During a visit to the Western Front in the summer of 2025, I was told a story that has stayed with me ever since. It was not a story of sweeping offensives or celebrated generals, nor one that fits comfortably into the familiar narratives of the First World War. Instead, it was a small, human story, the kind that exists on the margins of history and is easily overlooked. At its centre are a German soldier, a fragment of stained glass, and the long after-effects of a war whose consequences did not end when the guns fell silent.

The story is rooted in Beaumont-Hamel, a place whose name is inseparable from the Somme and the immense losses suffered there, particularly by British and Newfoundland regiments. That association has come to define how the place is remembered. Yet Beaumont-Hamel, like so many villages along the Western Front, was not always a battlefield or a memorial landscape. In 1914, during the opening months of the war, it was a small French village, and at its centre stood the village church.

As the Western Front took shape in the late summer and autumn of 1914, Beaumont-Hamel found itself drawn into the conflict. By October of that year, German forces had occupied the village, and the front soon solidified into the entrenched lines that would scar the landscape for the next four years. Exactly how the village changed hands is not recorded in detail in wider operational histories, but regimental traditions and later accounts suggest that the occupation followed fighting in and around the village during this early phase of the war.

Some regimental histories associate the occupation of Beaumont-Hamel with Reserve Infantry Regiment 99, describing a dawn advance into the village in early October 1914. These accounts are vivid and consistent, but they are not fully corroborated by broader historical sources, which tend to note the German occupation of the area without recording a precise date. What can be said with confidence is that by October 1914, the village, including its church, lay behind German lines.

During this period of fighting and bombardment, the village church was badly damaged. Shells and bullets tore through the building, smashing stonework and shattering its stained-glass windows. The ruins of the church, like much of Beaumont-Hamel itself, were subsequently incorporated into the German defensive position and would remain so until November 1916.

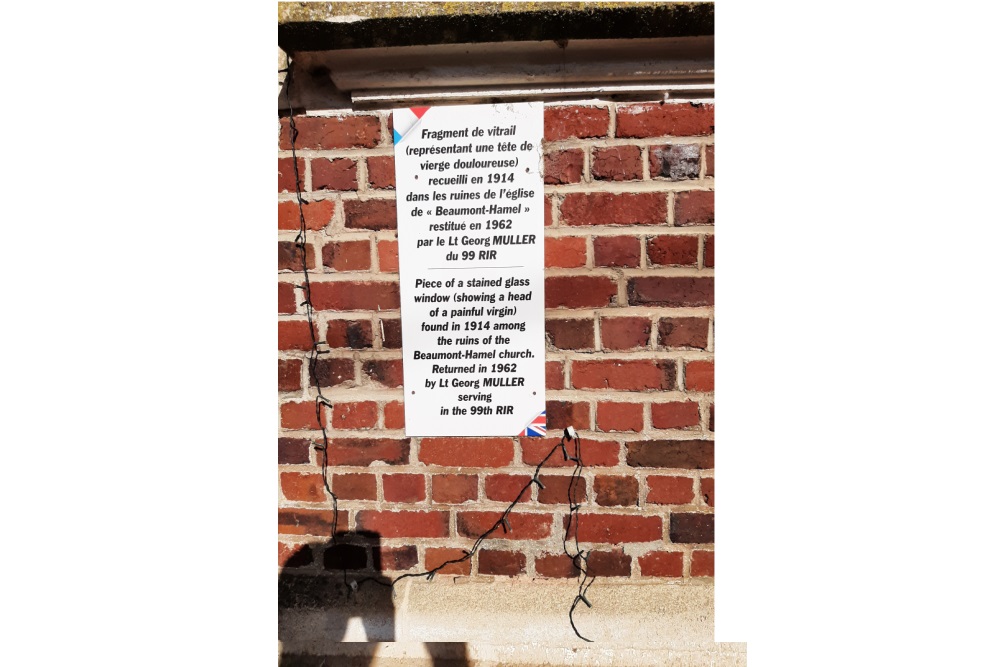

It was among these ruins, sometime during this early phase of the war, that a German officer found a small fragment of stained glass lying in the debris. The piece depicted the head of the Madonna, a simple image, once part of a larger window. The officer was Leutnant Georg Müller (or Mueller), and while some details of his identity remain uncertain, the broad outline of the story is remarkably consistent across local histories and guidebooks.

According to the well-known Holts’ Guide to the Somme, Müller was serving with Infantry Regiment 99. This may be a small but understandable error. Other sources point instead to Reserve Infantry Regiment 99 as the unit most closely associated with Beaumont-Hamel during this period. In the published regimental history of that unit, a Reserve Leutnant G. Müller is mentioned as leading a platoon during early fighting in the area. There is no conclusive proof that this officer was the same man who later recovered the stained glass, but the coincidence is striking. It is entirely possible, perhaps even probable, that the man who picked up the fragment from the rubble was also one of those who had entered the village under arms.

What is beyond doubt is what Müller did next. Rather than discarding the fragment, he kept it. He carried the small piece of stained glass with him for the remainder of the war. Whether he regarded it as a religious object, a reminder of home, or simply a lucky charm, we cannot know for certain. Perhaps it was all of these things at once. In a war defined by destruction on an industrial scale, the survival of such a fragile object and the decision to preserve it, feels quietly significant.

The war dragged on. Beaumont-Hamel became a name etched into history in July 1916, when British forces attacked across ground that had already been fought over for nearly two years. The village itself was eventually taken by Allied troops in November 1916, and what remained of it was little more than ruins. Like so many communities in northern France, Beaumont-Hamel had to be rebuilt almost from nothing after the war.

Decades passed. Then, in 1962, long after the guns had fallen silent and the battlefields had become places of remembrance, Georg Müller returned to Beaumont-Hamel. By then, the church had been rebuilt. Müller, or possibly members of his family acting on his behalf, brought back the fragment of stained glass that had travelled with him through the war, and it was returned to the church from which it had come.

Today, the original fragment is incorporated into a memorial window in the church. It is no longer merely a relic of destruction, but part of a deliberate act of remembrance and reconciliation. A piece of glass broken by war, carried by a former enemy, and finally restored to its place decades later, it’s hard to imagine a more fitting symbol of the long, complicated aftermath of the First World War.

Stories like this matter because they remind us that history is not only made up of dates and casualty figures, but of individual choices. Müller’s decision to pick up that fragment in 1914, to keep it safe, and to return it nearly fifty years later, connects destruction with restoration, and war with peace. Standing in Beaumont-Hamel in 2025, hearing this story, I was struck by how such small acts can resonate across generations.

For those of us who walk the old battlefields today, often tracing family connections to the men who fought there, these quieter stories provide a different perspective. They do not diminish the suffering or the loss, but they add another layer, one that speaks of shared humanity, even in the darkest of times.

The photographs below of the church and its stained-glass window were taken by Koos Winkelman for the https://www.tracesofwar.com/ website and are shared here with his kind permission.

My good friend Kym Lucas has also shared a blog she wrote that has a strong connection to this story, and one I felt was worth sharing with you all.

In Kym’s own words:

I hope that, in viewing these works, you are reminded, as I was, that it is possible to create beauty even in the midst of destruction, a concept I find especially important to keep in mind right now.

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2026 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

Bringing the stained glass fragment back to the church was a show of faith and a way of healing for himself and for all those who went to war or were caught up in it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s a remarkable story and just goes to show that sometimes the most incredible stories can be found in the most unlikely of places

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing this beautiful account. It helps remind us we are human, even within the horrible inhumanity of war. To imagine a soldier carrying a shard of glass through his whole war … well, it’s incredible, really.

It makes me wonder, did he take it out and look at it, searching for a shred of hope that the war would end? That someday life would return to a new normal? I can’t imagine, but his actions give me hope that we also will get through this bad time of people’s inhumanity to others, though I’m too old and cynical to believe we will ever have a lasting peace, certainly not worldwide anyway.

Why do we do it, do you think? Why are there always men (and I’m sorry, but it is almost always men) who think that no matter what we/they have, we/they require more even when there are others in the world with so much less?

Rhetorical question. I don’t expect an answer.

However, I think you’d be interested in a traveling exhibition called “Remembered Light,” which I was fortunate enough to visit last year(https://rememberedlight.org/). It shares the theme of rebuilding from destruction. (Here’s my post about it: https://thebyrdandthebees.wordpress.com/2025/01/27/remembered-light/.)

When my daughter and I walked into the exhibit, we were greeted by the Coventry Cathedral, a building familiar to us both. My husband grew up in a village on the outskirts of Coventry, and we usually walk through the ruins when we visit family nearby. It is always a moving experience.

I don’t know how often the Remembered Light exhibit tours, but I do know there is a hope/plan of building a permanent place for its display. I think you’ll like reading about if you choose to do so. And I promise I’m not just looking for more hits on my blog. I write that for myself and look upon it as shouting into the void. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Kym, thank you so much for your thoughtful comments and for taking the time to read this remarkable story. Part of me likes to think that, in his darkest moments, the shard of glass represented hope — hope that he would survive the war, and hope that he would one day return to his homeland and to the people he loved.

Thank you also for sharing the details of the Remembered Light Project. These pieces are absolutely incredible — stunning windows and fragments of glass, each carrying its own unique story. Thank you so much for sharing them with us. If I may, I would love to add a link to your wonderful blog at the end of my post, as the two stories feel deeply connected.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d be delighted and honored for you to link to my blog because I also was struck by the similarity of the stories. And, also like you, I think both of these men held on to these shards in hope that someday the war would and the world be rebuilt. Lately, I cling to the fact that the world has survived horrible times and found a way through. I find the study of genealogy and history offers a glimmer of hope to those of us in the present.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will add the link now Kym. I think you’re right, if we look back through history there have been some awful dark times, but mankind always finds a way to get through in the end. We have to believe that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m clinging to that hope.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a wonderful story. It was a miracle he survived the war to return the stained glass.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for comm enting and reading this incredible story.

LikeLike

such a lovely story Paul. The write ups of your visit in the summer inspires me to one day make that trip.

Best regards Christine

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Christine, i am glad you have enjoyed my stories from my visit to the western front and hopefully one day you will also get the chance to visit.

LikeLike

This is a very touching story, Paul. As you say, it is a footnote to a larger history. But those footnotes really ARE the story, to me. It’s in the personal that we truly come to understand the impersonality of war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true Eilene and an excellent quote!

LikeLiked by 1 person