkeith, on 30 April 1917 in Newmarket, Cambridgeshire7. Though the exact circumstances of their meeting are uncertain, family testimony suggests that Mary had attended the wedding of Thomas’s sister, Frances, in Edinburgh the year before, and they met there. Although they didn’t know it at the time, like many couples of this time, their union was all too brief, a moment of joy amongst all the chaos and death.

(Wedding of Thomas Wootton and Mary Staples – Photograph from Ann Teesdale)

The Ypres Salient and the Battle of Polygon Wood

Not content with already serving in two of the largest battles of the `Great War, Thomas had one more huge battle ahead of him. In August 1917, Thomas rejoined the 16th Battalion in Belgium, where he was promoted to Sergeant8. The battalion was stationed in the Ypres Salient, preparing for what would become one of the most costly and strategic battles of the war: The Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele)9. The picture below shows “Hellfire Corner,” once described as the most dangerous place on earth. During World War I, it became infamous for the relentless German shellfire that pounded the exposed position. Situated along the Menin Road at Ypres, it was a place Thomas and his battalion would soon come to know all too well.

(Photo from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

This campaign aimed to break through German lines and seize control of vital ridgelines near Ypres. The Australian 4th and 5th Divisions were tasked with advancing across a heavily fortified and scarred landscape, with German pillboxes and barbed wire defences spread across the shattered forest once known as Polygon Wood10.

(Photo from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

At 5:50 am on 26 September 191711, the attack on Polygon Wood commenced behind a meticulously timed artillery barrage. Thomas’s battalion advanced on the northern flank, near Zonnebeke, supporting the main thrust toward the Butte, a large German strongpoint in the heart of the wood. However, miscommunication proved deadly. Some elements of the line advanced too early, moving into their own artillery fire. Sniper activity was intense. Despite these setbacks, the Australians succeeded in taking their objectives. But the cost was heavy: the 16th Battalion alone suffered over 100 casualties. Tragically, during this advance, Thomas Wootton lost his life. He was 26 years old. Like those of the tens of thousands of men who died on the Western Front, his body was never recovered, and like so many of his generation, he has no known grave.

A Soldier’s Legacy

In Britain, soldiers were encouraged to write “short-form” wills before heading to the front. Many used a page in their pay book (known as a “Soldier’s Will”), where they could jot down who should receive their effects if they died. In the notes that Thomas had prepared, he left £20 to his sweetheart, Mary Staples, and the remainder of his estate to his mother in Byford.

(Australian National Archives)

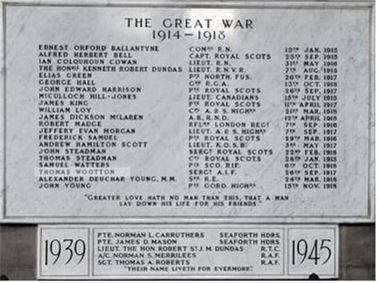

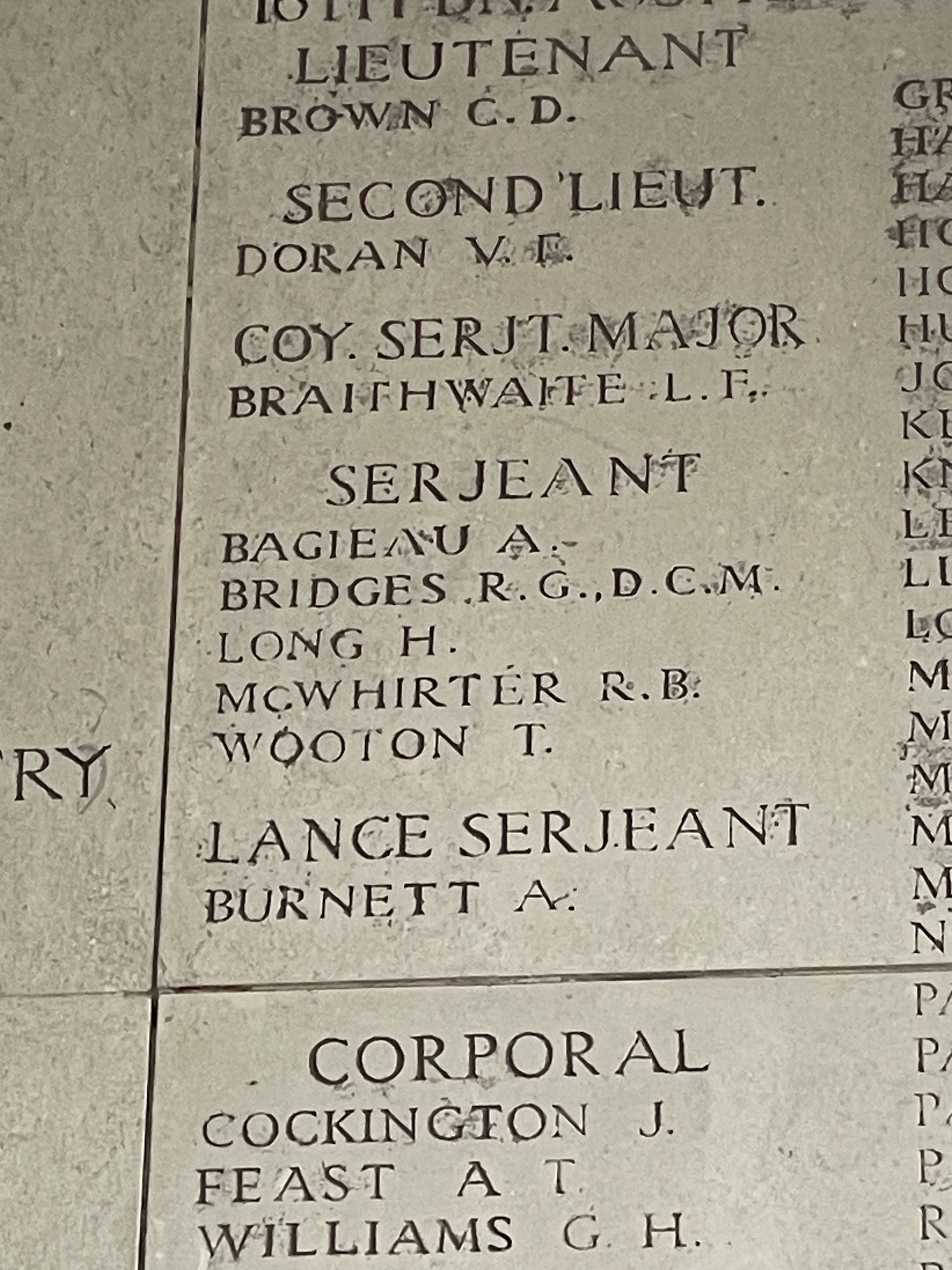

Thomas’s courage and bravery live on in the form of three memorials in three different countries that bear his name:

- Menin Gate, Ypres, Belgium

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra

- St Mary’s Episcopal Church, Dalkeith, Scotland, (Mary’s hometown)

(St Mary’s Episcopal Church, Dalkeith – Image courtesy of Beth Page, South Australia)

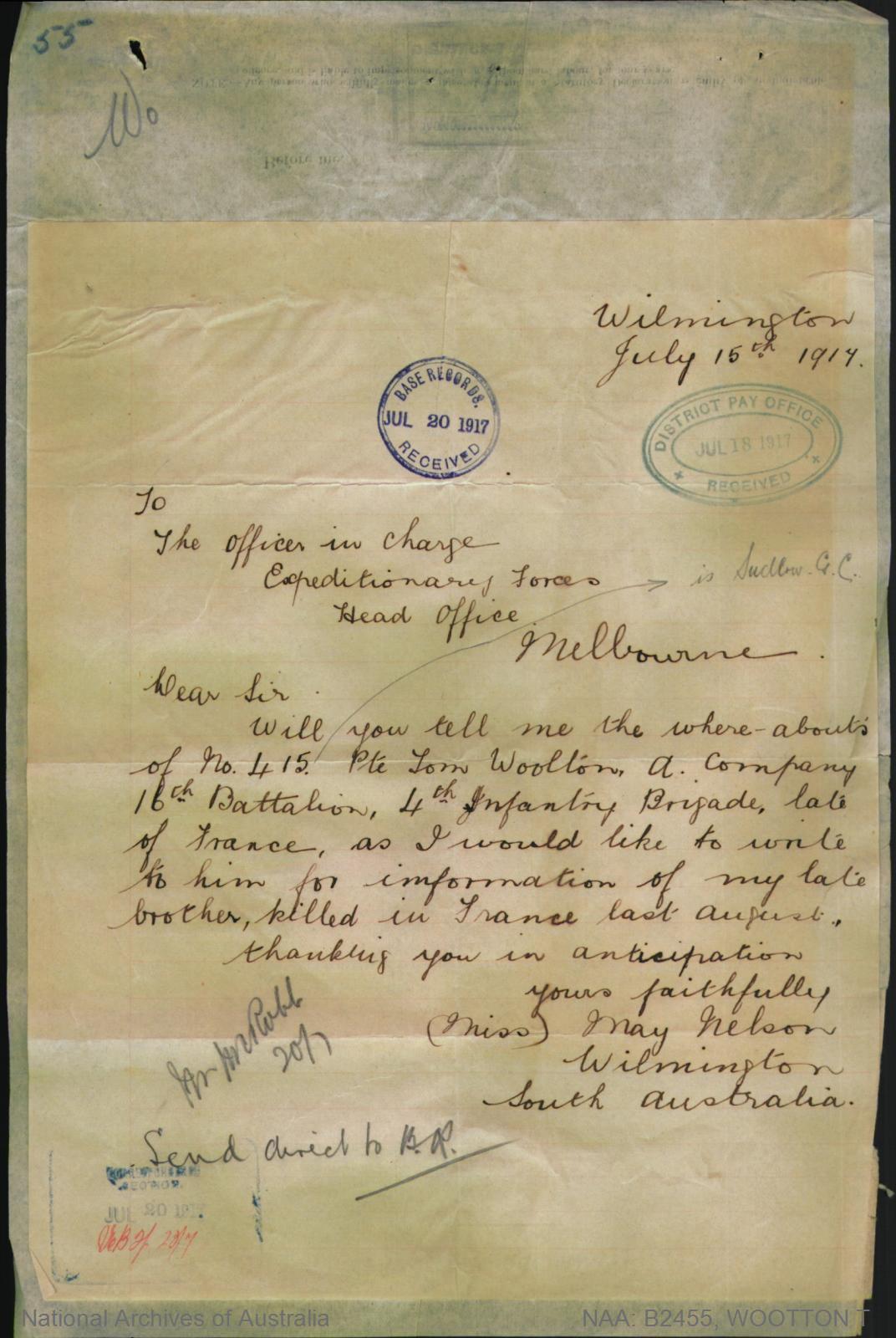

In official war records, we can trace his journey through hospitals, battlegrounds, and training camps. Included are personal documents: medical charts, promotion notices, and a remarkable letter from a woman in South Australia named Miss May Nelson, seeking news of her brother, who had died the year before. She believed Thomas might have known him. These letters, full of quiet desperation, are a haunting reminder of the rippling grief of war. Over forty-five documents helped me to piece together the story of what Thomas lived through during the war.

(Australian National Archives)

The Cost of War

To understand Thomas Wootton’s sacrifice, we must also understand the world he came from. At the turn of the 20th century, rural life in England and Australia was demanding and often austere. Education ended early for many; children worked on farms or in local trades. Emigrants like Thomas sought new beginnings abroad, lured by Australia’s land grants and promises of prosperity. The First World War shattered those dreams for millions. Modern warfare introduced tanks, poison gas, and machine guns, rendering old tactics obsolete. The mud of the Western Front was so deep that men and horses drowned in shell craters. Disease, lice, and constant fear shaped everyday existence. Yet amid it all, men like Thomas continued to serve, often returning to the line even after serious wounds. In many ways, Thomas Wootton’s story is not unique, but it is deeply personal. It’s the story of ambition, bravery, resilience, and love in the face of overwhelming odds.

Lest We Forget

In the summer of 2025, I visited the Western Front and witnessed the enormity of the sacrifice and loss endured by so many brave men and women, including Thomas Wootton. It is our duty to ensure that their sacrifice and legacy live on, and that future generations continue to remember them. Thomas Wootton is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial, alongside more than 54,000 others who gave the ultimate sacrifice.

(Photos from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

Sergeant Thomas Wootton’s story is one of courage, hope, sacrifice and enduring remembrance. He left home with hope for a better life, for a future. Instead, he became part of one of history’s greatest tragedies. His name lives on, not only carved in stone, but in family memory and in the shared story of a generation lost to war. His courage, like that of so many, reminds us of the fragility of peace and the enduring cost of conflict.

A soldier dies twice: once in battle, and once when he is forgotten.

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2025 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

- England, birth certificate (certified copy) for Thomas Wootton, born 26 Mar 1892; registered June quarter 1892, Wembley, Herefordshire, Registration District reference 6A/516 ↩︎

- 1901 England and Wales Census Class: Class: RG13; Piece: 2486; Folio: 77; Page: 1 ©Crown Copyright / The National Archives. Accessed via Ancestry 1901 Census ↩︎

- 1911 England and Wales Census Class: Class: RG14; Piece: 15756; Schedule Number 36 ©Crown Copyright / The National Archives. Accessed via Ancestry ↩︎

- Australia, World War I Service Records, 1914-1920 National Archives of Australia; Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920 via Ancestry Service Records ↩︎

- Australia, World War I Service Records, 1914-1920 National Archives of Australia; Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920 via Ancestry Service Records ↩︎

- Australia, World War I Service Records, 1914-1920 National Archives of Australia; Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920 via Ancestry Service Records ↩︎

- Marriage certificate for Thomas Wootton and Mary Louisa Staples, married 30 April 1917, Newmarket, Cambridgeshire, registration district, Essex; certified copy of entry in the marriage register, supplied by the General Register Office, Southport, England ↩︎

- Australia, World War I Service Records, 1914-1920 National Archives of Australia; Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920 via Ancestry Service Records ↩︎

- History of the Third Battle of Ypres website which can be found Here ↩︎

- The Battle of Polygon Wood link Here ↩︎

- Information taken from the Anzac Memorial Website link Here ↩︎

It’s amazing how much you’ve uncovered about your family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sheree it’s a lifetimes work really

LikeLiked by 1 person

A beautifully recorded story, well-researched and made a lovely read. Thank you for sharing Thomas’ life history.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for reading Thomas’ story his legacy and sacrifice will always be remembered now

LikeLike

A sad story, and sadly familiar story for young men of that time, beautifully told. Visits to the Battlefields really do add so much to our understanding of the scale of the sacrifice they made for us.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your kind words that means a lot. It’s our job to keep remembering and telling their stories so that their sacrifice is never forgotten

LikeLike

Thank you, part of Thomas’s story is that of my grandfather – who migrated from London to NZ with his parents when he was a child, in the 1880’s. He enlisted in March 2017 and was part of A Company 28th Reinforcements, 1st Battalion Auckland Regiment. After training in England he was in Etaples, and took part in the Third Battle of Ypres, and was only in the field for 2 weeks before being badly wounded. Unlike Thomas, he did survive, although he suffered for the rest of his life with the after effects of being gassed. Your photographs illustrate the hell these men endured. You are quite right – we must keep telling their stories, in the hope that they don’t die a second time. I am now the last person alive who remembers my grandfather.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for sharing with me the similar journey that your grandfather had. Thankfully he survived the war albeit carrying the scars from the battlefield. It’s our job to pass the baton over to the next generation to ensure that their memories live on.

LikeLike

What a compelling journey, with wonderful photos and records.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Joy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thomas would have been proud to have his life and legacy preserved by you in this moving and well-researched post. His name will be remembered for many years to come.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Marian his memory and story will live on

LikeLike

Beyond tragic – surviving Gallipoli, only to die at Passchendaele. His poor mother – losing him twice – first to Australia and then to a senseless war. And his wife – I so feel for her. While she must have known the possible outcome, I can only imagine the depth of her grief upon learning of Thomas’s death. Her story mirrors that of the wife of my Great-Uncle Alfred.

I have Alfred’s will – it is headed Informal Will – a basic form recording his details and then a brief handwritten missive, leaving everything to his wife in the event of his death. He signed it on July 4, 1915.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Teresa, it’s such a tragic loss of life so so many families suffered. I am assuming great Uncle Alfred also never returned?

LikeLiked by 2 people

No, he was wounded in November 1915 and died the following November at a hospital in Sunderland. He’d been there about a year – his DC state CoD as “Compound comminuted fracture of the pelvis and femur, and perforation of bladder; wounds received in action in France. Asthenia.” I hope my great-grandmother and his wife were able to travel north from London to visit him before he died.

LikeLike