Private William Richards Crump was born in Birmingham in 1893, the youngest of two boys born to Minnie Crump. His baptism, alongside that of his older brother Francis, took place on 11 August 1894 at St James Church, Wandsworth. The brothers shared the unusual middle name Richards, which was almost certainly a quiet clue to the identity of their biological father, whose name was never recorded.

Minnie’s life was far from easy. She married Albert Shipley in 1895, only to be widowed seven years later, before marrying Frederick William Eacock, with whom she raised a large blended family. William grew up surrounded by many step-siblings in the busy streets of Handsworth, Birmingham.

William’s childhood in Handsworth unfolded in a small terraced house crowded with siblings and step-siblings. His days would have started with the routine of school, and the afternoons would most likely have been filled with errands, chores, like most young boys his age. The streets were his playground, narrow, sooty lanes where boys chalked hopscotch grids on the pavement, swapped marbles, and played make-believe battles long before the real war reached anyone’s doorstep.

On 1 February 1914, just months before Europe descended into the turmoil of the First World War, William married Ann Jane Worrall at the Parish Church of Immanuel in Birmingham. At the time, he was working as a carter, earning a modest living through skilled, physical labour. On the marriage record, William named his stepfather, Frederick Eacock, as his father, a touching acknowledgement of the man who had clearly become a true father figure in his life.

Their first son, William Henry Crump, was born only a few weeks later, on 6 March 1914, bringing new joy to the young couple as the world around them grew increasingly uncertain. A second boy would follow at the end of 1917. But tragically, William would never have the chance to meet his second-born child. By then, he had been swept into the horrors of war, and fate, along with the advancing German Army, had other, heartbreaking plans for him and his family.

Enlistment and the Journey to War

With the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, William was quick to enlist. Although his personal service records were destroyed during the Second World War, his surviving regimental numbers allow us to trace the outline of his military path.

He enlisted with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment around 5–9 September 1914, receiving the number 6179. Just weeks later, around 21–22 September 1914, he was transferred to the 11th (Service) Battalion, Hampshire Regiment, a unit that would soon become the Pioneer Battalion of the 16th (Irish) Division. When William Richards Crump first arrived in France in December 1915, he entered the war as a Pioneer soldier, a role that has often been overlooked but was absolutely essential to the functioning of an army at war. Pioneer battalions worked at the front, under fire, building the infrastructure that made combat operations possible: trenches, dugouts, wiring, communication lines, roads, mule tracks, water points, and strongpoints. In the worst periods, such men worked by day and dug by night, often closer to the enemy than the infantry themselves.

William arrived in France on 18–19 December 1915, his first Christmas spent in the mud and cold of the Western Front. From that point on, William’s war would take him through some of the worst of the conflict: the Battle of the Somme in 1916, followed by the battles of Guillemont and Ginchy and finally, the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917, known to history simply as “Passchendaele.”

The 11th Hampshire Regiment In November 1917

After their heavy involvement in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) during the summer and early autumn of 1917, the 16th (Irish) Division was withdrawn from the mud-soaked Ypres area around September/early October. The division, still exhausted, understrength, and recovering from the massive losses of the summer, was moved south to the Béthune–La Bassée sector, north of Lens, as part of a quiet “rest sector” on the Western Front.

However, “quiet” on the Western Front rarely meant safe. This area was notorious for persistent enemy shelling, especially from high-velocity German guns firing on known work sites. There was also the threat of the constant harassing fire from trench mortars and sniper positions. Plus, of course, the relentless fatigue of working in dangerous and exhausting labour conditions for Pioneer units.

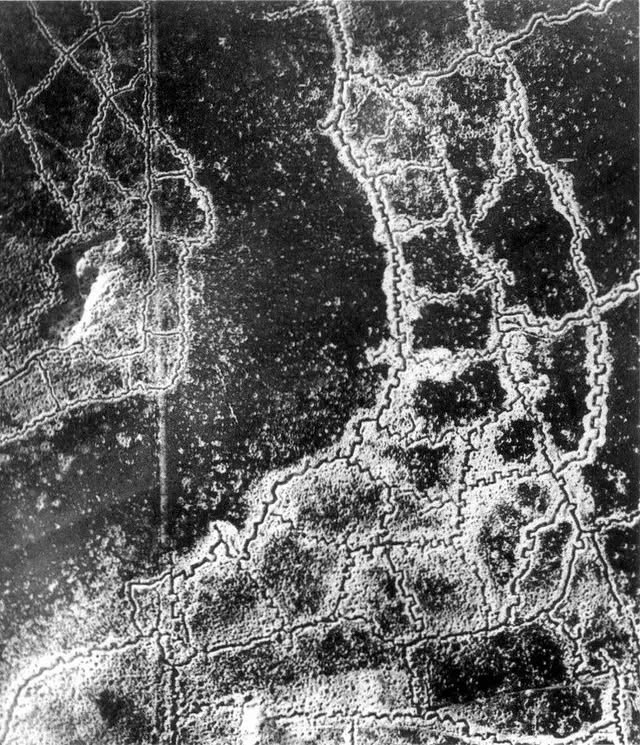

Throughout October and November 1917, the battalion was primarily engaged in rebuilding and strengthening the front-line trenches. The trenches in this sector were old, prone to collapse, and heavily damaged by bombardment. Pioneers were required to work in exposed positions, often within rifle range of the German front lines. They were also deeply involved in repairing communication trenches and deepening dugouts. With winter approaching, drainage systems had to be rebuilt to prevent the trenches from flooding. Below is a picture of a typical Pioneer Regiment at work in Ypres, September 1917.

The sector was low-lying and notoriously boggy. Stable walkways were essential to move men, supplies, and stretcher cases, so they would have been deployed by laying down duckboards and improving access routes. As artillery fire intensified, communications had to be protected by burying cables deeper, another task done under constant threat of shelling. This was a vital but extremely dangerous job.

William’s Final Days

The Battle of Cambrai had begun just one day before William died, on 20 November 1917. Although the 16th (Irish) Division was not directly involved in the opening assault at Cambrai, the entire British front was in a heightened state of tension. German forces were keenly aware that major British operations were underway and were shelling neighbouring sectors violently to disrupt movement and prevent reinforcements. The 16th (Irish) Division recorded heavy shelling in its sector. War diaries for divisions in this area consistently note:

- Journeys to work sites shelled by German 5.9-inch guns

- Pioneer working parties sustaining casualties while repairing trenches

- Daytime movement becoming extremely dangerous due to observed fire

- Night-working parties targeted with machine guns and trench mortars.

Because the battalion was not involved in any planned offensive or raid on 21 November, the most likely cause of William’s death was enemy shellfire while working in or moving to the front-line or support trenches.

Where Exactly Were They Working?

Although the exact trench map reference is not recorded for every soldier, the 11th Hampshire Pioneers were with the 16th (Irish) Division in the Hulluch–Bully-Grenay–Loos sector, north of the Lens coalfields. This was a landscape dominated by colliery slag heaps, shattered mining villages, chalky, unstable ground and shell-torn trench lines dating back to 1915

The frontline here was extremely close; in many places, British and German trenches were 150–250 yards apart. It was a place where a single shell could kill several men in an instant.

The Area Where William Died (21 November 1917)

(This map shows the Loos–Lens–Hulluch sector where the 11th Hampshire Regiment’s Pioneer Battalion served in November 1917.)

The map above shows an aerial view of the WWI Loos-Hulluch trench system in France between British trenches (left) and German trenches (right). In the middle of the two is no man’s land.

William is laid to rest at Bucquoy Road Cemetery (Ficheux), just outside of the beautiful French town of Arras. In the summer of 2025, I travelled across the battlefields of the Western Front to honour three members of my extended family who gave their lives in the First World War. The journey was profoundly moving, walking among endless rows of white headstones, each marking a life ended too soon and a family left with an irreplaceable loss.

As I visited each cemetery, I made a personal vow. At every resting place, I would select one soldier, someone unknown to me, someone with no connection to my family, and I would research them and share their story. This is the third and final story in that promise, dedicated to William Richards Crump. It is my way of helping ensure that his name, too, is remembered.

(Image from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

A Family Changed Forever

The most heartbreaking part of William’s story is not found in military records but in the quiet aftermath that followed. When William was killed on 21 November 1917, his wife Ann was more than eight months pregnant. Just five weeks later, she gave birth to their second son, James Henry Crump, a child who would never know his father. Ann was left a widow at 23, raising two small boys on a modest war pension. The loss must have echoed through the family for decades, shaping the lives of children and grandchildren who grew up knowing only the name of their father who never returned. His name is forever recorded amongst the hundreds of thousands of other names lost in print.

A Closing Tribute

Private William Richards Crump is one of the thousands whose individual stories risk being swallowed by the enormity of the First World War. Yet his life is marked by hardship, duty, brief happiness, and deep sacrifice and deserves to be remembered.

He was a son who grew up without a father’s name.

A husband who married on the eve of a world conflict.

A young father who left home to serve, believing he would return.

A soldier who worked in the most dangerous conditions the Western Front could offer.

And a man who died not in a great charge or a named battle, but in the quiet, relentless grind of daily wartime labour.

His legacy lives on not only in the family he never saw grow, but in the continuing act of remembrance. In telling his story, you ensure that William is not forgotten and not just a name carved in stone, but a life lived, a family loved, and a sacrifice made.

(Image from my collection, taken during my WW1 battlefield visit in July 2025)

A soldier dies twice: once in battle, and once when he is forgotten.

Why not visit my new website:

All My Blogs For Family Tree Magazine in one handy place

Copyright © 2025 Paul Chiddicks | All rights reserved

These are such wonderful stories and I hope a member or members of his family connect with them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Sheree that means a lot

LikeLiked by 1 person

😎

LikeLike

A sad loss for this young man’s wife and two sons. I hadn’t heard of the Pioneer soldier role before. Thank you for sharing the story of this soldier’s life, from birth to the war that ended his life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for stopping by and reading his story Marian

LikeLike

I hope that a member of this family finds your thoughtful tribute one day. Currently we are watching Ken Burn’s American Revolution series and no matter what the War the cost is dear. I also happen to be reading a novel by Lars Mytting called ” The Sixteen Trees of the Somme”

The wars circling the globe and leaving a shredded mass of death in their wakes, suggest we have learned very little. Very sad. But your storytelling is a reminder of the True cost of War. (My grandfather served in France in WWI https://wheatonwood.com/2021/03/25/the-inherited-object-revisited/)Had my grandfather not survived I would not be here. Well done!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Kelly, i live in hope that one day a family member might get in touch and even share some images of him. You just never know. Thank you for also sharing the link to your blog about your Grandfather’s amazing WW1 book. What an amazing find all from your grandfathers book. You are so fortunate to have so many wonderful family heirlooms in your collection and even more special when you know the significance of their meaning.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You might enjoy the novel mentioned above. Set in France, Norway and the Shetlands.

LikeLike

As I have also commented elsewhere, this is a compelling read and such a lovely tribute to William

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Jane that means a lot

LikeLike

Well done. I also hope that his family comes across this post and perhaps, like the rest of us, once again, realize what those who came before us sacrificed.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you I can live in hope, but at least his story has been told now.

LikeLike